- October 8, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Everyone wants to know: How soon will the economic recovery begin, and how long will it take to get back to where we were?

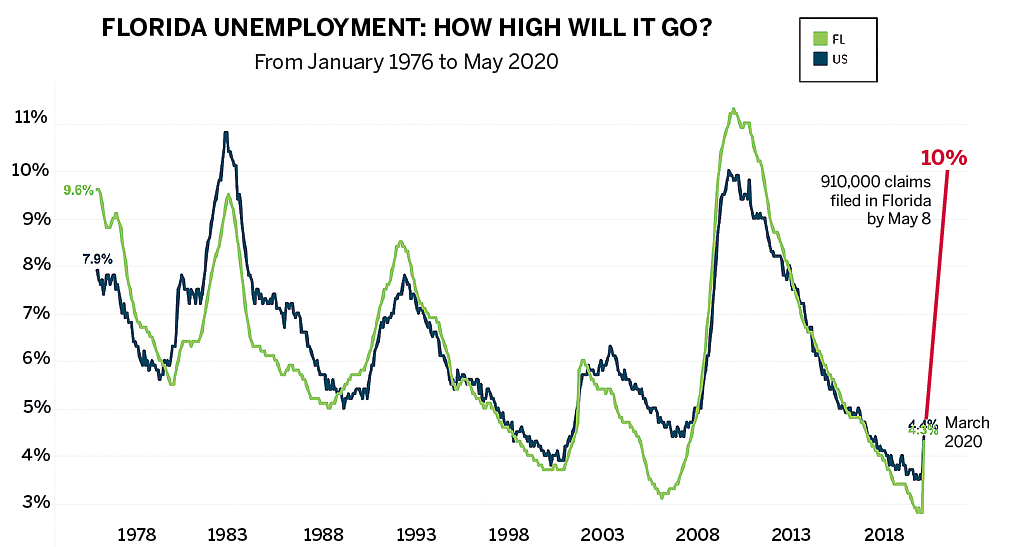

The statistics are stunning: April’s unemployment figures reported a modern record of 14.7%, a loss of 20.5 million jobs. And by the time we finish May, those numbers are expected to be higher.

A ray of light and hope is 18 million of those job losses are expected to be temporary.

Nonetheless, there are massive economic consequences of businesses closing or reducing operations, as workers and customers either voluntarily stay home or are required to by state and local policies.

Typically, economic recessions and recoveries follow a V-shaped pattern as gross domestic product falls steeply for a period then sharply turns back upward and grows just as fast. This has been the most common pattern in the U.S. over the past 50 years.

An alternative pattern is a U shape, where GDP falls steeply and gradually bottoms out and then more gradually begins to recover and climb back to previous levels. This is more likely when the damage of the economic contraction is more severe and disruptive.

Because whole industries are virtually shut down now, and many businesses won’t be able to come back the way they can from a more uniform contraction of demand and sales, some economists think this recession might well be a U-shaped one, and recovery will take longer than usual.

If there is a double dip in the economy, if, say, opening up the economy leads to a significant second wave of COVID-19 that causes a second contraction of the economy or if economic activity initially jumps but then business bankruptcies and unemployment wind up being too slow to turn around, that could drag the economy down again. A W-shaped recession.

Finally, we could see a swoosh, or check mark-shaped recession, with the sharp downturn in GDP followed by a slow and gradual recovery taking much longer than usual to return to pre-recession levels. This might be made more likely if reopening the economy is done slowly and gradually across the nation.

There are good economic arguments why any of those shapes could be how this recession winds up progressing.

But another good question is: How severe will this recession be?

Reuters polled more than 50 economists, and although some thought there might not be a global recession, the average estimate was the global economy will shrink by 1.2% at the bottom of the recession. That would be moderate as modern recessions go. The most pessimistic estimate was a 6% contraction, which would be worse than the 2008 recession and the worst recession since 1945.

The pessimists are well represented by Bart van Ark and Erik Lundh, head economists at The Conference Board. They predict a swoosh-shaped recession and say, “Americans should brace for a prolonged period of pain, not a swift recovery.”

They argue that the economy will contract by 6% and won’t start to recover until September at the earliest.

Even with the 2.3% growth rate we enjoyed in 2019, that would mean nearly three years for the economy to get back where it was and more years to make up for the lost time.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Vernon Smith represents one of the avowed optimists. He argues that our economy is dynamic and well placed to quickly recover.

Stating “we are neither a feeble society nor a feeble economy,” he goes on to say that businesses that will fail in this recession will mostly be small and young, and the new business that will arise in the recovery will also be small and young.

Further, Smith believes businesses that weather it will be the next generation of big firms, just like today’s big firms survived and grew in the wake of the previous recession. But this time technology is even more well developed for flexibility and reducing transaction costs, making recovery easier and faster.

“As this crisis unfolds, don’t think of decline in labor and product markets; rather think of the churn, growth and survival that is happening,” Smith says.

I’m an economist, and I am not sure who is right. Both sides have good arguments. This contraction is unusually hard-hitting on some industries and seems to be digging a bigger rather than a deeper hole in economic growth.

But at the same time, technology is enabling an amazing amount of job creation, which will be the stronger trend depends at least in part on the policy choices made in coming months.

Ending lockdowns is crucial, but it must be done in a way that deals effectively with real risks of COVID-19 contagion and also helps people to feel they understand the risks of both staying at home and of going to work and shop and allows them to manage those risks.

On the government side, that means ending one-size-fits-all shutdown policies and the arbitrary picking of “essential” versus “nonessential” and shifting to a risk-based approach that provides information and guidelines, so businesses, workers and consumers can make sensible decisions and practice appropriate risk-management behaviors.

At the same time, businesses will need to be hyper-responsible about operating in ways that reduce risks of spreading the virus. For some that will be easy and for some much harder.

Workers, customers and individuals interacting in public spaces will need to be responsible and, while managing their own risks as they see appropriate, must not impose their possible infection risk on others.

Ultimately, widespread immunity and/or a vaccine will enable economic activities to move to whatever the new normal is going to be.

State and local leaders can also bend the shape of the economic recovery with smart economic policies. The worst thing they can do is try to resume former spending levels and priorities.

It is imperative to leave more money in the hands of individuals and firms to use for consumption and investment, vital to restoring economic growth.

This is the time for hard choices and harsh prioritization in government budgets. What might have seemed to leaders like good uses of resources in an economic boom have just become luxuries. Focusing on core services that protect public safety and enable economic activity needs to be job No. 1 for the budget now.

Dr. Adrian Moore is vice president of the Reason Foundation and lives in Sarasota.