- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

This Saturday marks the 72nd anniversary of what President Franklin Roosevelt declared a “day of infamy” — the day Japan unleashed its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

We lost 2,335 U.S. service men and women at Pearl Harbor — now the second-deadliest, one-day loss of Americans’ lives in war and conflict. The terror attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, surpassed Pearl Harbor in loss of life — 2,996. Many have referred to that day as our nation’s second day of infamy.

Just as we say today in memory of 9/11 that “we will never forget,” so, too, the same should continue for Dec. 7, 1941.

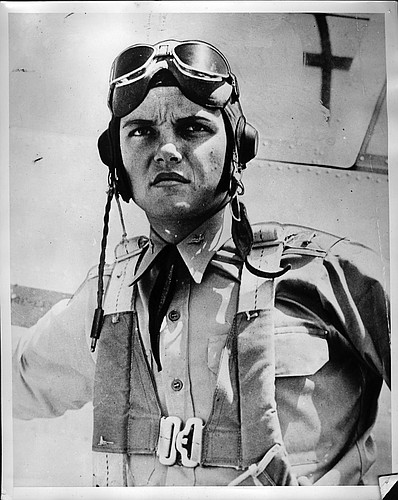

To commemorate the memory of that day, we take you there — via a firsthand account. We are printing this week excerpts on Pearl Harbor Day from the book “Letters to Lee,” by Longboat Key resident Cecelia Edmundson, daughter of the late Lt. Gen. James V. Edmundson, an Air Force hero of three wars.

“Letters to Lee” chronicles the military life and marriage of Edmundson’s parents. It’s great reading — especially if you knew the main characters. Indeed, we can’t think of anyone Longboat Key history who was a greater and more extraordinary war hero and person than Gen. “Gentle Jim” Edmundson.

Chapter 18: The Flight Line of Dec. 7, 1941

That day was one I will always remember. To a young lieutenant whose exposure to violent death and mutilating wounds had been limited, it was unreal. The day had a sense of horror and unreality that are hard to convey.

The sky was full of Japanese airplanes. Formations of high-level horizontal bombers were laying down a pattern of bombs on our parked aircraft. Dive-bombers were making individual attacks. Several put bombs into the consolidated barracks and into the flight line hangars as I was running for the line. I saw one dive-bomber go straight into the big Hawaiian Air Depot hangar without appearing to try to pull out.

Fighters and dive-bombers that had released their bombs were making strafing passes over our parked aircraft, up and down the streets and over the quarters area. It was a random operation, without opposition, and they seemed to be having a great time. In open cockpits, they wore cloth helmets, and their faces were clearly visible.

Strafing planes were carefully picking off individual men trying to make their way across the parade ground. They also seemed to delight in shooting up parking lots full of cars. Perhaps they were making sure there would be a good post-war market for Datsuns and Toyotas in the United States. Their activity seemed heaviest over Pearl Harbor, especially around Ford Island and battleship row. Muffled explosions were continuous, and huge columns of black smoke poured up.

My little squadron was hard hit. Our wing of the barracks was hit, killing many of my troops sleeping in on Sunday. The Central Mess Hall was hit in the middle of serving breakfast. My first sergeant was killed at his desk in the orderly room. The hangar that housed our aircraft, our operations, and maintenance activities took a direct hit, and I lost my line chief and my operations clerk, both of whom were at work that Sunday morning.

Much had to be done: fires put out, small arms distributed, wounded taken to the hospital, and aircraft dispersed. At various times, I was involved in doing all these things. I couldn’t begin to tell you when or in what order certain things were done.

I remember one small man, a Japanese civilian. I don’t know what his job was, but he had gone to the yard in front of the hospital where the wounded were beginning to be collected — some horribly mutilated — and this little man had somewhere found a basin of water and a piece of rag and was going from person to person wiping off their faces. It wasn’t much, but it was all he could do. For some reason, the memory of him has stayed with me.

I recall taxiing a B-18 across the runway for dispersal. It had one engine knocked out, but the aircraft next to it was on fire, and it needed to be moved. I’d rev up the one engine to the limit, and as the plane would start to circle forward, I’d slam on one brake to make the plane swing back around the other way. We duck-walked across the ramp and the runway that way, with the crew chief pounding me on the shoulder, saying, “Lieutenant, you can’t taxi these things on one engine.”

