- December 14, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Four galleries, four exhibitions — Art Center Sarasota has the space to present more than an eyeful under one roof, and it knows how to use it.

If you like to really study artwork, to analyze and appreciate artists’ imagination and execution, and if encountering variety as you move from piece to piece brings that tendency out in you even more, be advised, you’d better set aside a few hours for this set of exhibitions.

In the large gallery in the back is a juried exhibition called “Eye Candy.” The call to artists said it was open to all media, all subjects, and that’s a fair description of the 157 pieces on display.

In the middle gallery is “Black Muse 2020,” the annual exhibition of members of the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History. It’s a heartfelt collection filled with images that depict an African American perspective on life in times of struggle and in everyday living.

It could take you a while to reach either of those exhibitions, though, because the two galleries at the front might be hard to tear yourself away from. The exhibitions are independent of each other, but they are on similar wavelengths. Not surprisingly, the two artists are colleagues and friends. Ryan Buyssens and Kim Anderson are art professors at New College of Florida. Both of their exhibitions combine the modern with the old-fashioned in a way that is innovative and playfully interactive.

Buyssens’ exhibition is called “interplay.” The one-word title is aptly descriptive. Nothing stands still for long in this exhibition, neither the people nor the art.

“I like to say my art is rooted in the fourth dimension: time,” Buyssens says. “I like to compose in time. I like colors, I like materials, but I also like how things can change.

“So all my work has that ability to somehow move or change. And some of it more recently, I’ve been learning how to make it interactive where the viewer is actually part of the art because they make the change.”

Whether he meant to or not, Buyssens’ exhibition appears to reflect change on a wider scale.

Some of the pieces look futuristic. One wall installation consists of lamps pointed toward small, slowly rotating glass panes, causing a constantly swirling multicolored reflection on the wall.

On the opposite wall is an installation that can best be described as three robot seagulls. When a viewer gets within a certain range, proximity sensors activate the birds’ wings to flap.

Among them are pieces that look like they’re out of the late 19th century, including tabletop carousels with figures that, when in motion, are reminiscent of images produced by zoetropes, spinning devices from the primordial stage of motion picture technology. In an anachronistic touch, viewers make the carousels spin by pressing wooden buttons or pumping a foot pedal.

A few of Buyssens’ pieces stand outside the temporal dichotomy. Placed in a prominent spot, a black, square canvas reads “Outlook good.” But if the viewer stands a few feet in front of the painting for more than a few seconds, the words “not so” appear in the middle of the phrase.

“That’s an interactive painting,” Buyssens says. “It has, as I call it, magic built into it.”

This magician is happy to divulge the secret. He’s been mixing his own heat-sensitive paint, which reacts to the body heat of the viewer.

Not every piece is dependent on human interaction. In one corner of the room, there is a glittering skull covered with multicolored plastic gemstones. It’s an attention-grabber, in a Day of the Dead-meets-Elton John kind of way, but it’s a piece in need of an explanation. Buyssens has one.

In 2007, English artist Damien Hirst created “For the Love of God,” a platinum cast of a human skull, completely encrusted with diamonds — and with the actual teeth out of the skull from which the cast was made. It cost an estimated $14 million to make, Buyssens says.

Buyssens’ skull is his answer to Hirst. “I covered it with $14 worth of sticky gemstones and call it ‘For the Love of Gaud.’”

Near the skull is an installation with what looks like a Phillips screw about as wide as a baseball bat “screwed” into the wall. Hanging from it is a delicate chain and a sign smaller than 3 inches across that reads “Home Sweet Home.”

“I call that one ‘Domestic Bliss,’” Buyssens says. And the meaning behind that one? It’s just for a laugh, he says.

Anderson’s exhibition, called “Incandescence,” feels in sync with Buyssens’ elements that infuse the antiquated with fresh perspective. The exhibition utilizes that staple of 19th century parlors, the stereoscope.

Used mostly for entertainment, the stereoscope is the original 3D viewer, making two 2D images appear to be a single image with depth. It’s all a matter of adjusting the view to perceive the depth.

The same can be said of Anderson’s exhibition, which, like Buyssens’, can be interpreted in a big-picture sense or from a closer perspective.

