- May 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Oh, the places they’ll go.

The tiny loggerhead hatchlings that emerge from the turtle nests will find their way to the water and swim away from land for three-to-six days out of the Florida current.

“Then, they basically travel the entire Atlantic gyre,” said Kristen Mazzarella, senior biologist at Mote Marine Laboratory’s Sea Turtle Conservation and Research Program, referring to the Atlantic Ocean current that stretches from the eastern United States to western Africa and Europe.

Only about one in 1,000 hatchlings will survive to sexual maturity, which is around 30 years for a loggerhead. And when they do reach that stage, the female will likely return to the same beach area where she hatched.

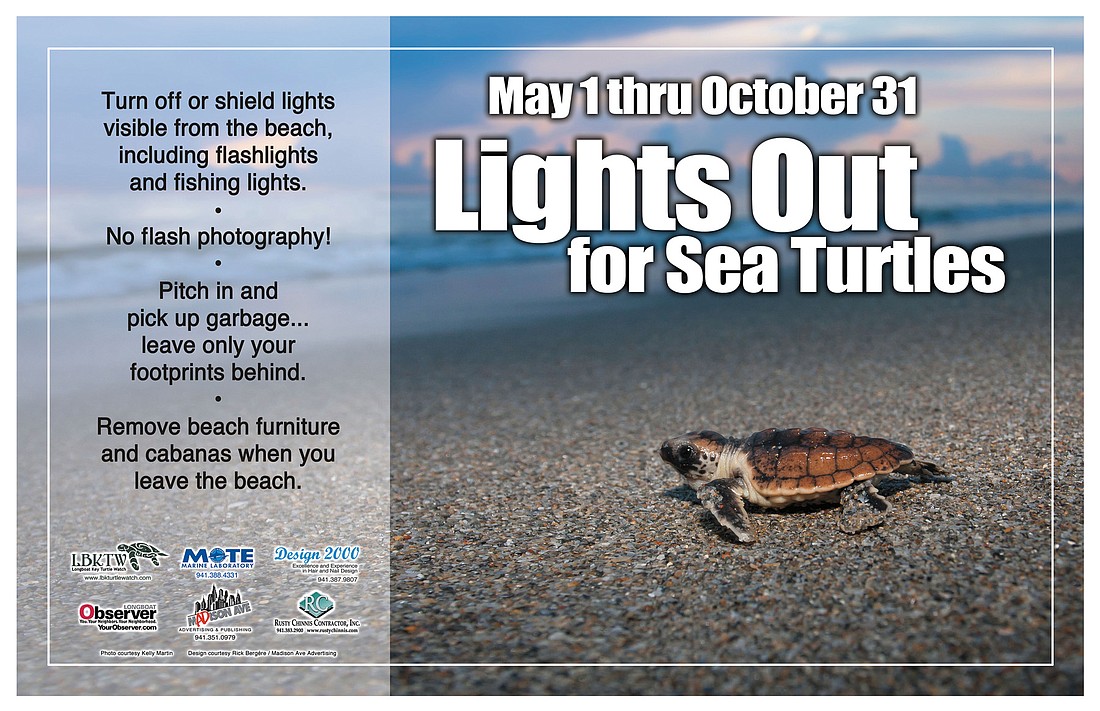

That’s why from May through October, it’s lights out for the sea turtles. Bright lights disorient nesting turtles and hatchlings, ultimately preventing the tiniest turtles from making their way into the sea to start the incredible journey that can span oceans.

Mature females typically nest every two or three years. They hang around offshore, close to their nesting area of choice, between May and August, laying four to six nests during a typical season, each of which consists of between 100 and 120 ping pong ball-sized eggs.

For the two or three years before the next nesting season, females that nest on local beaches might go as far as the Mississippi Delta or Cuba.

For the two or three years before the next nesting season, females that nest on local beaches might go as far as the Mississippi Delta or Cuba.

Nesting numbers in Florida have been on the decline since 1998, but in Mote’s patrol area (which spans from Longboat Key to Casey Key), they’ve increased in the past couple of years.

Last season, the Sarasota-Manatee area had 2,462 loggerhead nests — a record during the 31 years of Mote’s patrolling — although Tropical Storm Debby destroyed approximately 950 of those nests. Nesting numbers are also increasing on some other Florida beaches, as well.

So, what does that mean for the loggerhead population?

Researchers aren’t sure.

Loggerhead nesting and population numbers could be following decades-long cycles. Mote continues to track turtles and nesting numbers to continue gathering data that will help researchers better understand these cycles.

Loggerhead nesting in Florida has gone through periods of increase and decrease lasting about a decade each. Because nesting numbers began to reverse in Mote’s patrol area after a low point in 2007, that could mean they’re now in the middle of an upward part of this cycle.

Loggerhead nesting in Florida has gone through periods of increase and decrease lasting about a decade each. Because nesting numbers began to reverse in Mote’s patrol area after a low point in 2007, that could mean they’re now in the middle of an upward part of this cycle.

That’s why it wouldn’t surprise researchers to see more strong years for nesting numbers.

While humans can’t control natural cycles of turtle populations, they can help hatchlings survive by keeping the beach free of visible lighting, picking up garbage, avoiding flash photography, removing beach furniture and knocking down sandcastles when you leave the beach.

“Keep the beach looking like it would naturally, without humans,” Mazzarella said.

Here comes the rain again

Tropical Storm Debby pounded Sarasota County beaches in the middle of the 2012 sea-turtle nesting season.

Despite losing approximately 950 nests to the storm, according to Mote Marine Laboratory, nesting females managed to dig more than 2,400 nests during the season — nearly double the amount of nests the previous year.

William Gray, head of the Tropical Meterology Project and Colorado State University professor, and Phil Klotzbach, who has worked with Gray on seasonal hurricane forecasts since 2000, both forecast an active hurricane season in 2013.

The pair’s Atlantic Basin Seasonal Hurricane Forecast for 2013 (last updated April 10) predicts nine hurricanes for the coming season, which runs from June to November. Data the scientists used in the report shows the median number of annual hurricanes from 1981 through 2010, was 6.5.

The report predicts a 47% chance of a major hurricane (greater than Category 2) will make landfall on the Gulf Coast. The same statistic for the previous century is 30%.