There was a squadron of B-17s arriving from the mainland that morning, on the first leg of their journey to the Philippines. They were arriving without any warning in the midst of the attack, and you can imagine the confusion. Most were low on fuel. They had, of course, made the flight without ammunition in their guns to save weight. Some landed at Hickam, with Zeroes trying to shoot them down in the traffic pattern.

Some landed at other airfields, and some went to the outer islands. I remember that one landed on the Waianai Golf Course.

One B-17 landed at Hickam with the tires shot up and a fire in the radio compartment. It slid to a stop in the middle of the runway. I was with a group trying to clear the runway, and we ran up to the airplane. The pilot turned out to be a guy I knew named Swenson. He stuck his head out the window and yelled, “Hi, Eddie! Hey, what the hell goes on here?” Under the current conditions, it seemed a pretty reasonable question.

We got him out. He had a couple of wounded on board and a flight surgeon with him who had been killed. I wanted to extinguish the fire in the radio compartment of his plane so we could get it off the runway to clear space for other airplanes to land. We got one of these big pushcart CO2 fire extinguishers from one of the hangers and rolled it out there. I climbed up and through the pilot’s window over the wing and was going back through the bomb bay to the radio compartment. The minute I turned on that rascal, I had CO2 sprayed all over my hand because the rubber in its nozzle had rotted. It froze my hand, which I didn’t realize at the time.

We got the fire out, and I climbed back down. We got wire cutters and cut the control cables because the B-17 had broken in half, in the center. We got a tug and towed the two halves out of the way so others could land.

About then, a Japanese airplane went across strafing and dropping fragmentation bombs. I felt a big bang and was knocked out. When I came to, of two guys who were with me, one was very badly wounded, and the other was dead. I felt my head because I couldn’t see out of one eye. There was blood running down, and I felt with my frozen hand. It felt like I had a hole in my head big enough to put my fist into. “Well,” I thought, “that’s all she wrote. That’s the end of the road. What can I do? I’ll just sit here and wait to die.”

I hadn’t seen anyone just slightly wounded that day at all. I sat there and waited to die, but nothing seemed to happen. Then, I reached up with the other hand and found out that all I had was a little nick in my head. Feeling very foolish, I got up and went back to work.

LETTER TO MOM AND DAD, DEC. 24, 1941

This is the day before Christmas. It hardly seems possible. Christmas this year is sure a farce. Writing to you now is almost an impossible job because so much has happened the last couple of weeks, and there is actually so little I can tell you about it. Needless to say, we had a ringside seat. Lee will undoubtedly be home before too long, and she will be able to tell you much more about what went on than I will be able to in a letter. Luck was certainly on my side. I was in the middle of everything and got away almost without a scratch.

My little squadron was hit extra heavy, and my adjutant, Lt. Green, was killed, among others. It was a horrible thing to go through. There is nothing honorable about being machine-gunned while in bed as so many were. We were so utterly helpless on the ground, and the attack itself was so wanton and ruthless. It wasn’t a fight-it was butchery.

Now that we are squared away, things will be different. Cold-bloodedly speaking, it was a cheap lesson because the American people, being what they are, had to have something like this happen before we could get any public sentiment aroused. It’s just too bad we, over here, had to be the goats, but now that we are in it, I’m glad I was here. The war is my own personal fight now. You can read about things like that from now until doomsday, and it will never mean as much as to actually have people you know and like blown in half in front of your eyes without chance to defend themselves.

Believe me, it’s only a matter of time until every little Jap in the world is either dead or flat on his face in the dirt, and I’m so very happy that my training has suited me for a major role in bringing this to pass. It’s up to those of us who know how to take over from here on, and believe me, it will be done. As soon as Lee is safely home, I’ll be able to relax and enjoy it.

As a country, we can’t help but win. As for me personally, that’s in somebody else’s hand. I’ve a job to do that I know how to do, and I’m looking forward to it. However I come out of it myself, you can rest assured I’ll have never done anything to make you ashamed of me. The American way of living and doing things is a religion with me, and one I’ve sworn to protect as an officer in the United States Army. I hope this doesn’t sound like flag-waving to you because it’s not.

Don’t worry about me. Now that we are on our feet, nobody is a match for us, and they’ll never catch us flat on our backs asleep again. My letters will be few and far between from now on, and they will be none too full of news. Will have lots to talk about when it’s all over, which shouldn’t be too long.

Remember my love is with you, and I’m proud of you both. It won’t be long.