- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Kevin Dean once said, “History books can only tell you so much — when you meet the people, that tells you a lot more.”

Kevin Dean once said, “History books can only tell you so much — when you meet the people, that tells you a lot more.”

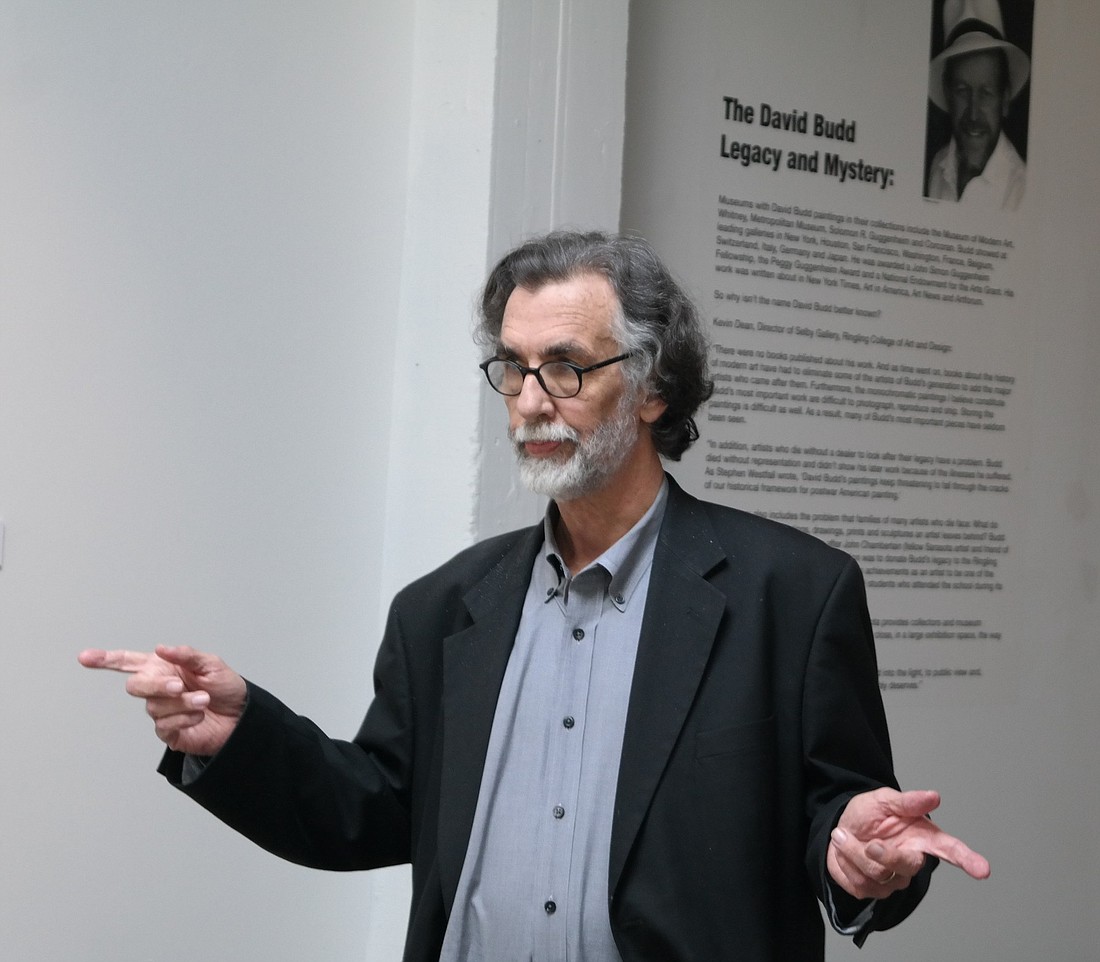

If you were fortunate enough to meet Dean, then you’d never forget him as the artist-meets-rock-’n’-roll-fan product of the ’60s: tall with long, disheveled hair, a pepper-gray beard and thick black-rimmed glasses.

The 64-year-old was the perfect picture of an absent-minded Ringling College of Art and Design professor — remembered as never having hubcaps on his Toyota Matrix and always wearing black Aqua Socks, the slip-on water shoes.

Dean was quiet and unassuming. Visitors of Selby Gallery, where he was the director since 1994, would meet him without realizing his impact on Sarasota arts. But, for 35 years until his death May 13 following a brief illness, Dean gave a voice to the visual arts.

Just like in the movies

Dean was always a teacher. While he was obtaining his master’s degrees in studio art and art history from Western Illinois University, he taught art in public schools and at a community college. But his first job as a curator was in Galesberg, Ill., where Dean ran the Galesburg Civic Art Center beginning in 1976.

Attempting to gain some publicity for an exhibition, he ventured into the building of the town’s daily newspaper, The Register-Mail. He spoke with a blue-eyed blonde, Kay Kipling, who hadn’t been on the job for even a week as a features writer.

“He was intelligent and funny,” she says. “I thought he was a little offbeat — I like offbeat.”

