- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Marie Selby’s favorite flower was a rose, not an orchid.

However, 40 years later, it is orchids and other epiphyte plants that have put Marie Selby Botanical Gardens on the map as a world-class botanical gardens.

“We lucked out, it could have been a prickly succulent,” said Cathy Layton, chairwoman of Selby Gardens’s board. “One of the wonders of Selby is that the early brains involved decided of all the plants that they could focus on that they would do epiphytes, and that our culture would come to love and appreciate epiphytes.”

Epiphytes, such as orchids, bromeliads, aroids, cacti, mosses and ferns, are easy to spot due to the fact that they grow upon or are attached to another plant or object for physical support.

Orchid-lovers can thank Dr. Carl Luer for the decision to take the gardens in the direction toward epiphytes. But first he had to secure the grounds.

Bill and Marie Selby

Bill and Marie Selby started visiting Sarasota in 1909 — they loved spending time outdoors. Bill Selby, a sportsman who had made his fortune through his family’s oil and gas company, spent his time hunting and fishing. In the mid-1920s they decided to build their retirement home on five acres along the Sarasota bayfront. Marie Selby planned the landscaping around the home and planted flowers along the roadway and peninsula of the property.

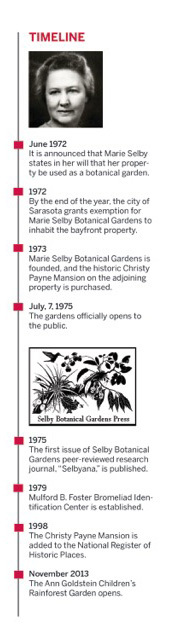

Without any heirs to their estate, the Selbys created the William G. and Marie Selby Foundation with Palmer Bank as its trustee. Bill Selby died in 1956; a year before his death he set up a charitable trust with $3 million. In June 1972, a year after the death of Marie Selby, it was announced that she willed her home, grounds and adjacent vacant lot to the north of the property to be used as a botanical garden. She left $2 million to provide an endowment for the gardens’ operation and maintenance; the remaining $16.5 million from the estate was left to the foundation.

Dr. Carl Luer, a surgeon in the area, served as a director for the board at Palmer Bank. In a paper Luer submitted to “Lankesteriana,” Lankester Botanical Garden’s scientific journal, he details how he was able to convince then Palmer Bank Board Chairman Bill Coleman about the feasibility of creating a botanical garden. When Luer presented the idea to the board, initially there was no enthusiasm. But, in private, Coleman was receptive to Luer’s proposal.

The board voted in favor of Luer creating Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. But the gardens faced opposition from the City Commission and the city’s building, planning and zoning boards. Among the concerns about the property and gardens were traffic, taxing, parking and the impact on the neighbors. At the end of 1972, the city granted permission to build the gardens.

Luer sought consultation from experts at the University of Florida and New York Botanical Garden.

Once it was determined that epiphytes would thrive at the location, he sought the help of one the best-known orchid scientists at the time, Cal Dodson, to help guide Selby. Luer went as far as flying down to Ecuador, where Dodson was living at the time, to persuade him to join the team at Selby.

“There was really a unique camaraderie between those early people realizing what potentially important work they were doing,” says Director of Botany Bruce Holst. Holst has called the gardens and labs at Selby home for 20 years.

In 1973, Dodson was named as the first executive director for Selby Gardens. The first two people Dodson hired were gardeners to help tame what had become an overgrown property. Slowly the staff grew to include a secretary and two doctoral candidates. The date of July 7, 1975, is cited as the official opening of the gardens; admission was $1.

Secrets to Selby

Pulling into Palm Avenue from Mound Street, visitors cross over a quilt of faded crimson-and-brown Augusta Block bricks — Selby Gardens’ own yellow-brick road of sorts. The gardens and property provide a snapshot of early 1900s Florida dripping with tropical foliage.

An hour before the gates open to the public, the gardens are abuzz with volunteers circulating with wheelbarrows filled with tools for their morning tasks. Across from the Christy Payne Mansion a group of volunteers are spotted along the administration building combing for weeds between trees and shrubs.

The gardens survive and thrive under the supervision of a staff of 46 employees and a network of 642 volunteers who contribute an estimated 61,000 hours per year. Volunteers perform tasks that range from laying mulch to serving as curators for the butterfly garden.

That tropical environment at Selby Gardens is maintained with the more than 20,000 greenhouse plants that include some specimens that have been kept alive for more than 40 years and come from the botany department’s various expeditions to exotic locations in Brazil, Belize and Ecuador.

“It hasn’t changed much in the scope of what it does,” says Bruce Holst, director of botany. “What has changed is that over the last 40 years, and in the 20 I’ve been here, we’ve added a tremendous number of collections to our herbarium and to our living collection. We’ve created a very, very rich environment to study tropical plants.”

