- December 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

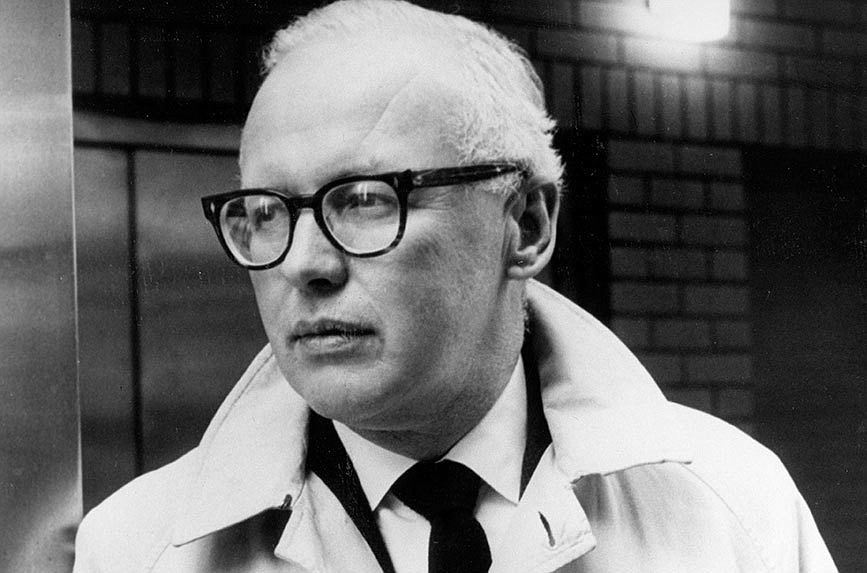

If John D. MacDonald had lived to be 100, last Sunday would’ve been his birthday. For most of his career, the novelist lived and wrote in Sarasota. The city recently celebrated his birthday and put up a plaque in his honor. It was long overdue. He did more than tell great stories; he reinvented his brand of storytelling.

In the beginning, there was the author John D. MacDonald. Before Tony Montana and his little friend, before the pastel-wearing private eyes of “Miami Vice,” before the eco-warriors of Carl Hiaasen, before the troubled waters of Randy Wayne White, he got there first.

We refer, of course, to the territory of Florida crime fiction. (Which is a wordy way of saying Florida fiction, so let’s stick with that.) Getting it right is all about a sense of place. Before MacDonald came along, most writers were either out of date or just plain wrong.

Judging by books and movies, everyone who lived in Florida either ran a hotel on the beach, worked a fishing boat or sweated in the fields of a family farm.

That wasn’t MacDonald’s sense of the place. He had moved to Sarasota in 1951. He was a Floridian in the flesh — and his stories would soon follow. By the late 1950s, he’d written a slew of best-selling crime novels, including “The Executioners,” which became the basis for the “Cape Fear” movies. While some of these tales unfolded in the Sunshine State, they weren’t very sunshiny.

MacDonald’s short stories and paperback originals were in the long shadow of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler — the tradition of noir crime fiction, in print and film. The tales of this black-and-white world were usually set in L.A.

But MacDonald was dreaming of Florida — and dreaming in color. Starting with green. The color of nature and money.

His novel “A Flash of Green” came out in 1962. It was a reference to a rare sunset spectacle and a knowing tale of Florida corruption and environmental degradation.

MacDonald had a lot to say about this territory. Creating his own detective series set in Florida seemed like the perfect idea. His hero would be a knight in “rusted armor” named Travis McGee. Where Sherlock Holmes could be found at 21 Baker St., McGee’s houseboat office was docked at Slip F-18 at Bahia Mar Marina, Fort Lauderdale. No so much a literal detective, McGee was a salvage artist who recovered lost money, valuables and honor. The monochromatic tone of noir crime fiction just wasn’t right for the land of pink flamingos and neon. Why not tropical colors?

MacDonald had been thinking metaphorically. His friend, the abstract expressionist painter, Syd Solomon, suggested he think literally. Don’t simply write colorful novels. Put a color in every book title.

And that’s when the metaphorical light bulb went off, and his first Travis McGee novel came together.

“The Deep Blue Good-By” was published in 1964. That’s when the rules of Florida fiction changed, along with the standard cast of characters. Say goodbye to farmers, hoteliers and fishermen. Say hello to:

Drug lords and the small-town politicians they buy. (“The Green Ripper.”)

Sociopathic religious charlatans. (“The Green Ripper.”)

Corrupt southern sheriffs (“The Long Lavender Look.”)

Sure, we’d seen these characters before. But never so well drawn. Or so urban.

Before MacDonald, fictional Florida had been a scruffy frontier place. The hotel in Maxwell Anderson’s “Key Largo” was an outpost on civilization’s edge. Drive past that edge, and you might meet the Crackers of Lois Lensky’s “The Strawberry Girl” and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ “Cross Creek.” Drive further, and you could join Citizen Kane for a party in the Everglades — a wilderness that could double for the darkest corner of Africa in a Tarzan movie.

But that wasn’t MacDonald’s Florida.

The Sunshine State had a population of 5.78 million in the year his first Travis McGee novel came out. Ft. Lauderdale and Miami were big cities. Sarasota was a sophisticated small city, with a population that climbed from 34,083 in 1960 to 40,237 in 1970. Unspoiled? Relatively. Unsophisticated? Never.

MacDonald might have known a few farmers, hoteliers and fisherman. But he also knew world-class visual artists like Syd Solomon; the groundbreaking architect Tim Seibert (who designed his new house on Siesta Key in 1970); and MacKinlay Kantor, Joseph Hayes and the other heavy-hitting novelists of The Liars Club, who met every Friday at The Plaza Spanish Restaurant on First Street.

Sarasota was an artists’ colony back then. A Venn diagram of the writers, artists and architects of the 1960s would be complicated, indeed. The groups overlapped and intermingled — especially on Siesta Key.

Its island lifestyle combines bohemian independence and urban sophistication!

That’s what an ad might tell you today. In MacDonald’s glory days, it was still true.

The cosmopolitan melting pot of Sarasota and South Florida informed the world of Travis McGee. McGee was no lone wolf. His fictional friends reflected MacDonald’s real-life network.

The world of noir crime fiction can be bleak and grim, and MacDonald’s Technicolor landscape saw its share of tragedy. Good things happened to good people, and not all wrongs were righted. But that world, like its creator, had a sense of humor. McGee’s mode of transportation, as imagined by MacDonald, was a Rolls Royce converted to a pickup truck.

But when it came to environmental issues, MacDonald was deadly serious. His 1977 “Condominium” took place on a thinly disguised Siesta Key. The titular condo's boomerang-shaped plans came from Tim Seibert. After blocking the developer’s scheme to build it near his Big Pass home, MacDonald graciously put it in his novel.

The fictional builder was a mobster who skimped on materials and pocketed the difference. The fictional condo was a house built on sand. It took one good storm surge from a hurricane to wash the thing away. Too bad McGee wasn’t around to break up the hurricane party.

In the colorful world of John D. MacDonald, nature is an assault victim, and Florida is one big crime scene. His long list of authorial admirers agree — including Carl Hiaasen, Elmore Leonard, Tim Dorsey and Randy Wayne White.

They’ve been examining the evidence ever since.