- May 3, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

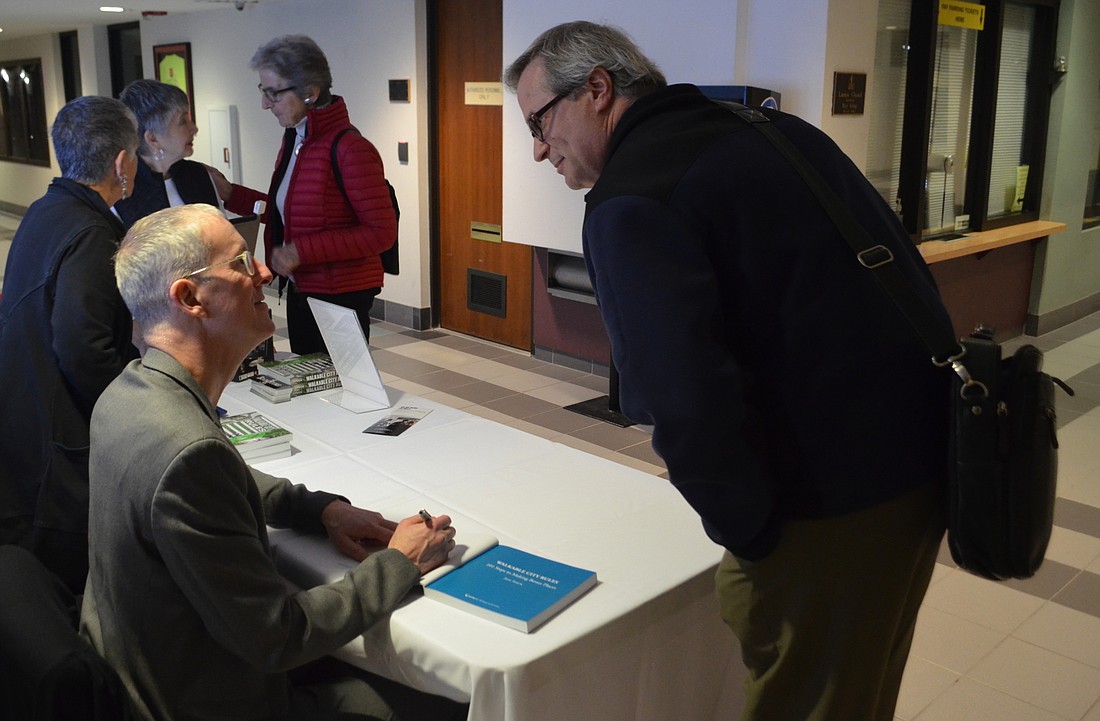

Jeff Speck wrote the book on walkability. (Correction: two books, as of last October.)

And, according to him, Sarasota is on the right path to creating an urban center that residents and visitors can get around on foot.

“You could become an incredibly more vibrant and walkable city by keeping on doing what you’re doing in the areas that surround the downtown,” Speck said. “You’re already there. You can really take it to the next level very easily.”

Speck came to Sarasota on Thursday to deliver a lecture on walkability at City Hall, an event co-sponsored by the city, the Downtown Improvement District and ten other groups, businesses and individuals. Ahead of the evening presentation, Speck went on a tour of downtown and the Rosemary District alongside city staff.

That tour — along with Speck’s previous visits to the city, which included work on Duany Plater-Zyberk’s 2001 downtown master plan — generated some specific commentary on Sarasota’s walkability strengths and weaknesses during the lecture. Although Speck complimented the growth the city has shown, he also highlighted areas for improvement.

Speck’s 2011 book, “Walkable City,” outlines his “general theory of walkability:” To get people to walk, that walk “must be useful, safe, comfortable and interesting.” Speck’s lecture Thursday was built around the different components of that theory, outlining ways cities succeed and fail at creating the conditions that are most effective for generating more pedestrian activity.

He devoted the most time to one of those components: safety. Sarasota residents advocating for a more walkable city have raised concerns about pedestrian safety, a conversation that has included a push for wider sidewalks and increased building setbacks.

Speck, however, said sidewalk width is less important than several other factors in creating a safe pedestrian experience. Much more significant, he said, is road design.

He said traffic engineers typically design streets to primarily serve automobiles. In the past, that’s meant making roads more “forgiving” for cars in the name of safety. Cities built wider lanes to make drivers more comfortable and restricted the placement of trees on the street, fearing motorists could crash into them.

Speck called that logic backwards. In an urban setting, he said friction has the effect of slowing drivers down, which creates safer streets. Creating narrower lanes, planting trees and adding bike lanes are ways to get drivers to pay more attention to their surroundings and comply with the desired speed limits.

“Anything you do to make the environment more forgiving for motorists actually has the outcome of making the speeds higher,” Speck said.

Speck said a 10-foot-wide driving lane is sufficient for urban settings. He criticized standards in Sarasota’s Engineering Design Criteria Manual, which in some areas call for lanes that effectively occupy 13.5 feet of the street. Speck recommended reclaiming that space and using it to enhance the pedestrian or cyclist experience.

“The fact is: If these are your documents and they’re on your books, then they’re enforcing dangerous design,” Speck said.

Because complaints about traffic congestion are frequent in most cities, officials often look for ways to eliminate congestion. But efforts to add more lanes to roadways and increase capacity are almost always fruitless, Speck said, thanks to a phenomenon called induced demand.

In short: Building a wider road makes driving more appealing, which increases the number of cars on the road. Eventually, more vehicular activity results in the same level of congestion as there was before the road was widened.

If cities accept that designing for increased car capacity will not eliminate congestion, they can feel empowered to instead design streets that serve pedestrians and cyclists in addition to automobiles.

“You should make your downtown the downtown you want it to be and understand it will be congested,” Speck said.

In addition to reducing vehicle speed, Speck said it’s important to make pedestrians feel protected from nearby traffic. Speck is a strong advocate for parking along the curb in areas where people want to walk, calling it a steel barrier guarding the sidewalk.

Another one of Speck’s leading contributors to a safe, comfortable walk: buildings that thoughtfully shape the street. Speck said humans like to feel enclosed, and buildings that create an engaging, comfortable edge make people more willing to walk.

He acknowledged some conditions in which pedestrians could feel constrained by the size of the sidewalk, highlighting Fruitville Road as a problem in his presentation. When asked about public advocacy for increased building setback requirements, though, he said pulling buildings close to the sidewalk was a good thing for walkability as long as proper design standards are in place. He questioned whether residents were actually interested in seeing structures set back farther from the street.

“If they are, that’s a suburban impulse that isn’t appropriate,” Speck said.

Speck met with city staff again today to discuss planning-related issues. Afterward, he affirmed his belief that Sarasota is well positioned to create an increasingly welcoming downtown for pedestrians.

“I got a sense of full buy-in and capacity from the staff when it came to issues of a more livable, walkable city,” Speck said.