- April 7, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

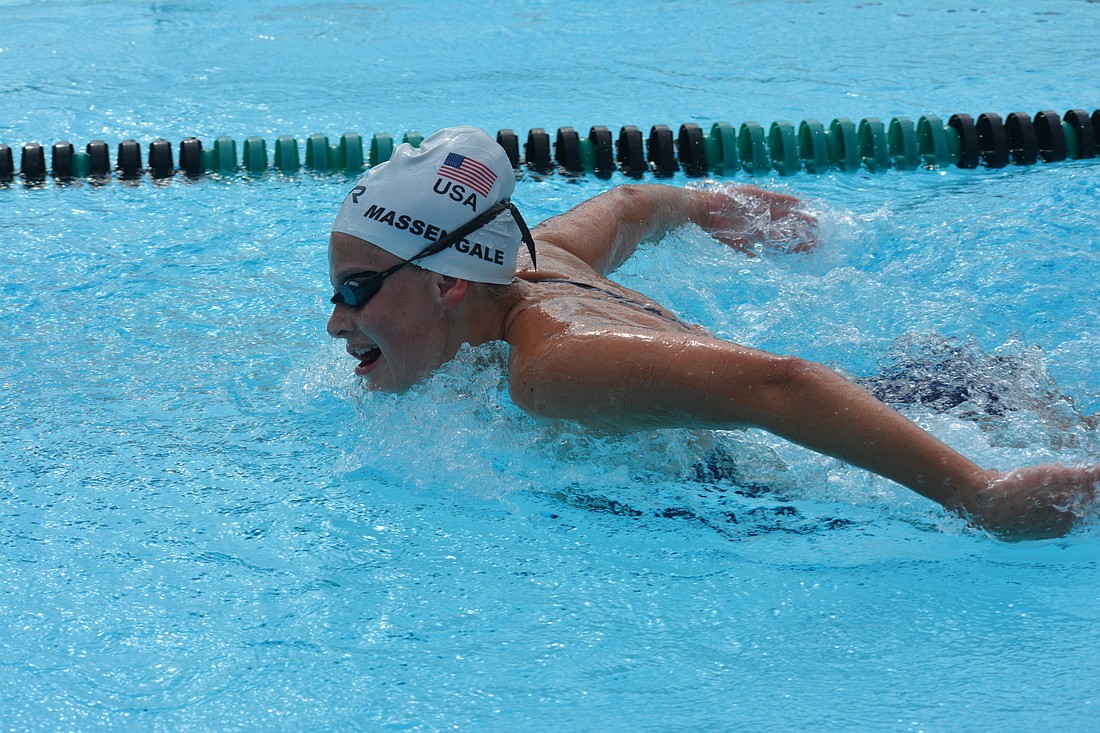

As swimmer Emily Massengale explodes from the starting block, she hears nothing.

No starting buzzers. No chatter of the crowd. No splash.

The Lakewood Ranch High sophomore is used to it. Her hearing loss began before her first birthday, likely due to a severe fever. At 14 months old, she was declared “profoundly deaf,” which means she can’t hear any noise below 90 decibels, or roughly the sound level of a jet airliner, according to her mother, Rene Massengale.

She has received two cochlear hearing implants to combat the damage, but there’s only so much that can be done. With the implants, Massengale can hear people emit noise, but still has difficulty translating that noise into words. She’s learned to read lips and has become adept at holding a conversation.

Massengale and her family moved to Lakewood Ranch two weeks ago. They chose the area because it’s where she felt the most comfortable with the coaching staff and team. They had visited with Mustangs coach Julie Santiago before the move, and knew she was willing to work with their daughter to break down any barriers in communication.

If her track record is any indication, she’ll fit in just fine.

In July, Massengale was selected by USA Deaf Swimming to represent her country in the 2017 Deaflympics in Samsun, Turkey. She previously competed in the 2015 World Deaf Swimming Championships, but those were held in San Antonio, Texas. This was her first time out of the country, as it was for many of her teammates. The bonding with her teammates was the first of many special moments for Massengale on the trip.

Finally, she was with people who understood her plight, she said. Her teammates at the Deaflympics understood the frustration of having to read lips, and of having people talk loudly and with elongated syllables because they think they won’t be understood otherwise.

“It was an emotional experience, as a mother, to see them connect that way,” Rene Massengale said. “It was overwhelming, and heartwarming to see just how she’s overcome this disability.”

The emotions were just beginning.

Massengale, who can’t wear the external part of her hearing implants in the water, finished third in the 400-meter individual medley, an event in which she didn’t expect to be a medal contender. Her finals time (5:13.66) was 18 seconds faster than her previous best. When her eyes met her time on the scoreboard, she let out a piercing scream of elation and slapped the surface of the water.

On the medal stand, tears formed in her eyes. This was the product of years of hard work, years of fighting the idea that her hearing loss would hold her back.

She wasn’t done. Massengale set the all-time American deaf record in both the 50- (31.66) and 100- (1:07.16) meter backstroke, though she didn’t medal in either event. On the final day of the Deaflympics, Massengale was exhausted and fighting a fever and cough. She still had one event, the 200 backstroke, and was determined to finish strong. She took to the pool, and delivered a sterling performance, finishing in 2:27.06, winning another bronze medal.

“The next one (Deaflympics) is in four years,” she said. “I know I can do much better. I know I’ll get even more medals next time.”

Massengale has a bright future in the sport, and it’s a goal of hers to swim in college, but that’s not where the vision of her future ends. She eventually wants to become a swim coach so she can help others, like her coaches, new and old, have helped her.

“Don’t stop what you love just because you can’t hear, or can’t see, or something else,” Massengale said. “I want to encourage people to keep going.”