- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

A 12-year-old James Tapley browses the stacks of the public library in Lakeland — his refuge from a poor family life. It’s the place where he finds solace feeding his rapacious reading appetite.

A book catches his eye. He pulls it down. It’s a book about French decorative arts between the first and second World Wars, and it falls open to a double-page spread on book binding — the most beautiful thing he had ever seen.

“That’s when I decided I wanted to become a bookbinder,” he says.

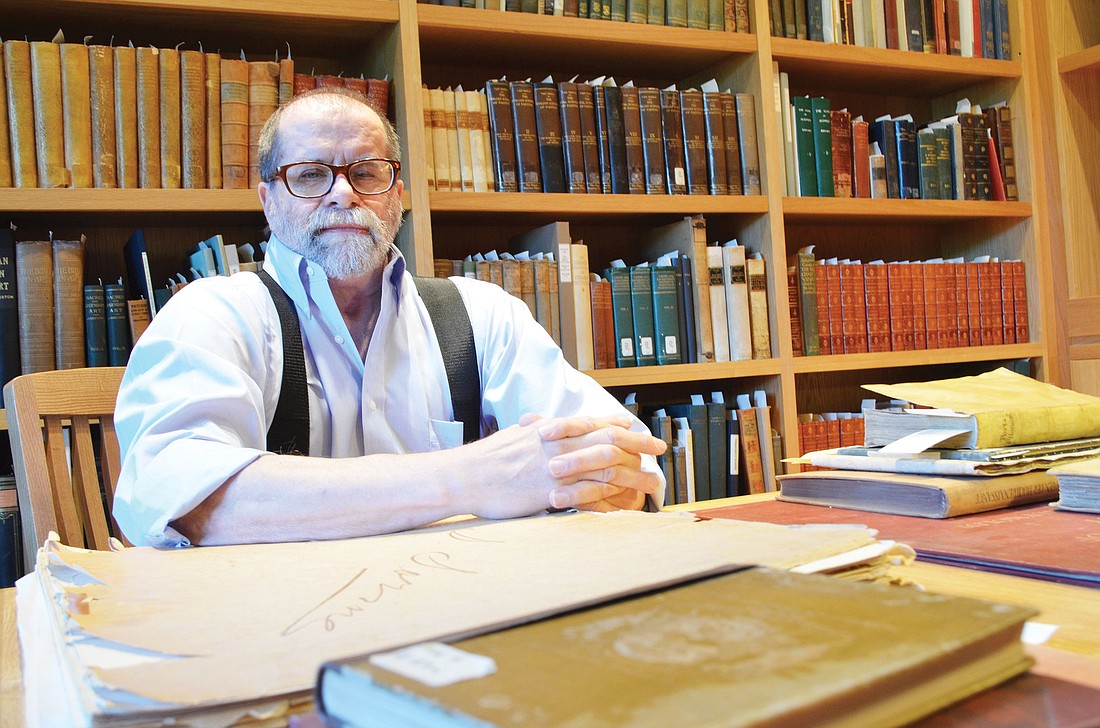

Tapley, The Ringling Museum’s 63-year-old contracted bookbinder, operates from an old 1950s tire store beginning at 4 a.m. Not-so-white noise of foreign films drones in the background as he repairs and restores old books.

The Ringling’s rare-book collection dates back to 1475 (books that were printed on the first generation of printing presses). Aside from that collection, he’s repaired everything from a collection of Egyptian papyrus to old family prayer books. Sometimes, he creates bindings for publishers’ limited-edition prints — collectors’ items bound by hand.

Many of the rare books Tapley restores for The Ringling once sat on the shelves at John and Mable Ringling’s home. These art and architectural books the couple collected informed their art purchases.

“You don’t get the idea he bought things just to impress someone else,” Tapley says. “You get the idea the only person he was interested in impressing was himself.”

Tapley knows because he reads everything he restores. He’s the kind of guy you’d hate to oppose in Trivial Pursuit. He can tell many things about baroque master Peter Paul Rubens or many of the other artists who make up the permanent collection.

When he works on rare books, he might strip the book down to individual sheets of paper and rebuild it to a condition that will preserve it into the future — what he calls “minimally undoing all previous damage.”

If he’s lucky, the book he’s working on hasn’t been repaired before. Advances in materials and science make books that were repaired decades ago nightmarish.

“We look back at horror on what we actually did in those days,” he says.

He also hates library tape stuck down broken splits — tape produces degradation and byproducts that further deteriorate.

“Tape is a four-letter word,” he says.

He’d never use tape on his own collection vastly devoted to books about bookbinding.

He could tell you the whole history of bookbinders: how books have become increasingly shoddy compared with their 15th-century counterparts, when 250 books were printed per press run on fine Italian paper with high-quality ink, press work and book bindings. As more people became educated, there were higher demands for more copies, and printers had to cut corners.

Tapley thinks books as an object are not going to disappear.

“There will always — always, always, always — be a need for a hand bookbinder,” he says. “There will always be a need for someone who can deal with books as unique objects.”

James Tapley’s binding opinion on:

Dog-eared pages: “Don’t do it! But, it’s not the worst fate. The worst fate a book suffers is to never be opened, never be used or never be loved.”

Cracked spines: “Don’t do it! But, again, it’s not the worst fate.”

Electronic readers: “I have a collection of digital books because there are a lot of books I want to have that I can’t afford or copies aren’t for sale. For example, bookbinding literature, of which only a handful of copies exist in European libraries. And thank goodness Google digitized them for me.”

Paperbound books: “On one hand, you get what you pay for. On the other, not everything needs to be built to last forever. Do you really want 500,000 copies of ‘Love Story’ to survive into the next century? We don’t really need that. Paper books are great. Plus, you can take them into the bathtub.”

Library tape: “Don’t use it.”