- December 21, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

If Sarasota residents wanted to learn more about Sasaki, the planning company selected to develop a master plan for 42 city-owned acres on the bayfront, they weren’t hurting for opportunities this week.

Between Monday and Wednesday, Sasaki representatives appeared at three public meetings to discuss the bayfront planning process. Inspired by the grassroots stakeholder group Sarasota Bayfront 20:20, the city is working to create a new public district on the land surrounding the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall.

Luckily for Gina Ford and Susannah Ross, they’re eager to get to know Sarasota more intimately. The meetings were part of an introductory crash course for Ford and Ross, landscape architects who are leading Sasaki’s planning effort.

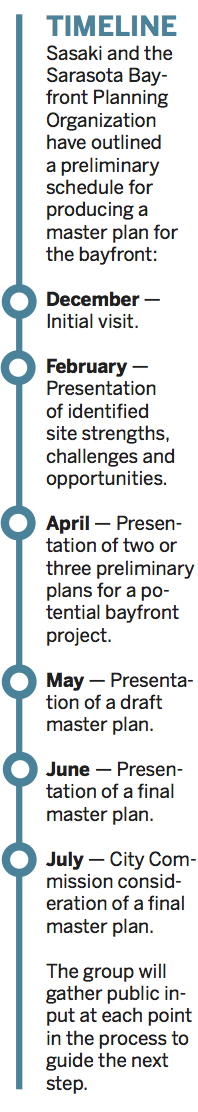

Between now and July, Ford and Ross hope to produce a comprehensive plan for the bayfront that city officials and residents will support. Working alongside the nine-member Sarasota Bayfront Planning Association, Sasaki will rely on a combination of public feedback, technical information and financial feasibility to guide its recommendations.

What does it look like in practice? Ford and Ross explained the process behind the planning to the Sarasota Observer, using examples of Sasaki’s previous work to illustrate some of the options available as Sarasota pursues a dynamic vision for its waterfront.

As the bayfront planners embark on the project, they have no parameters for the final product.

“We have a vision statement and a set of guiding principles that we think are really sound and foundational, but beyond that, we’re not coming with the idea that anything has to be any particular way,” Ford said. “Someone just said, ‘If it’s an alphabet, we’re at B or C.’”

Sarasota Bayfront 20:20’s six guiding principles for the land provide conceptual directions, such as encouraging activity throughout the day and connecting the bayfront to the rest of the city. To get from those high-level ideas to a ground-level blueprint, Ford and Ross said robust public input will inform the decision-making process.

“Oftentimes, some of our best ideas are not our own,” Ford said. “They’re things that somebody brings to a community meeting that gets us thinking in a new way about an opportunity, or makes us see something of value that we wouldn’t see as people who don’t live here.”

Right now, Sasaki is collecting conceptual ideas. During future visits, the planners will look for feedback on whether they’re headed in the right direction for Sarasota. Ultimately, Ford and Ross are focused on “getting to yes” — making sure the entire community is behind their master plan.

The conversation about how to pay for the eventual bayfront project also starts right now.

Working with a financial team, Sasaki will examine a variety of funding models, searching for one that’s congruous with the specific vision for Sarasota’s waterfront. Ford said there are hundreds of ways to pay for a project like this, but preliminary work will survey the available public and philanthropic options.

There are also opportunities to incorporate revenue-generating programming into the final project. The degree to which the project relies on that type of funding will also be guided by public input.

Already, the planners have heard a demand for lots of public open space — a “potential blue and green oasis,” as Ford described it. Those types of desires will determine the viable funding options for the final project detailed in the master plan.

“We’ve heard people really cautious about the amount of private development here,” Ford said. “That means we’ll have to think about, what are the funding sources that are aligned with public open space?”

Although a variety of stakeholders are already using the 42-acre bayfront property — and others are undoubtedly interested in a chance at moving onto some prime real estate — Sasaki isn’t as focused on the logistics of who will go where just yet.

Ford pointed out that organizations such as the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall and the Sarasota Orchestra are undertaking their own needs assessment. Sasaki will help facilitate those conversations as the master-planning group, but its directive focuses primarily on adapting the land for public use.

“Above and beyond all the other individual concerns that institutions may have, we’re looking to create the best kind of public space that we can for everybody,” Ross said.

Even if all goes according to schedule, it’ll be another seven months before the public sees a final master plan proposal. And yet, at the outset of an ambitious undertaking, Sasaki representatives are confident they’re capable of producing a transformative bayfront blueprint.

“This plan will be different from all the ones that came before it in that everyone wants it to happen,” Ross said. “Everyone.”

Sasaki planners highlighted aspects of three different projects that could be applied to the bayfront redevelopment process in Sarasota.

The project: Chicago Riverwalk

The concept: One example of Sasaki’s reliance on local input can be found along the Chicago River.

When Sasaki was planning the redevelopment of that waterfront, it found a small project undertaken by a group called the Friends of the Chicago River. The group had reproduced a small, floating wetlands in what was otherwise a dreary river — a small glimpse of the area’s ecological history.

Sasaki teamed with the Friends of the Chicago River to expand the floating wetlands. The project serves as an educational opportunity for visitors, particularly children. Ford said Sasaki strives to celebrate the environmental character of its waterfront properties even in heavily urbanized areas.

“So it’s kind of crazy what we can do here,” Ford said.

The project: The Lawn on D, Boston

The concept: Sasaki was tasked with planning a new civic district around the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center. Implementing the entire plan will take 15 years, but those involved with the project were eager to get a “quick win” to attract people to the area.

That inspired The Lawn on D, a 2.5-acre, $1.5-million activity area. Ford described it as a “temporary experimental landscape,” furnished with movable amenities including giant Jenga games and cornhole boards. The space hosted art installations and performances. Today, it’s become a permanent public fixture.

Ford and Ross can foresee a spiritually similar undertaking toward the beginning of the bayfront redevelopment.

“We know people have been waiting for a long time to see something happen on this site,” Ross said.

The project: Smale Riverfront Park, Cincinnati

The concept: Sasaki’s vision for a 32- acre park along the Ohio River came with a $120 million price tag.

To pay for it, those involved with the project developed an all-hands-on-deck financing model. To date, more than $50 million in governmental funding — from the federal, state and local level — and more than $40 million in private fund- ing have gone toward implementing the plan.

There are also revenue-generating operations on site, including bike rentals and a brewpub. Sasaki representatives said this is just one of dozens of pay- ment models available to a city embark- ing on a public redevelopment project.

“Oftentimes, it’s the more the merrier when it comes to funding,” Ford said.