- November 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Tucked away at the end of Palm Avenue are more than 140,000 preserved remains of once-living beings filed away in a laboratory. Some float in alcohol-filled jars. Others lie pressed between the pages of books that discuss their anatomy. But they’ve all been kept from the public for decades. Until now, that is.

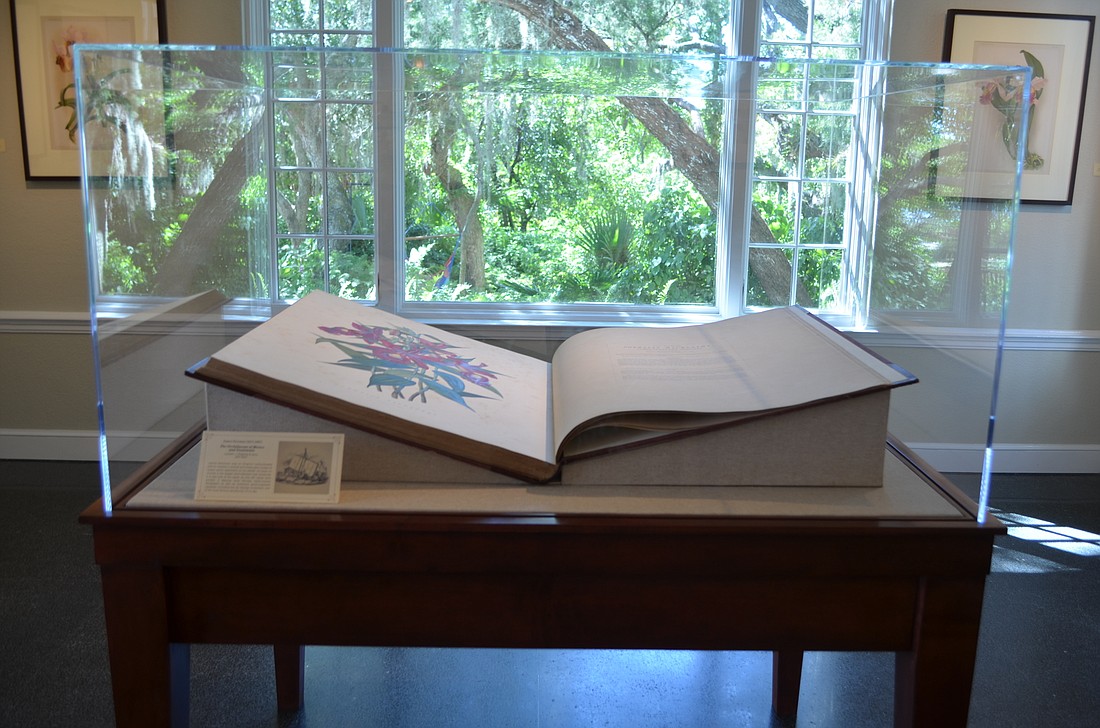

The Payne Mansion at Marie Selby Botanical Gardens now houses the institution’s newest exhibit, “Selby’s Secret Garden,” which offers Sarasotans a rare peek into the treasure trove of preserved plant and botanical art that Selby has accumulated in its 41 years of existence.

David Berry, the assistant director of academic affairs at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, was chosen to curate the exhibit. Berry has always fostered an interest in botany and the natural sciences, but his true asset comes from his graduate experience at Oxford University, where he researched the origins of museums, gardens and libraries.

Berry believes the exhibit is unique because it not only gives visitors the chance to view specimens and illustrations they might never otherwise see, but it also shows them that there’s more to a flower than its looks.

“I like the fact that the different materials being exhibited are all beautiful in their own way,” he says. “But they’re also tools of botanical research — it’s not just the beauty or the aesthetic quality. These have a role to play and a contribution to make to scientific discovery.”

Indeed, the 13 shelves of “spirit jars,” are beautiful. The specimens, preserved in an alcohol solution, sit on a western-facing wall of the exhibit room, catching the light in a way that causes visitors to stop and marvel. But upon further inspection, they learn more about the science behind the beauty. This slice of the world’s second largest spirit collection owes its splendor to a liquid preservation method used to maintain the specimen’s three-dimensional shape.

Organic Origins

Selby President and CEO Jennifer O. Rominiecki came up with the idea for the exhibit in summer 2015. After 10 months of preparation, it opened to the public Aug. 26, with the hope of exposing visitors to the research tools that botanists used throughout the

age of exploration in the New World.

“Google is more convenient,” says Mischa Kirby, director of marketing. “But the prints, drawings and herbarium specimens are still key parts of botanical studies.”

The tools Kirby references are what Berry calls “works of art in and of themselves:” botanical illustrations.

Selby’s vaults are home to more than 2,700 botanical prints and more than 500 bound volumes of rare books that date as far back as the 1700s. And they all contain this unique form of art — one that can only be done by artists who are trained to be scientifically accurate.

An art of Necessity

Local artist, writer and teacher Olivia Marie Braida-Chiusano is a prominent name in the world of botanical art, who opened The Academy of Botanical Art in 2004. She explains that the history of botanical art dates back before 30,000 B.C.

Without it, she says, ancient physicians couldn’t determine which plants were helpful to patients and which were harmful. The artform was thus created out of necessity, but has developed as a guide that both Victorian-era and modern botanists use to identify plants in the field.

“It’s the value of everything we come from and everything we’re going to,” says Braida-Chiusano. “What Selby is doing is contributing to the protection of our Earth.”

Berry notes that without plants, life as we know it would not exist. Plants are what sustains all life on Earth, he says, and it’s important for people to understand that in a time when our environment faces many threats.

He hopes working with Selby to tell its story in the most visually appealing way will help it achieve its ultimate objective.

“That is a fundamental goal,” he says. “To better understand plant life, and by extension, the role plants play in the world in which we live.”