- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

A recent local news story told of four men returning from a party, who, coming upon a burning car, stopped, pulled the unconscious driver from the burning car, and, risking their lives, saved hers. This was a welcome story, particularly given the constant news coverage around that time of the tragic shootings in Colorado and Wisconsin.

The part of the story that jumped out at me was the recollection by one of the men that they flew into action without hesitation. This supports the notion that people are "hard-wired" to help others; that the desire to help others is innate rather than learned through socialization. This isn't a new theory. It's part of the long-running discussion about what makes people tick.

Part of that discussion is Rebecca Solnit's 2009 book, “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster,” which examined the aftermath of several major disasters, including the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina. Solnit’s premise is that disasters provide a window to human possibility, and that from disasters, we see what we can be in everyday life. Following exhaustive research, evidence showed that the typical response among survivors was to self-organize for mutual aid.

Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, people took their stoves out onto the streets and set up street kitchens, donating food and supplies. In the face of broken water mains, they fought fires with bucket brigades, blankets and shovels. The common description of the aftermaths by the survivors was a scene of calm and a sense of community. These observations are consistent through modern disasters, as in the stories of hundreds of private boat owners who scoured infested waters to save people stranded by Katrina. Thousands of people survived because strangers reached out to help.

Many survivors of these disasters reported an experience of good cheer and gratifying purpose in these experiences. The usual order broke down, everyday concerns disappeared and barriers, that ordinarily separated people lifted. They were faced only with immediate challenges.

This created a sense of freedom and community; and the creative cooperation and generosity they experienced gave them tremendous satisfaction. Perhaps we all have memories of similar feelings — the delight in neighborhood cookouts during the 1965 Northeast power blackout, the quiet kindness that prevailed among New Yorkers following the 9/11 attacks.

Solnit concluded that these disasters brought out the best in people, not the worst. This contrasts with the media focus on the few bad actors. It also flies in the face of the common assumption that experts are the only ones qualified to provide help in a crisis. Sometimes, experts are motivated by desire to control, or fear of panic or crime, which at best, diminishes their effectiveness and, at worst, does damage. Solnit has many examples of this kind of “backfire,” such as in the story of how officials made the fires following the San Francisco earthquake worse by driving people from areas where water mains broke and only human manpower for bucket brigades could have effectively helped.

Or there’s the story of a person who was poking through rubble and was shot dead by an officer when he refused to desist, only to discover that the man had been trying to rescue someone buried. And, of course, we need only look to Hurricane Katrina to see the tragedy that can result from reliance solely on the experts for help.

Of course, there are also many examples of the good works that professionals perform. However, the point is that regular people are uniquely qualified and ready to help; and that they do, time after time.

Is the desire to help others “hard-wired” or learned? Does the answer matter? Most people agree that the answer is in the middle. Human nature is many-faceted. Extreme situations can drive people in the direction of extreme selflessness or selfishness. It is often observed that the vilest criminals can seem to be ordinary. But maybe it's enough, for the moment, when history and experience can also show that ordinary people can be the most inspirational heroes, and that there is reason for optimism about human nature.

I am writing this on the 68th anniversary of the day on which the Nazi Gestapo captured Anne Frank and her family. That brings to mind her statement, “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are good at heart.” I am grateful to Dylan Crawley, Josh Lugo, Travis Tritschler and Michael Dudash, the four men who saved the woman from the burning car, for reaffirming the truth of that belief, and for reminding us that the opportunity to be a hero is at hand every day.

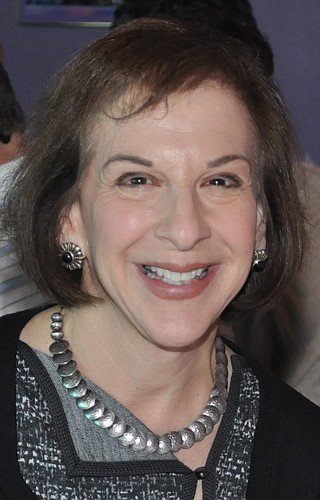

Sue Jacobson is a Sarasota lawyer and regional president of the American Jewish Committee.