- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

If your car ride home from the theater involves an argument, John Strand has done his job.

No, the Washington, D.C. -based playwright isn’t set on tearing apart your relationship — quite the opposite. He wants to use differences of opinion for the greater good. It’s a call for a return to civil discourse.

Disagreements don’t have to be a bad thing. In fact, Strand argues in “The Originalist,” running Jan. 18 through March 7 at Asolo Repertory Theatre, they’re crucial for personal, professional — and democratic — growth.

And focusing on one of the most polarizing figures in recent political history, the play leaves audiences with plenty to disagree about.

The play, which premiered in 2015 in Washington, D.C., uses the late Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia as its central figure in making its case.

“Working in D.C., one thing that came to bother me was the idea of the disappearing political middle,” says Strand. “I’m troubled by our political discourse. We’ve come to a point where we focus on individuals rather than policies, and all we do is dismiss the person with the opposite opinion. That’s the best we can do after 240 years?”

It was a theme Strand wanted to explore onstage. But first, he needed a strong central character to embody the issue.

Enter Scalia. The late Supreme Court associate justice served for nearly 30 years, earning a reputation as a staunch, outspoken constitutional originalist — and bullishly conservative.

To some, he was an intellectual beacon for conservative values. To others, he represented antiquated ideologies and a threat to civil rights. There weren’t a lot of lukewarm opinions on the man.

“He was just a lightning rod for controversy,” says Strand. “Who better to put center stage? Immediately, half the audience views him as a villain. It’s remarkable that one person could inspire this kind of hatred. I was interested in asking, ‘How was he the villain? How wasn’t he?’”

Polarization aside, Scalia was nothing if not willing to hear opposing views. In fact, he reveled in it. The play follows Scalia and his legal clerk Cat — a black, liberal woman in her early 20s.

The two couldn’t be more opposed in their political views. But their conversations and arguments, sourced from interviews with former Scalia clerks, illustrate the type of discourse Strand says is disappearing.

“Early in the play, he interviews her,” says Strand. “They’re complete political polar opposites. They go back and forth, and things get heated. You think he might dismiss her, but he says, ‘You’ll be more than my law clerk. You’ll be my sparring partner.’ He invites her to bring him her ridiculous liberal positions, and he will break them down one by one.”

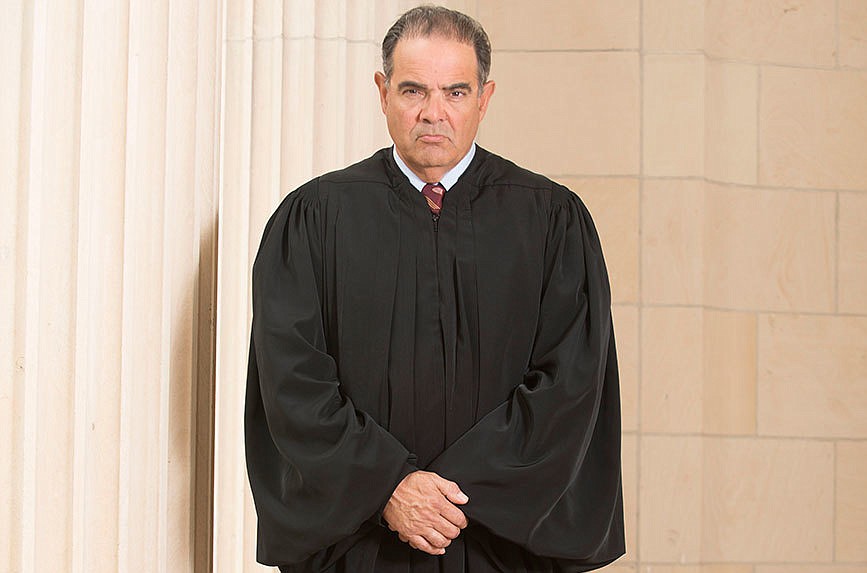

Edward Gero, who plays Scalia with an uncanny resemblance (some publications mistakenly published his photo in obituaries after Scalia’s death), had the opportunity to meet and form a friendship with the late associate justice, who told him right off the bat — “I won’t be seeing the play. But I’m glad they got somebody good to do it, so I won’t be embarrassed.”

"If we can’t have intellectual discussions, I’m not confident we’ll survive."

- John Strand, playwright, 'The Originalist'

To prepare for the role, Gero observed Scalia in court and read biographies about him, as well as his dissents and decisions.

“There are definitely Scalia-isms,” says Gero. “He has some very signature mannerisms, but more than that, he was a great orator. He was a showman; he knew how to drive to the end of a line; he had comedic timing, and he had a mastery of the English language. He could roll off these long, complex sentences without any hesitation. It was humbling.”

Perhaps most importantly, Gero says he was struck by Scalia’s eagerness to engage with those who disagreed with him.

“He had an affection for those people,” he says. “He loved a strong argument. It was never personal. The main message is that this is how this experiment we call democracy works at its best — discourse. The trap is to vilify people on the other side.”

Strand says the Asolo Rep production is in many ways a second premiere. With Scalia’s death in 2016, and the tumultuous recent election cycle, the play has taken on renewed significance for Strand, who says its message is more important than ever.

“People are unable to even talk to each other,” says Strand. “There’s so much vitriol. If we can’t have intellectual discussions in which we disagree, I’m not optimistic we’ll survive.”

So, as unusual as it might sound, Strand hopes people will leave his play arguing. And continue to do so.

“One of my favorite things is hearing people tell me they argued about the play after it was over, even weeks later. As a playwright, what more could you want? You can’t grow if you only surround yourself with people who agree with you. So I hope people keep discussing. You might just discover something about yourself worth knowing.”