The duo clicked. They went to see Clint Eastwood’s “The Outlaw Josey Wales.” Afterward, they talked for hours. It was the first of many movies they’d watch together throughout their relationship. They were married in 1978.

A visionary voice

In 1979, Dean and his new wife moved to Sarasota. A year later, Dean approached Ralph Hunter, the publisher of the Longboat Observer at the time, and said he wanted to write an arts column.

“My wife told him to, ‘Go out and get yourself a haircut and a shave, then come back,’” Hunter says.

Plus, Hunter said he’d oblige if Dean sold a page of ads.

Dean had never worked in sales, but shortly after the meeting he returned with a page sold. Eventually Hunter agreed to let him stop selling ads and hired him full time (even though Dean never did get that shave or haircut).

Aside from Ralph and Claire Hunter’s daughter, Janet Hunter, Dean was the first full-time employee of the Longboat Observer. Janet Hunter said he always surprised them with hidden talents: from being resident cartoonist to helping the paper win a baseball game as pitcher. The Hunters say he was a writer ahead of his time.

“He had so much knowledge and vision for the arts community in Sarasota and a frustration with people’s lack of acceptance of creative forms of art,” Janet Hunter says.

He modeled himself after his favorite art critic, Robert Hughes, who wrote for Time magazine. He thought Hughes was funny and could reach people on their level — Dean’s same approach.

“I didn’t do what critics do that sounds like you’re talking to other critics,” Dean once said in an interview with Diversions.

He wrote about the artists and the community when the visual arts scene was booming with nationally recognized artists such as Syd Solomon, David Budd, Ben Stahl and Robert Chambers. Dean was at the nucleus of it all as the authoritative voice preserving Sarasota’s art history.

Sharing his passion

The same year his first child, Ian, was born, Dean began teaching studio and art history at Ringling College of Art and Design (RCAD) in 1985. He still wrote for various publications, including the Longboat Observer, and was creating art and exhibiting it on the side.

“He was one of those people behind the scenes,” Mark Ormond, RCAD colleague and friend since 1983, says. “He didn’t seek out the limelight, but he had a connection with artists and the community.”

Although, Dean was in the spotlight when his rock band of RCAD colleagues, “The Art Sharks,” played. Dean was the drummer, and occasionally his wife would step in as the singer.

Dr. Larry Thompson, president of RCAD, calls him “the ultimate educator.” Thompson’s son, Hunter, told his father Dean was the best teacher he ever had.

“He found what he was meant to do and he was meant to be,” Larry Thompson says. “He was so passionate about it; he loved our students.”

One of those students was Tim Jaeger. Jaeger says Dean used to take out one student a week to lunch. He estimated once that multiplying the price of pizza by the number of weeks he worked at RCAD, Dean spent more than $50,000 on his students throughout his career. Jaeger continued working with him at Selby Gallery as the gallery assistant.

“He was one of the very few real and rare people that had a passion for art,” Jaeger says. “He was totally genuine.”

Introducing Whitcomb

Early in his career, Dean created paintings and collages. His work evolved into printmaking and constructions with yardsticks or wood. For the past two decades, he created site-specific installations with found materials; each piece had a symbolic meaning. Dean labeled it “Neo-dadaist postmodernist conceptual” art.

His last installation, “Whitcomb Series: Dreaming of my Cabin in the City of Dis,” was featured in “All in the Family” at the IceHouse (curated by Jaeger). It was a small shed-like cabin surrounded by Mason jars full of various items, a parallel to Dante’s “Inferno.”

Often during the past 20 years, Dean would create art under the pseudonym Brandon Whitcomb. Dean would even give lectures at colleges about Whitcomb and introduce Whitcomb and his art as if he was a separate entity. Dean was writing the fictionalized biography of Whitcomb, which was really a reflection of Dean himself.

Talking shop at Selby Gallery

Dean continued teaching and creating art when he became director of Selby Gallery in 1994 (two years after his daughter, Molly, was born). Laura Avery, assistant director of the gallery, describes his office as one of his installations, “the inside of his mind.” He displayed his collected iconography of the Catholic Church, tchotchkes his students gave him, paintings and the funny and tacky gifts he cherished.

He curated more than 250 exhibitions during his time at the gallery. His mission was to enlighten RCAD students and the public about the contemporary art taking place in big-city hubs from Los Angles to New York City.

When people would walk in the gallery, he’d love to talk about the work in display with them.

“He never got tired of (art and art history),” Kipling says of her husband. “He just wanted to share that.”

His legacy lives on, not only in the words he left behind, but in his children. Molly Kipling Dean is an illustrator with one year left at RCAD; Ian Kipling Dean is a photographer and RCAD alumni — their father featured his work alongside theirs in January in the IceHouse’s “All in the Family.”

“So many children of artists become artists; it suggests that artists are often born and not made,” Dean said.

Dean is survived by his wife Kay Kipling; son Ian Kipling Dean; daughter Molly Kipling Dean; two brothers, Ken Dean and Keith (Sally) Dean; sister Karen Bunn; and many friends. A memorial service will be held 2 p.m. Sunday, June 8 at Selby Gallery, 2700 N. Tamiami Trail.