- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It had been more than 35 years since “Marguerite and Armand” was performed. Choreographed in 1963 by Sir Frederick Ashton specifically for iconic ballet dancers Dame Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, the ballet was considered nearly sacrilege for anyone else to perform after its initial run.

But for the ballet to live on, it had to be passed down to the next generation.

“I was originally with the group of people that said it should never be done without Fonteyn or Nureyev,” says Sarasota Ballet Director Iain Webb. “But after seeing it again, I thought, ‘God, wasn’t I stupid.’ I was wrong to think no one else should do it or see it. It’s a masterpiece.”

It laid dormant until 2000, when Ashton’s estate began granting revival productions. It has been brought to England, Italy and Russia. Now, the ballet is finally coming to America.

On Nov. 20 and 21, the Sarasota Ballet will be the first American company to perform Ashton’s tragic love story.

To bring that masterpiece to life in three weeks’ time, Webb invited an old friend of his and the ballet’s back to Sarasota. Grant Coyle is the principal dance notator for the Royal Ballet in London. An expert in Benesh notation (a ballet language that records choreography on a score sheet) and British choreography, Coyle has taught “Marguerite and Armand” to companies around the world, including the La Scala Ballet Company in Milan and the Mariinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“Ballets have to be done in order to survive,” says Coyle. “The ballet is living now, which is good. They need to be done to get better in a way and also enrich the dancers that do it.”

For Coyle and his company of dancers to live up to the ballet’s pedigree, every element — the steps, movements and acting by the leading lovers — must be perfect. This is history in the making.

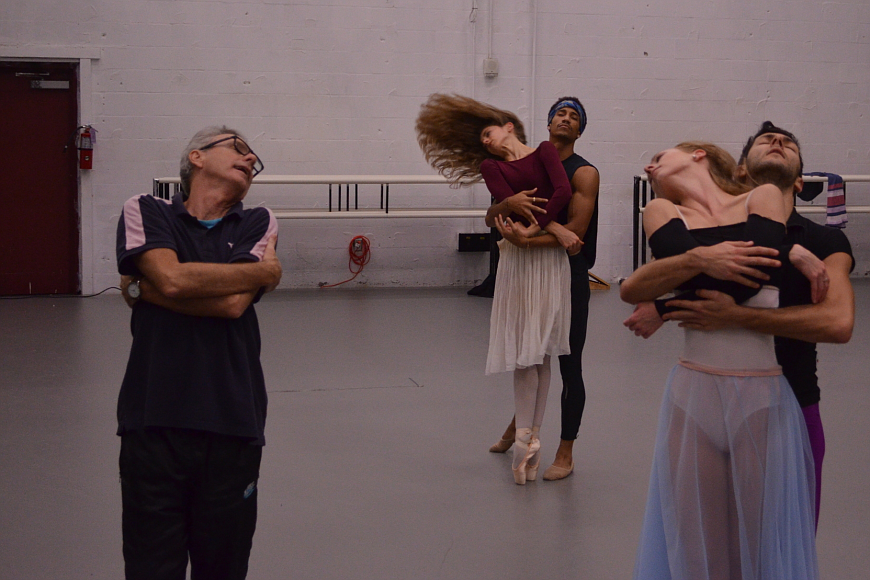

According to Coyle, passion is just as important as precision. On day three of rehearsals, he’s helping principal dancers Ricardo Graziano and Victoria Hulland focus on conveying the emotion found in the piece.

Graziano flies from the opposite corner of the studio and lifts Hulland off a bed with a fiery spirit. The two dancers spent the next hour and a half of that Friday afternoon lifting each other across the length of the studio.

Coyle watches the couple with exacting detail. Just as Graziano raises Hulland into the sky on his shoulders, Coyle stops the two dancers mid-flight. He walks them back and shows them every step and motion as they should be executed, all the while humming the ballet’s score: Franz Liszt’s “B minor Piano Sonata.”

As the first American dancers cast in the ballet, Graziano and Hulland were a little intimidated at first. But the wealth of the characters and the story helped them forget about the ballet’s pedigree and just focus on mastering the steps in the moment.

“We don’t always do story ballets, and there is a lot of acting in this piece,” says Hulland. “It adds a whole other element to the rehearsal process and helps you learn the steps more quickly in character.”

The story depicts a Parisian courtesan recalling her last great love affair as she’s succumbing to tuberculosis. And as Hulland begins to die in Graziano’s arms, the two are combining Ashton’s steps with watered eyes and mourning faces that anticpate Marguerite’s slow demise.

“The challenge is to get it right and to perfect it,” says Coyle. “Doing things over and over again helps the dancers put something of themselves into the piece. That’s when a ballet really moves an audience. It’s no longer just a series of steps. It’s an emotional journey.”