- July 11, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

By Adrian Moore and Spence Purnell

Sarasota County Commissioners have decided one of their priorities for 2017 is re-examining county programs intended to stimulate job growth. Under particular scrutiny is the county’s use of tax incentives to lure new businesses into the county.

That program erupted into local controversy last year over “Project Mulligan” a large package of tax cuts offered to entice the headquarters of North American Roofing to move to Sarasota County. Not surprisingly, local roofing companies wondered why county leaders would make a deal for a new competitor to pay less taxes than do long-standing Sarasota County roofing companies.

North American Roofing chose to go to Tampa, but the controversy raised by Project Mulligan remains, exposing two key problems of the county economic development tax incentive program.

The first is that the program is inherently unfair. Companies that already exist see their tax money going to make possible tax cuts for new competition. Companies that are located in Sarasota County because it is a good place to do business see their tax money going to make possible tax cuts for new competition. It is a process by which the county government picks winners, a few from among the many, to get special treatment and pay less in taxes.

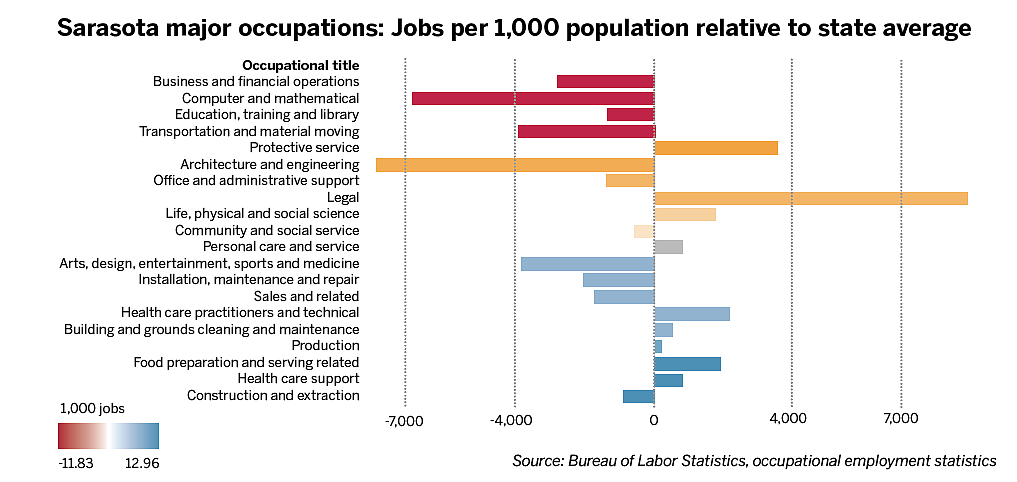

That is not just unfair, it is arbitrary. The accompanying chart shows what major occupational categories Sarasota has more or less jobs in compared to the state average: those categories with bars in the negative are where Sarasota has fewer jobs per 1000 people than the state average. But figuring out from this information what jobs Sarasota “needs” that the county government should try to subsidize is virtually impossible. Hundreds of market factors and many, many policy decisions feed into why some jobs tend to occur in greater numbers in Sarasota, and some in fewer numbers. A decentralized market process driven by consumer demand can take all those factors into account. A few people sitting in the county building looking at applications for tax breaks cannot.

Second, tax incentives are an ineffective way to create jobs. Optimizing the location of a firm entails finding the place that has the right demographics and trends both for your customers and your workforce, the right kind of workers with the right skills, attractive and affordable homes for workers and management you bring with you, accessibility in the transportation network to your supplies and your customers and your shipping hubs, a favorable competitive landscape where synergies with complementary companies are possible, and where local policies are favorable to success.

Tax incentives are but one part of the last of those factors. A company that chooses where to locate based which local government will pay it the biggest bribe in the form of tax cuts is not a company working toward long-term success. It may leave if offered a larger tax incentive bribe elsewhere and meanwhile will not likely create jobs at the rate of companies that properly chose Sarasota County because it is overall best for the success of their businesses.

Florida’s legislative leadership has killed the state tax incentive program for exactly these reasons: it has unfairly benefitted some business that move to the state at a cost to businesses already here, and all too often the companies given tax incentive bribes haven’t created the jobs they promised they would.

This year, Orlando ranked third in the nation for job growth among U.S. cities. Little if any of that growth can be attributed to tax incentives. Forbes magazine’s analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics data on job growth that named Orlando third found that:

Orlando’s resurgence has been driven by growth in professional business service jobs (up 26.8% since 2010), construction-related employment (up 11.5%) and by its largest sector, hospitality, up 22%. The metro area’s population has exploded from 1.2 million in 1990 to 2.3 million today. Much of this recent growth has come from domestic migration, which has accelerated two and half fold since the end of the recession. This has fueled a modest resurgence in construction employment, which expanded 4.6% in the last year…

Sarasota County should follow the state’s lead and not use economic development tax incentives. Instead commissioners should focus on the basics that lead to a thriving local economy—some of which are obvious, like good schools and low crime. Others are maybe not so obvious.

For example, as I wrote in January, housing supply and transportation are key, and Sarasota County could do more. Local laws that artificially restrict the housing supply, particularly of apartments, condos and rentals, and raise the cost of living near downtown areas restrict workforce accessibility crucial to the success of startups or businesses moving into the area. Millennials are the future workforce, and Sarasota must allow the kind of growth in housing and the types of projects that accommodate millennial working and living habits. As well, congestion and lack of mobility strangle economic growth, hurt business and repel a talented potential workforce. The transportation network must keep up with growth, must be operated for improved flow of traffic, and must provide reasonable travel times throughout the metro areas.

Notably, most job growth comes not from new businesses moving in, or from growth of existing businesses. It comes from new startups. Creating the conditions that foster an economy of entrepreneurs and startups is the engine of economic growth. That means keeping regulatory costs like licensing fees, siting permits and marketing restrictions down, having efficient and expeditious permitting offices that help, rather than hinder new business.

The county can take positive steps to encourage startups. “Innovation districts” are specially approved districts near downtown areas that allow for and create conditions amenable to encourage high concentrations of educational institutions, residential development, public space, entrepreneurs and local business. Our knowledge-driven economy has shifted productivity to innovation — meaning the combination of knowledge and capital produces more firms. Districts that integrate innovators and services that help build knowledge and mentor entrepreneurs.

Since growth, traffic congestion and economic development are all on county leaders’ issue priority lists, there are some great overlaps here. Rather than trying to bribe new companies to locate here, the county has an opportunity to focus on policies that allow for housing supply to meet demand, invest in adequate transportation infrastructure and operations, and foster a culture of innovation and startups. And in doing so they can help create the conditions for improved job growth emerging from market decisions, rather than county government picking winners.

Adrian Moore is vice president of Reason Foundation and lives in Sarasota. Spence Purnell is a policy analyst at Reason Foundation and lives in Bradenton.