- May 3, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Jim Stowell’s “The Things They Carried” is now on patrol at FST’s Stage III. His play is a taut adaption of Tim O’Brien’s short stories about a platoon of American soldiers fighting in Vietnam. It’s fiction based on fact. A writer named “Tim O’Brien” was the book’s central character; the book’s real-life author served in the 23rd Infantry Division.

How do you fit the Vietnam War on a tiny cabaret stage? You don’t. This FST production doesn’t even try.

Don’t expect the theatrical equivalent of a larger-than-life movie like “Platoon” or “Full Metal Jacket.” Stowell’s one-man play stays close to its literary source. It’s a first-person narrative, eloquent and introspective. This isn’t the big picture. It’s a glimpse of the war inside someone’s head.

Like the stories that inspired it, “The Things They Carried” wears its central metaphor on its sleeve. It’s all about the burdens of the Vietnam War experience. Those include the weight of memory, guilt and loss. But it’s also about literal burdens. And non-metaphorical weight.

Early in the play, the O’Brien character obsessively itemizes the stuff the troops have to hump around. The burden includes: “P-38 can openers, pocket knives, heat tabs, wristwatches, dog tags, mosquito repellent, chewing gum, candy, cigarettes, salt tablets, packets of Kool-Aid, lighters, matches, sewing kits, C rations, and two or three canteens of water.” There’s also a fatigue jacket, spare trousers, a steel helmet, a flak jacket, and depending on rank and personality, an illustrated New Testament, premium dope and comic books. Each grunt also schleps an all-purpose rubber poncho. It’s good for protecting you from the rain or wrapping up your remains.

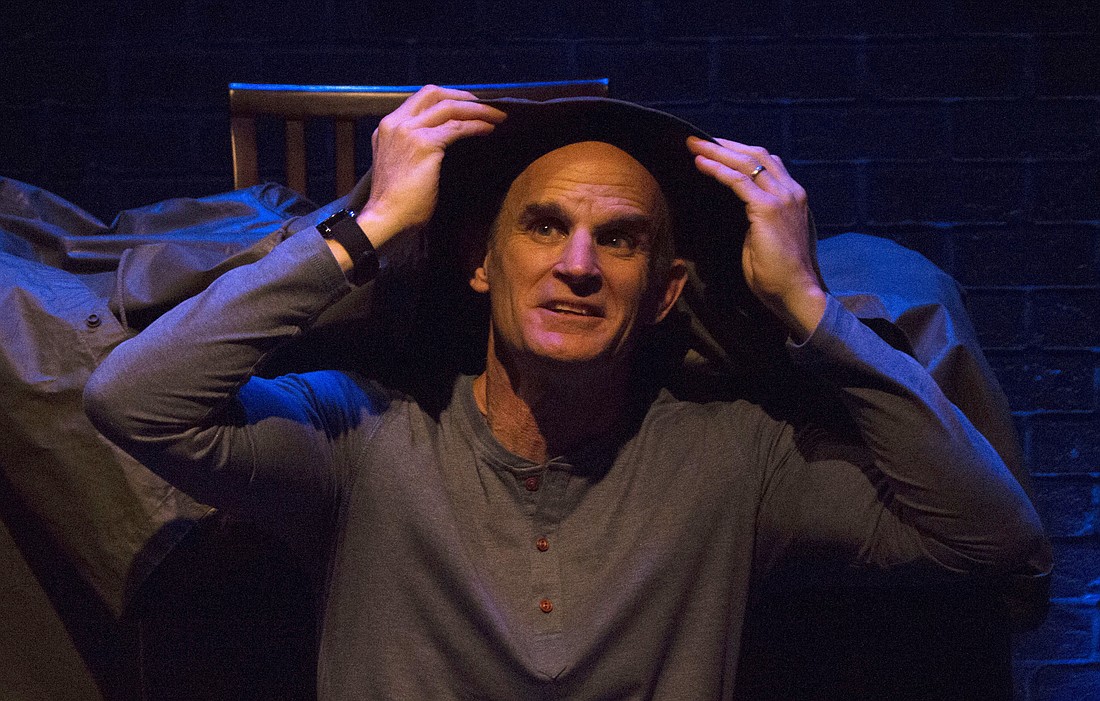

David Sitler usually stays in character as the eloquently tormented O’Brien. He’ll occasionally turn into other characters — with abrupt, brilliant shifts of voice and body language. The platoon in O’Brien’s head includes: Kiowa, his best friend and mentor, who’s a Native American and a devout Baptist; Azar, an unhinged, drug-addled, manic specimen of humanity with a sadistic sense of humor; “Rat” Kiley, a medic who goes AWOL in fantasy land; Ted Lavender, a self-medicating hippy; and Lt. Jimmy Cross, a Christ figure who blames himself for every death and burns his fiancée’s love letters so they won’t distract him.

These vivid character portraits flash like summer lightning with no glimpses of the big storm. Expect no overarching plot, just a series of vignettes, incident, accidents, close calls and horrible deaths leading up to a final epiphany. There’s also a flashback to O’Brien’s attempt to flee to Canada — and the reason he changed his mind, only 20 yards away from another life.

Director Kate Alexander takes a matter-of-fact approach to the material. “Show, don’t tell,” is the usual advice. But Stowell’s adaptation inverts that principle. A single man on stage tells you his story. His play’s a spoken-word narrative, and that’s all there is to it. Alexander honors that simplicity.

Bruce Price’s minimal set is aptly suggestive of a writer’s quiet, private space, but doesn’t overdo it. O’Brien’s words paint the scene; the furniture stays in the background where it belongs. Aside from vivid word pictures, Bryce Benson lighting and Jon Baker’s sound design do the heavy lifting in evoking the wartime environment. You hear a bang, see a flash of light. That’s enough for your imagination to create a world. Or one-man’s war.

Sitler’s mercurial portrayal of O’Brien (and his imaginary friends) is truthful, gripping and gutsy. His character(s) is usually soft-spoken and unflappable, but takes occasional violent detours to the ragged edge. Sitler goes over the edge when the scene demands it, but never over the top. It’s a masterful, fearless performance.

The spoken words at the play’s heart flow from one of the best books on the Vietnam War (or any war) ever written. It’s right up there with Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories — the tales of a shell-shocked character, who hailed from Minnesota, just like the real-life O’Brien. (The author calls that a coincidence, and denies any Hemingway influence, aside from his hatred of adjectives.)

Like O’Brien’s original short stories, Stowell’s play has sharply defined goals. It never tries to make sense of the Vietnam War. It conveys what the war was like for one person.

For Tim O’Brien, it clearly made no sense all.