- July 5, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Bob Craft ended his second tour of Vietnam in 1969, but his Vietnam War experiences never left him.

One night, when he couldn’t sleep, he wrote new lyrics to the Charlie Daniels song “Still in Saigon.” He called his version “Still in Vietnam” and emailed them to fellow veterans last May. They read in part:

We loaded up the body bags and put them on the plane.

There is nothing you can do or say to help you ease the pain.

That’s been 42 years ago and time has gone on by.

Now and then I catch myself, eyes searching through the sky.

Ten-and-a-half months later, a flag hung outside Room 4 of Tidewell Hospice in Bradenton.

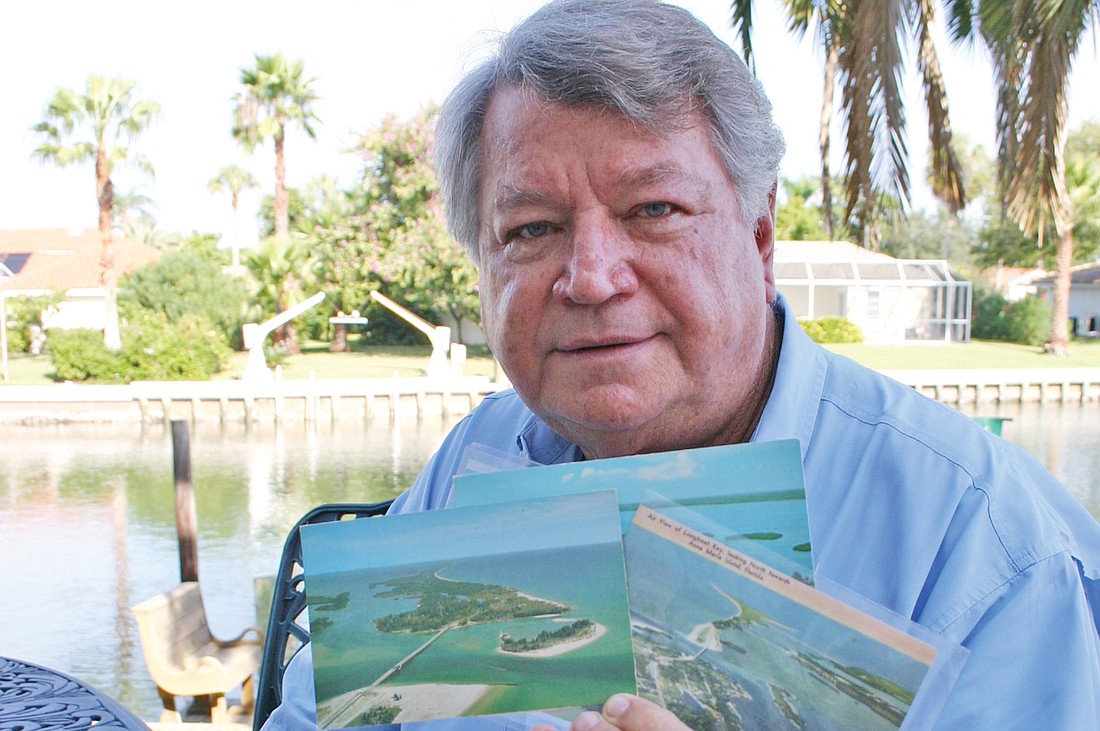

Craft lay fighting cancer, surrounded by mementos of his life: the medals he earned in his seven-and-a-half years in the U.S. Air Force; photos of him wearing his Delta captain’s uniform and smiling alongside his wife, Alycia; and a black-and-white picture of a 25-year-old Craft when he was still in Vietnam.

Craft died Wednesday, April 10. He was 70.

Two days before he died, he told the Longboat Observer, “Bob Craft is fighting his final battle.”

He was born Jan. 21, 1943, in Louisville, Ky., to a military family.

His father, Robert Craft, served 32-and-a-half years in the Air Force, earning the rank of master sergeant, one of the highest ranks an enlistee can reach.

“He said, ‘There wasn’t any question of what I was going to do in life because I was surrounded by heroes,’” Craft’s wife, Alycia, said two days before his death.

But his father didn’t want him to enlist; he’d raised his son to become an officer.

Craft graduated from the University of Florida before becoming a second lieutenant, then captain, in the Air Force. He earned a Distinguished Flying Cross, six Air Medals (one of which he earned the same day as the Distinguished Flying Cross), the Air Force Commendation Medal, Presidential Unit Citation, Outstanding Air Award and National Defense Ribbon.

He served as a pilot instructor in the Air Force from 1969 to 1973, when he became a Delta Airlines pilot.

In 1974, Craft met Alycia, then a Pan American World Airways flight attendant, at a party for Pan-Am employees who were getting ready to go on strike. They married three years later at the Ernest Hemingway House in Key West.

Still, long after he left military life behind, he remained a man with a mission.

On Sept. 11, 2001, he was the captain of Delta Flight 109, which was heading from Madrid to Atlanta.

Concerned a bomb could be onboard, he and fellow pilots made the difficult decision to land on a World War II runway on the Portuguese island of Azores to ensure the safety of passengers and crew. Ten years after the terrorist attacks, he told the Longboat Observer he had never been prouder of any crew he had flown with in his entire career.

After his mandatory retirement in 2003, Craft began devoting himself to other missions.

He attended Longboat Key Town Commission meetings, often wearing his Gator crocs, speaking about issues that riled him, such as a proposed cellular tower or potential density increases. He also offered words of support, praising police when they caught burglary suspects in his Emerald Harbor neighborhood, for example.

“He worked so hard on so many things that people would have let slip by,” said Craft’s neighbor, Anne Summers, who said he worked to ensure the neighborhood’s canals were secure and that its flag was properly displayed. “I think one of the virtues that Bob had was the level of responsibility to anything he was undertaking.”

He could often be seen with Alycia enjoying an afternoon drink at Key restaurants and bars. He often talked town politics, but bonded with many of his drinking buddies over their military backgrounds.

“I’ve seen this for years that you’ll walk into a bar and somehow the military will come up in a conversation and you have an instant buddy,” said Longboat Key author H. Terrell “Terry” Griffin, an Army veteran who used one of Craft’s stories about flying into airfield fires and smelling the burning of bodies in his novel “Murder Key.”

Outside of local politics and neighborhood issues, Craft had another mission in retirement: Once a week, he volunteered helping other veterans at the VA Hospital. He’d rally them to do the things that, faced with post-traumatic stress syndrome, they often neglected, such as paying bills and balancing checkbooks.

Griffin summed up Craft’s life like this:

“I would describe him as a warrior, an entrepreneur, a drinking buddy, a storyteller and a man who loved his wife.”

Craft is survived by his wife of 35 years, Alycia; sister, Barbara Jarvis; brother, John Craft; and two nieces and two nephews.

A memorial service will take place at a later date.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Wounded Warrior Project in Jacksonville, woundedwarriorproject.org.

Condolences can be expressed at brownandsonsfuneral.com.