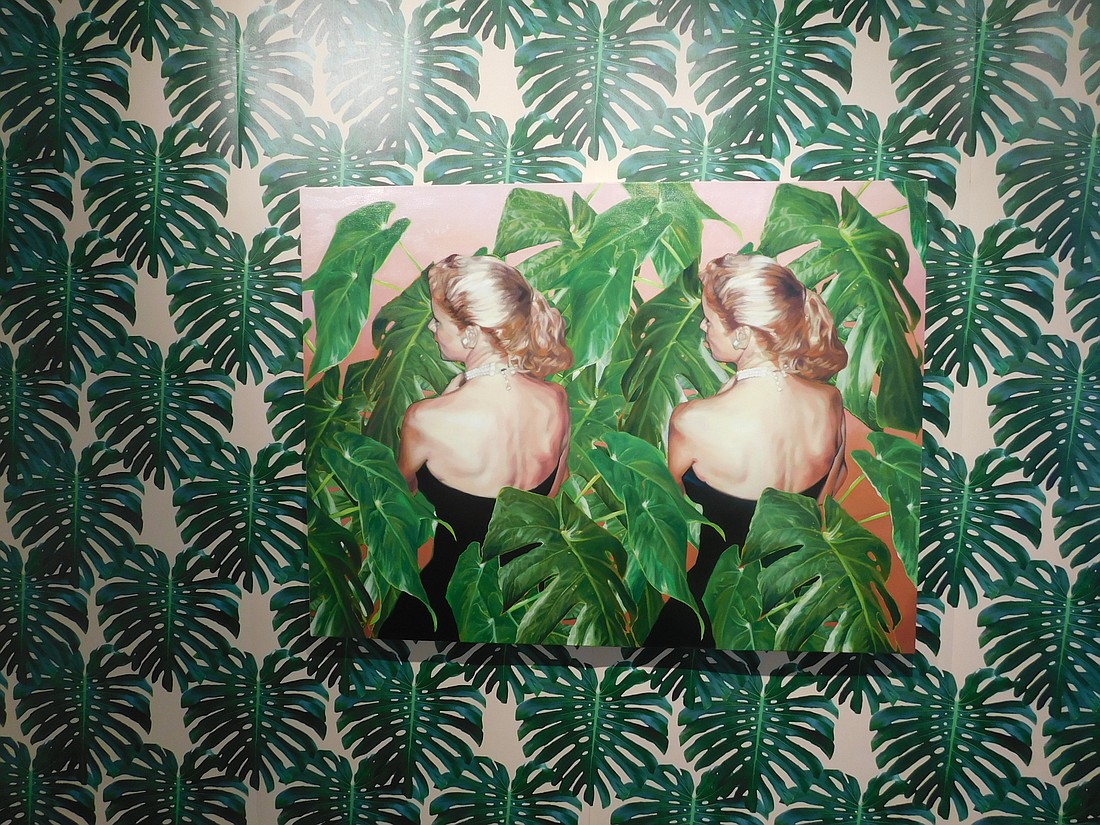

On the one hand, there is the artwork itself. Anderson has painted several paired images. They’re done in a near-photorealistic style. “I’ve always been sort of interested in the impact of photography on painting, the relationship that we’ve developed out of that,” Anderson says.

Most of her paintings are based on old Kodachrome slides. She realized that there is something visually compelling about taking the stereoscope double images, something most everyone is familiar with, and presenting them as large paintings.

“I decided I liked the idea of them being painted on one canvas because when you look at them without the viewer, it creates this double image effect that’s a little disorienting and kind of interesting,” she says. A lot of people have told her they like the images just like that, without using a viewer.

But until they use the viewer, they’re only getting half the picture. For the exhibition, Anderson hand-built stereoscope viewers. “You can find inexpensive cardboard viewers online,” she says, but she felt the boxy, wooden, 19th century style viewers added to the experience.

From stereoscopes to smartphones, Anderson says, we have a history of using devices to view the world. The devices become commodified, “and then there becomes this sort of social interaction and engagement.”

On opening night, Anderson anonymously stood back and watched as the people worked together to find just the right distance to view each painting. “To me, that in a way becomes a part of the artwork, that interaction that the audience is having,” she says.

Gallery openings can be stiff, intimidating affairs, Anderson says. But when you can provide some kind of interactive feature, add a simple puzzle to the experience, make it like a game, like getting the stereoscopes to work, then people start to see art in a whole different way.