- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

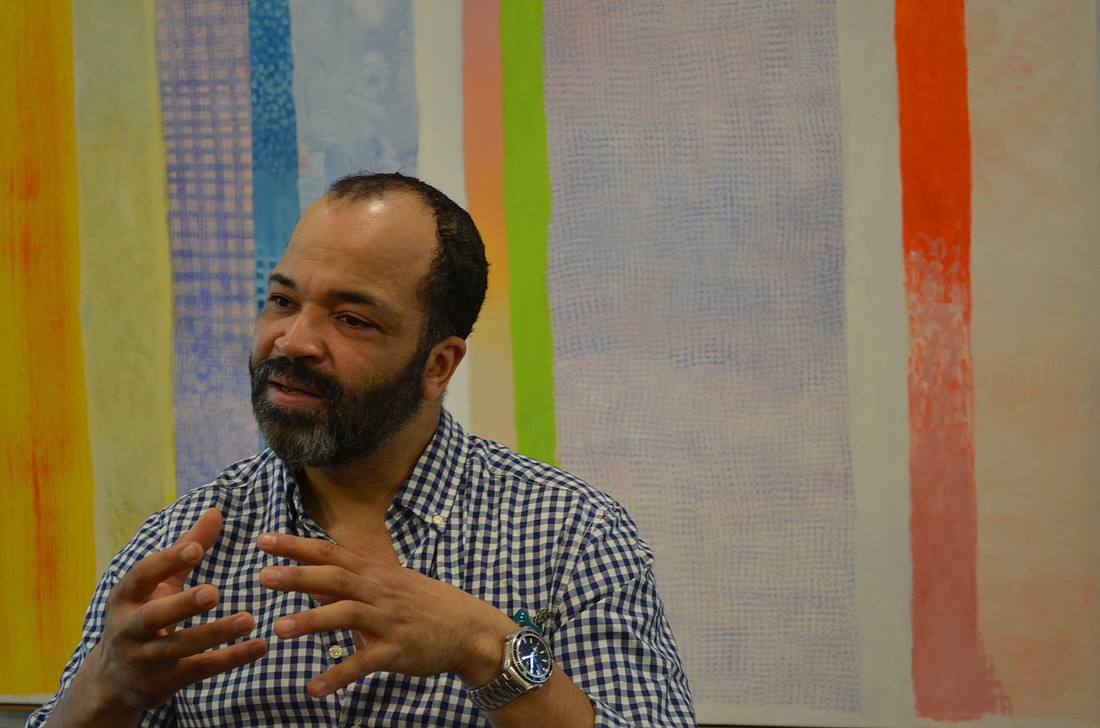

Jeffrey Wright is an electrifying enigma in the acting world. A proven master of both stage and screen, Wright has quietly amassed one of the most diverse and accomplished resumes among actors of his generation. Born in 1965 and raised in southeastern section of Washington, D.C., Wright says he grew up in a political family. So when he studied politcal science at Amherst College, he thought the field of law was calling. However, after following his intuition and trying acting and performing his junior year of college, he couldn't stop. Theater and film lovers are all the more fortunate for that junior-year risk. From his Tony Award, Emmy and Golden Globe award-winning turn as Belize and Mr. Lies in Tony Kushner's "Angels in America," to impressive turns in such diverse films and televison shows as "Basquiat," "Shaft," "Boycott," "Ali," "Broken Flowers," "Syriana," "Casino Royale," "W.," "Cadillac Records," "Source Code," "Boardwalk Empire," and "The Hunger Games" franchise, Wright has made a huge impact in the world of acting.

In addition, Wright took his high profile status as a succesfull actor and co-founded the Taia Peace Foundation which advocates and raises money for African human rights, health infrastraucture and humane mineral extraction. Wright stopped by Sarasota to give a master class to film students at the Ringling College of Art and Design on April 7. He sat down and talked about his beginnings in acting, the actor/director relationship and the current state of Africa.

On selecting his next acting projects:

That varies like the pieces. My reasons for wanting to be involved in a film, series or play have changed over time. I think at the core what I’m most attracted to is language and story, narrative – and character is born out of that – but it’s really about the writing and if it strikes me. Lately in the past few years I was also drawn to the idea of not having to go away from my children for too long. There are all these various things that come into play. Related to work it’s primarily about story and if the narrative and the character makes an impression on me when I initially read it. And then as well the cast of characters that are drawn together to help tell that story. I’ve learned over time that it’s best not to work in places where there are too many assholes you know. The more you can avoid doing that the more you enjoy your time spent working together. For example, we’ve spent a lot of time together working on “The Hunger Games.” I’ve made three movies with that group. You want that to be an enjoyable setting, a group of people that you bond with and feel open to creating with. That’s a part of the decision making process as well.

