- May 8, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

After graduating from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in 1948 with no honors, Dr. Robert Morrison had this insight: He would spend the rest of his life working, so he might as well be the best he could be.

Morrison read voraciously, attended every lecture he could and took specialized classes on weekends, all while building his optometry practice. In his quest to be the best, he invented the soft contact lens and improved the vision of at least 60 million people. His patients included 17 royal families, seven consecutive Pennsylvania governors and celebrities such as Barbara Walters, Sharon Stone, Sean Connery and Chuck Norris.

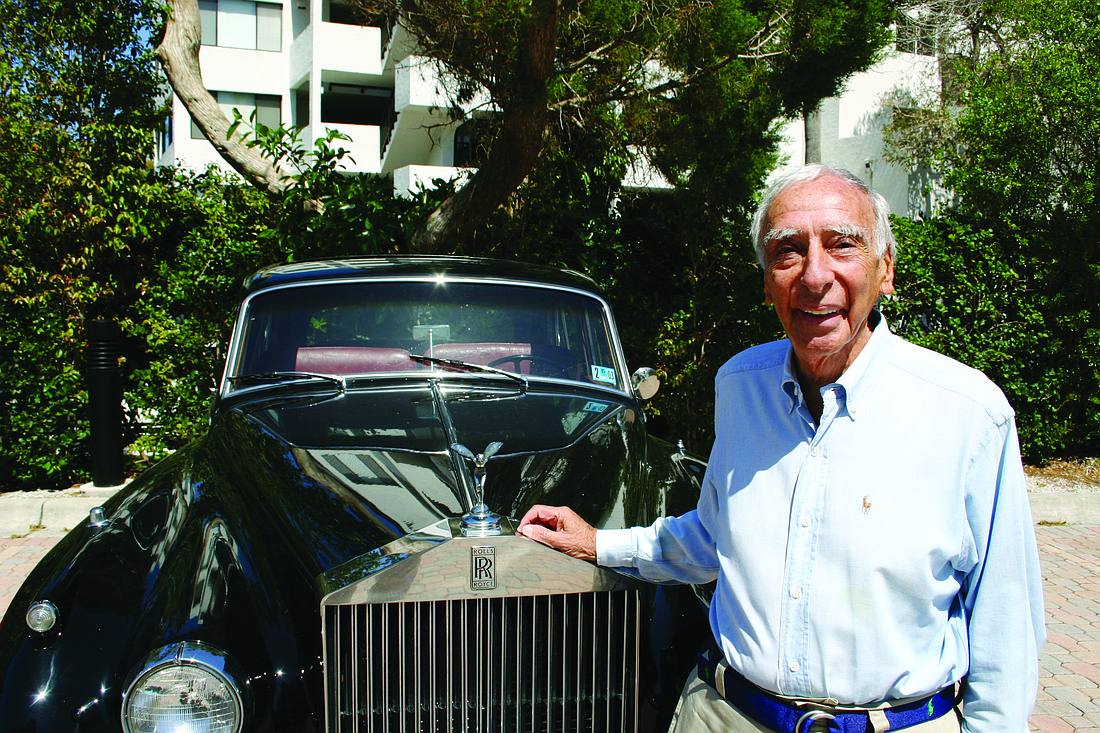

Morrison, of Longboat Key, died Jan. 7. He was 90.

He found it “fun and flattering” to treat celebrities and royalty, but he noted that the eye care was the same no matter who the patient was in an interview included in his 2006 biography, “Man of Vision: The Story of Dr. Robert Morrison,” compiled by Rosanne Knorr and Kevin Kremer.

“It was almost unrealistic because in all those years, there never was a bad day at the office with Dad,” said Morrison’s daughter, Patty Schimberg. “Every single patient was interesting to him.”

His work wasn’t limited to the rich and famous. Prince Bernard of the Netherlands knighted Morrison at the United Nations for his work in developing countries.

In a 2005 interview with the Longboat Observer, he attributed his success to “having more energy than brains” and “good timing and a little luck” before admitting: “Hey, what can I say? When you’re good, you’re good.”

Born Dec. 1, 1924, in Harrisburg, Pa., he focused more on socializing and sports when he was in school.

Even after he focused on his career, he never lost his passion for sports or socializing. He remained an avid tennis player after he and his wife, Ruth, retired to Longboat Key part time, and despite a cancer diagnosis in 2000 that required him to consume a 100% liquid diet, he frequently joined friends for dinner because he loved the company.

Morrison enrolled at Pennsylvania State University for a year, then enlisted in the Army in 1943 and served in camps and hospitals throughout the U.S.

When he returned to school, he contemplated premed studies, but worried about whether he would be accepted to medical school. After his younger brother, Vic, took a summer job with an optometrist that sounded fascinating to Morrison, he opted to enroll in optometry school.

After graduating, Morrison opened a practice that grew rapidly. Soon, nearly a dozen surgeons in Harrisburg were referring their patients to Morrison.

In the 1950s, Morrison noticed that myopia in children and teenagers nearly always progressed when the patient was fitted with eyeglasses, but the progress was slower or nearly nonexistent for youngsters who wore rigid contact lenses. Time Magazine ran a story in 1957 explaining Morrison’s theories, and the offices of eye doctors throughout the country filled up with children and teenagers whose parents sought to preserve their vision with contact lenses.

But rigid contact lenses were uncomfortable for patients. In 1961, Morrison learned that a professor in Prague had created an artificial jaw from a plastic that was hydrophilic, or water loving, that Morrison suspected could be a good fit for the eye’s liquid environment.

Morrison was on a flight to Prague the same day he learned about the hydrophillic plastic. He spent 10 years developing the new lens before selling the patent to Bausch and Lomb.

Morrison’s career as optometrist to the stars began when he got a call that he first thought was a prank from a man who claimed to be the personal physician of King Baudouin of Belgium. The king had sought soft contact lenses from five doctors, but none were comfortable. After Morrison found the right fit, he gained a following of royals and celebrities, many of whom became his personal friends.

“He had the kind of life a lot of people dream about,” said Bernard Orbach, who befriended Morrison 65 years ago in Harrisburg and now lives on Longboat Key. “There were some times you had to ask yourself if it was really true, but he actually did these things.”

He played tennis with Prince Albert of Monaco and Bill Cosby.

The Shah of Iran paid Morrison a visit in Harrisburg and felt the water of the optometrist’s swimming pool and said it was cold. Morrison quipped, “I would heat it if I could afford it, but the price of oil is too high.”

Lynda Carter, aka Wonder Woman, gave Morrison an autographed photograph that stated: “You are a beautiful man!! Now these eyes can see.”

In retirement, Morrison traveled the globe for the World Health Organization and taught at Penn State. There, the once mediocre student shared this insight: Do your best, no matter who the patient is.

“I tell my students to do the same, because you’ll only feel OK if you do your best,” he told the Longboat Observer in 2005. “After all these years, I can now look back and say that I feel good.”

Morrison was preceded in death by his wife of 58 years, Ruth. He is survived by his son, Jim Morrison; daughter, Patty Schimberg; and four grandchildren.

A service took place Jan. 11, at Temple Beth Israel.