- May 10, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

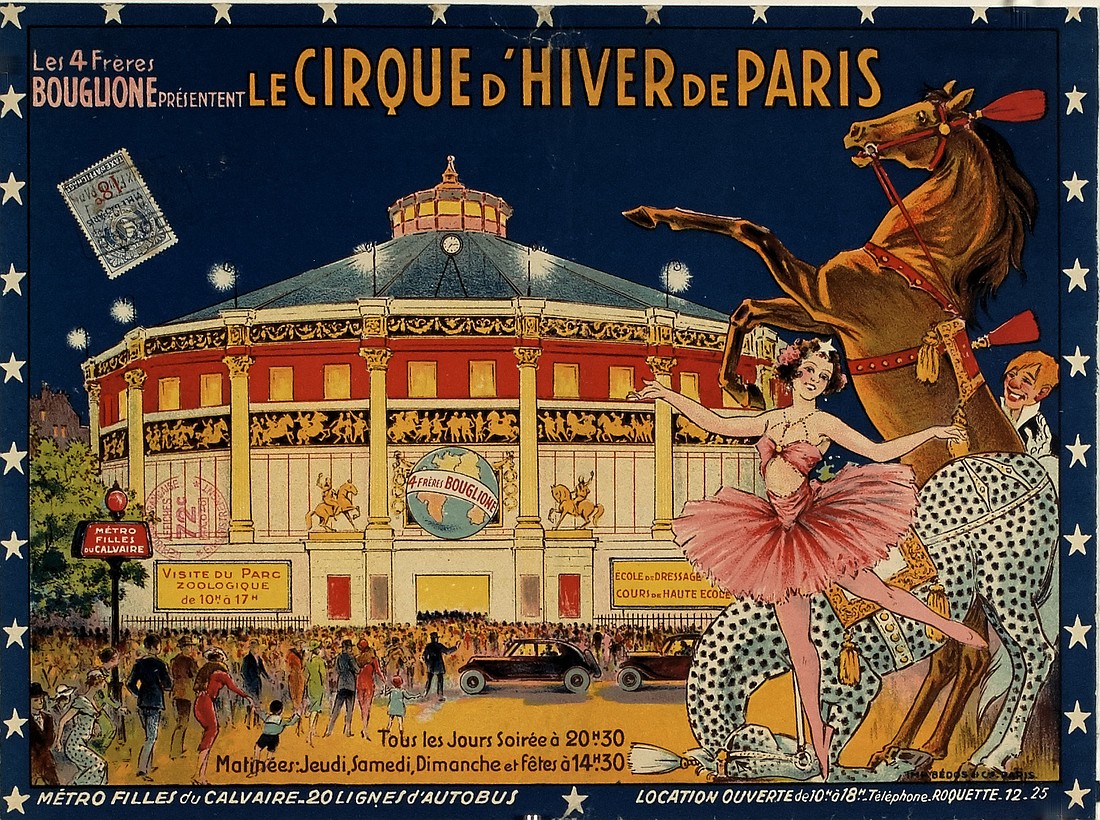

In art, there are some things that transcend language and culture — things that are universally understood. You don’t need to speak German, for example, to understand the imagery in Paul Gerin’s 1931 circus poster promoting “The Great Diving Ringens.”

In the poster, a crowd of spectators stands gathered around a small pool. High above, four aerialists are diving into the shallow water from an elevated platform. A larger-than-life skeleton peers out from behind the spotlight, poised to pluck the performers out of the air.

The poster is part of The Ringling Circus Museum’s new exhibition, “Cirque / Cyrk / Cirkus: Circus Posters Across Europe,” a collection of 30 French, British, German, Scandinavian, Russian and Eastern European pieces from the collection of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art and the Tibbals International Collection, and it’s a perfect example of the ability for promotional art to reflect the culture of its origin while transcending boundaries.

Kelly Zacovic curated the exhibition of posters, which span from 1905 to 1974 and have never before been displayed in a museum.

“It’s interesting to see how these European circus posters compare to American ones,” she says. “In Europe, the circus was largely stationary, and the acts would rotate, so the posters are usually advertising one particular act, instead of the whole majesty of the circus.”

The artwork also serves as a sort of anthropological study of the cultures from which the posters come.

For every flowery, ornate French flier, showing off the grandeur of the depicted circus acts, is an equally stark Soviet-era Russian one, hammer, sickle and all.

“They really look like propaganda posters,” says Zacovic. “And in a way, they were. At the time, the circus was run by the government, and it was the only approved form of entertainment. Before the revolution, the posters were much more ornate, but afterward, the tone completely changed. There’s this idea of the circus performer as the perfect Soviet citizen — hard-working, athletic and devoted to his country.”

The exhibition runs through June 20, and Zacovic says it’s a good opportunity for Sarasotans to learn more about circus history outside of American culture. Circus has its roots in Europe, and despite the differences, she says the art form is universal.

“Throughout the collection, there’s a sense of wonder,” she says. “Everyone wants to see something fantastic. The language is minimal on a lot of these posters, so you don’t need to know what it says to be pulled in by the symbolism and beauty. They’re more than just posters — they’re works of art.”