This year makes the 40th year that Selby Gardens has been in full bloom. Events throughout the year will celebrate the milestone.

“While we are certainly a Sarasota treasure, our collection is actually at the world-class level of excellence,” Jennifer Rominiecki, CEO and president for Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. “We have scientists, researchers, botanists and horticulturists that visit us from all over the world because of the depth and breadth of the collection we have here.”

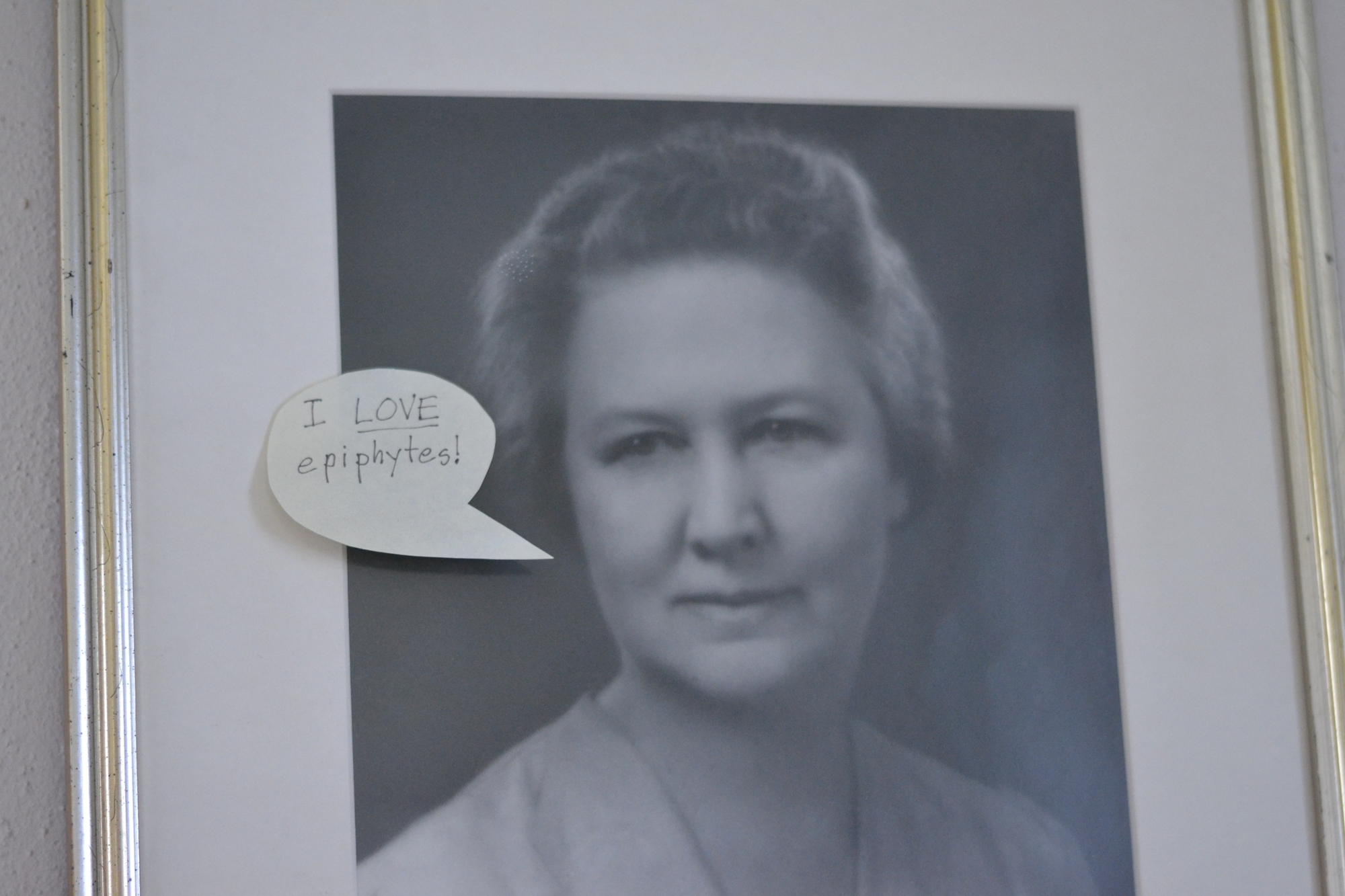

Portraits of the gardens’ namesake, Marie Selby, hang in virtually every building on the property. This includes the entryway to the horticulture building, where so much of the gardens’ reputation has been built through its work with epiphytes, long after Marie got a chance to see it blossom.

“Marie probably knew what an epiphyte was,” Holst said. “But she had no idea what the gardens would become.”