- November 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

While most beachgoers are still snug in their beds, some turtle-loving citizens are up at 6 a.m., walking the beach in search for newly laid sea turtle nests.

Longboat Key Turtle Watch volunteers repeat this routine every morning for six months straight.

Here’s what happened on a recent Tuesday morning, when we trailed volunteers.

Longboat Key Turtle Watch Vice President Cyndi Seamon, trained volunteer Terri Driver and friends Kayla Chatham and Mike and Victor Carrillo grab their bags, spray themselves with bug spray and head out to walk one mile down the beach.

These five volunteers aren’t the only ones on Longboat Key’s beach in the early morning searching for nests.

Turtle Watch, which patrols the Manatee County portion of Longboat Key’s beach, splits its territory into four zones, each approximately a mile in length, to look for newly laid nests and check previously marked ones.

This group patrols from the Covert Inn II in the 5200 block of Gulf of Mexico Drive and walks north to around the 6400 block.

At the end of the walk, they will report their nests or findings to Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium.

Seamon sets her alarm for 5:15 a.m., but she said she has an easy drive because she lives on Longboat Key. Some people drive from as far as Lakewood Ranch to attend a turtle walk.

Seamon and Chatham walk along the water looking for fresh turtle tracks and picking up trash that beachgoers left behind, while Driver and the Carrillos walk along the previously marked nests, checking their safety and markings.

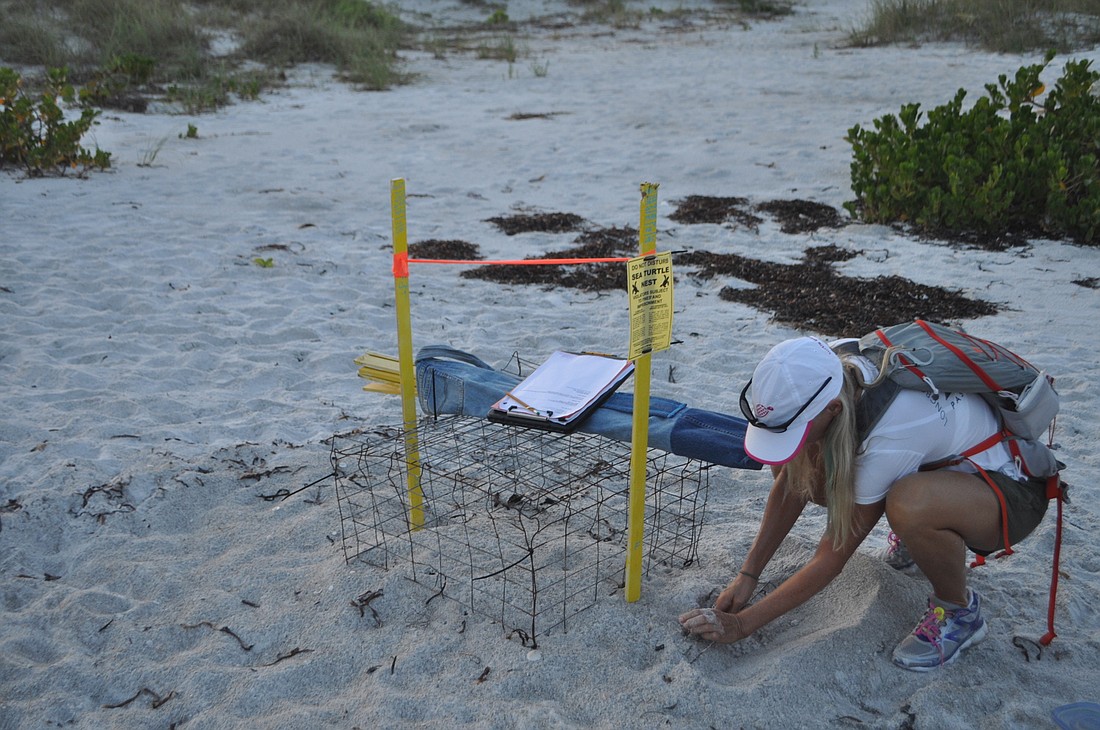

Volunteers sprinkle ant killer on one nest, while another needs its caging pushed farther into the sand to prevent raccoons from crawling underneath.

About halfway through the walk, volunteers notice fresh tracks in the damp white sand.

The tracks are deeper than usual, which could mean this turtle might have an injured flipper. The group follows the tracks but realizes no nest has been laid. They carry on despite the rising sun and heat.

Soon, another set of fresh tracks appears. Because of beach erosion caused by Tropical Storm Colin, turtles have to travel farther up the beach to find dry sand. Seamon said the nests placed at a higher elevation are more likely to survive another storm.

Driver begins scooping sand out of the way then gently tiptoes on the smooth sand to see if it is hollow beneath — a clue that eggs are hiding under there.

The first attempt leads to an empty crab hole, but on Driver’s second attempt, she finds an egg. She covers the nest again with sand and begins marking it with wooden stakes.

While Driver finishes marking the nest, an early jogger alerts Seamon that she thought she saw new tracks farther down the beach.

As the volunteers walk on, they recognize those tracks to be from the same injured-flipper turtle that left the tracks they discovered earlier.

However, these tracks have a large “X” through them in the sand, meaning the group walking the previous morning already marked her nest.

Chatham, a Lakewood Ranch resident, said her favorite part of volunteering is digging for the first egg when they excavate nests after they’ve hatched.

“It’s the hardest part because we can dig for hours,” she said.

It can be a time-consuming endeavor. That day’s one-mile walk lasted two hours; sometimes, the walks can go until 11 a.m. or noon.

But the rewards make up for the time commitment.

“I think we all make a little change in the conservation efforts,” Seamon says. “It’s a small part that we do, but it feels like if we all do it, it multiplies.”

Seamon says she has also made lifelong friendships and even found parental figures in some of the older volunteers, some of whom are their 90s but still make time for Turtle Watch.

Eggs take between 45 and 65 days to hatch. Seamon and other volunteers will check the nests until the eggs are hatched or for 70 days.

Although turtle nesting season officially ends Oct. 31, there have been years when Seamon is still checking nests in the middle of November.

The baby turtles that survive will have a long journey ahead of them.

“They make their way around Florida to the Gulf Stream to the West Coast of Africa,” Seamon said.