On the influence of his colorful characters on his life:

I am Dr. Narcisse, through and through. That’s an interesting question. I’m not an actor who works and stays in character on set. Everyone has their process but for me I think that’s ridiculous. I do think there are elements, I’m not sure they’re elements that stay with you or elements of yourself that you bring to the characters that continue with you. It’s kind of dual forces working together because you’re creating these things out of your own clay. I’m not sure whether they stay with me or if they are me. What I can say is that if you look at the entirety of what I’ve done, somewhere within all those various characters is a composite of me. I can’t really create those things that I’m not. I hope I can be open enough and imaginative enough to be flexible and empathetic with a wide range of perspectives. Somehow they cobble together to refashion who I am and I hope Dr. Narcisse is a very tiny percentage of that person.

On switching from a political science major to acting:

I started acting my junior year of college. I was focused on political science. I grew up in Washington, D.C. in a very politically oriented family, a lot of lawyers running around the house. I assumed I’d add myself to that list. But knowing in the back of my head even this idea of performing and acting I feared it for a number of reasons. I had all of the kind of actor nightmares conspire on me at once from forever doing it and trying it until I got to my junior year. A friend of mine took a class and put on a production afterwards. He asked me to come watch it and I went and I thought, “Wow, I can do that at least.” He was terrible. So I took this class. You asked me if I imagined that I would be working as an actor and doing this at any point then, I realized the first day of this class that that’s what I wanted to be doing. I’m not sure that’s the entirety of what I want to because I still use my political science background in other ways. It was very clear early on that this was a place I was designed for. What I’ve tried to do as well is bring those elements from my political science background to a lot of work that I do too. I try to find things that resonate with me and that seize me interest. There’s no denying that I came from that background, so things like “Syriana,” “Angels in America,” and even “Boardwalk Empire” have these political and social commentary about them that I find very satisfying as an actor. It’s the music I like to play. So it’s not an entire departure from that, so I imagined it all from the start. I had this grand vision of how I was going to marry my political science background and the theater together and working on natural resource projects.

On his impression of Ringling College of Art and Design:

This is a very interesting space that young students are being allowed to explore within. I’ve just had a chance to get a sense of it. There are two kind of seemingly competing things that are happening it seems to me. While there is a preparation being laid for students to be participants in an industry, not unlike automobile making during the early Industrial Age in Detroit with Henry Ford driving that sector’s development. Likewise this is an industry. Graphic design, animation and computer modeling and all these things. But at the same time there’s such a fascinating level of creativity that can be explored through these industries. Students are being given an opportunity to express that imaginative process and those visual dreams that they generate. At the same time, they do that in a way that allows you to be a productive member of society is seemingly contradictory.

It’s very exciting for that reason to get to know what’s happening here. And also to think about the ways in which society and industry is evolving. We still need farmers and mechanics, but at the same time you have the opportunity to find this type of work for yourself is a really productive thing. I’m curious though about the student who comes here who can not only figure out a way to craft and master the language of the industry but also create new language that drives the industry and expands the creative imaginings of the place. Not everyone is going to be Martin Scorsese, but someone is. It seems to me there’s space for each of those. For that person who’s simply creative and that person who is an outlier in their creative in the walls here. That’s pretty cool and very exciting. It’s a surprising discovery for me coming here. I’m very excited about what I see.

On his Taia Peace Foundation and Africa's future:

We’ve been working at my group Taia, there’s a foundation and a company, it’s a hybrid of commercial and philanthropic investment. I was actually just in Sierra Leone a month ago. Don’t worry I passed my Ebola free test. The New York Department of Health was calling me twice a day to monitor my temperature and all that stuff. It got a little creepy at one point asking me where are you traveling and where are you going. I don’t think you need to know all of that. We’re not the Soviet Union after all. But I understood that they needed to do what they felt they needed to do. But I’m digressing. My focus there has been on this hybrid of commercial and philanthropic investment around natural resource development. What’s spoken of relative to natural resource development there in places like Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia is there’s a resource curse that these places are cursed by their mineral wealth. I think rather what these communities suffer from is more akin to a “Cassandra Curse” like in the Greek mythology whereby Cassandra was cursed by Apollo with telling the truth but no one believing her. What these countries and people say is that we have these strengths and though vulnerable we have incredibly dynamic people, culture and wisdom here. There’s an absence of capital here there’s not an absence of value.

If you look at the Ebola outbreak for example, we’re potentially seeing a replication of this Cassandra Curse whereby people are saying what they need but in the West we’re not responding to it. It’s not that people need things. It’s not that there’s a dependency that we need to create. There are partnerships that need to be created that we’re missing. For example, when Ebola came it was nuts here. People were freaking out in America. People thought we were on this straight path toward oblivion that was fueled by this virus. What people failed to realize here in America and other parts of the West that it wasn’t such a clinical problem, it was more an economic problem. It was a ferocious and aggressive virus, but it was the same virus that affected people in Dallas and southeastern Guinea but it was a different result. That’s because there’s very minimal health care infrastructure in those communities in particular in the rural parts. That’s where we operate, about 40 miles from the first case right on the Sierra Leone and Guinea border. There’s nothing like a modern hospital in that area. There are no healthcare delivery systems in that area. It’s just sparse and people are on their own, and so it’s spread out over there because there was nothing to stop it. Whereas here we have hospitals, ambulances, human resources, capital resources and all those things we need to bring to bare to shut down this outbreak we have so there was no need for us to worry.

So now what the governments and folks who have insight into these things are saying that these areas need hospitals, they need infrastructure, they need healthcare delivery systems particularly in rural areas, they need human capacities and all that stuff. But what we in the West are saying is well we need to respond better next time. The international community needs to respond earlier. Doctors Without Borders needs support. But it shouldn’t be the responsibility of the international community. It needs to be the responsibility of those governments and those communities to care for themselves. We’re not expecting Doctors Without Borders to come to Sarasota if something breaks out. We expect that we’re going to take care of it ourselves. And likewise we shouldn’t be infantilizing when we think about these communities. I was at the E.U.’s Ebola conference in Brussels a couple of weeks ago. The heads of state there like president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, president Ernest Bai Koroma of Sierra Leone, and president Alpha Condé of Guinea. What the presidents of the region are asking for is a Marshall Plan much like in Europe at the end of World War II whereby the United States government worked in partnership with these regional governments to help them rebuild after the war, to work in alignment with their national plans. It wasn’t in imposition with United States agenda onto the agenda of these 17 European countries. If we just did that in Africa, I think we’d probably see better results in the long term so the international community doesn’t have to come back five years from now and try to revert another crisis.

We were there ten years ago with the end of these wars there. Why are we back ten years now? All of these medical NGO’s and Doctors Without Borders and all those groups were there ten years ago to end the war. Why didn’t they build a hospital? Why are they back five years now? Just build a hospital and healthcare delivery systems and you wouldn’t have to siphon all the money that’s supposed to go to these governments and these communities goes to them. They can take care of the wellbeings of their own communities.

On his master class with Ringling College filmmakers:

I’ve got a little insight into what is being asked. It’s great that these are directors and filmmakers who want to gain some understanding of what the process is for an actor. What I’ve found as an actor working with a number of directors over the last 20-odd years I’ve been working is that most directors really don’t know what actors do. Most don’t and most don’t know how to communicate will with actors. It could be in a variety of ways. One of the most unfortunate things for a director is to be afraid to get into an actors mess. To be afraid to get in and find the ways to mold the clay of an actor’s performance the way an animator molds their clay whether it be actual or digital. I think it’s going to be fun to talk about it from that perspective. Even if you’re the best filmmaker will maybe make five movies over the course of ten years. In the course of ten years, an actor could work on 30 movies or you could be in the theater as well and perform hundreds of performances in an year. How as a director, if you’ve only worked on five movies, can you talk to somebody who’s performed 5,000 times? If I can share that with a group of filmmakers, I’ll gladly do that so they don’t go through life torturing actors and ruining their performances. It’ll be my gift to future generations of actors.

On the difference between voice-acting and live performance:

I just did an episode of “The Venture Brothers” and I’m about to do a Pixar piece “Good Dinosaur.” And I’ve done another piece called “Bremen Town Musicians” that’s not out yet that’s a feature length. It’s actually very challenging. Even though you’re only using your voice, you’re implying a body. I do a lot of voiceover as well. I do documentary narration. I do commercial voiceover. There’s no body implied. But when you’re doing these animated movies, it’s implied that there’s a full life that’s happening. I’m not sure about this process yet, but as I think about it is that you play the body too and let all of that happen. It’s very tricky when there’s just a microphone in front of you and you don’t have a space to play in. It’s a tricky performance balance I think at least for me. How you can break out of that and animate the body and the voice through the mouth is the trick to it. The biggest thing about any filmmaking is collaboration. When you can find that space where you trust the director or the filmmaker to craft those parts in which you want crafting, then that’s a wonderful marriage. The best part about filmmaking is collaboration. The most satisfying part is about collaboration and the most frustrating part is collaboration. It all depends on who’s at the party.