- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It began as a pipe dream.

While viewing the documentary “Alive Inside,” Tidewell Hospice volunteer Chuck Cobb watched in awe as chords became catalysts. The film depicts patients with late-stage Alzheimer’s and dementia. They had withdrawn to recesses of their minds, and words couldn’t bring them back.

But music could.

By introducing the Music and Memory program, which was created in 2008 and uses music to access memory, patients were able to regain their identities. Cobb saw the program’s potential and vowed to start it at Tidewell.

“We just sort of laughed, because we’re a nonprofit agency,” Tidewell Director of Volunteer Services Stacy Groff said. “New programs are not easy to just find funding to start when you’re trying to exist on Medicare dollars.”

A musician himself, Cobb was determined to see Music and Memory work at Tidewell, but he didn’t live to see it come to fruition. He died in June 2015.

“We knew that flowers or a sappy memorial service … wouldn’t be what he wanted,” Groff said.

Using money collected in his honor, Tidewell became a registered Music and Memory hospice in late 2015. The hospice unveiled the program to its patients in June 2016.

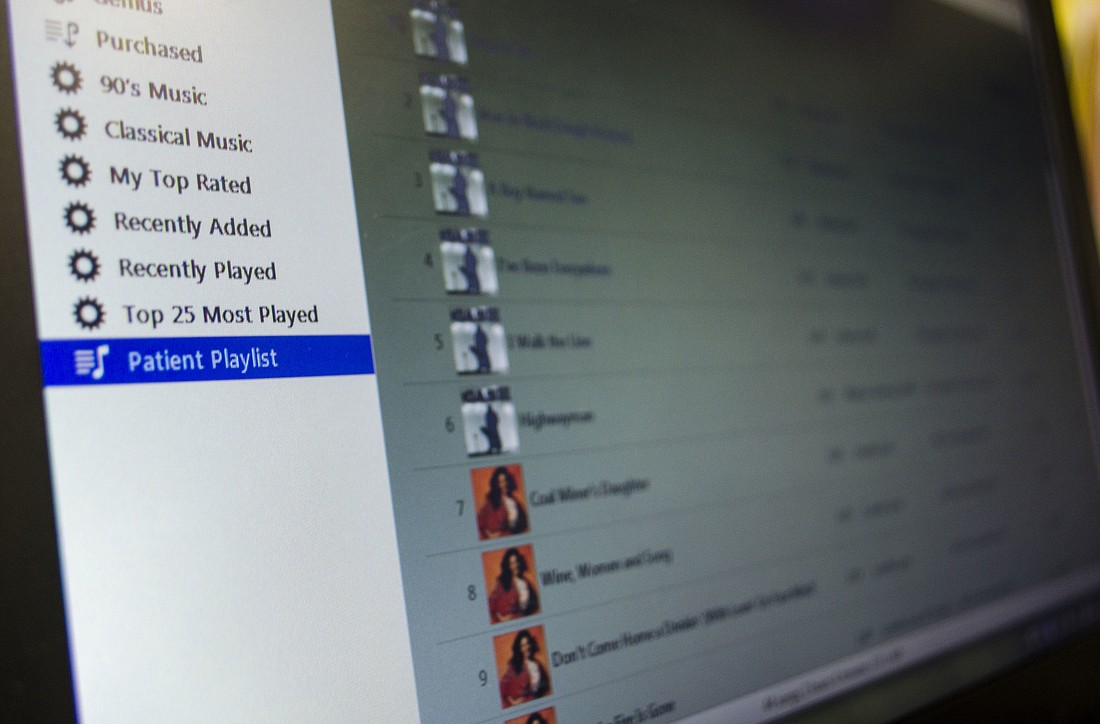

Equipped with 10 iPods, an in-house music library built from CDs and iTunes gift cards, nine volunteers are serving 23 patients in Sarasota and Charlotte counties. That’s just a fraction of Tidewell’s 1,000 patients. Although the numerical significance of the program is small, the emotional influence on the patients it serves is incalculable.

Diane McGaha has been a volunteer with Tidewell for two years. She decided to get involved with the Music and Memory program after seeing the impact of music on her previous patients.

One of her patients, a dancer in her youth, was wheelchair bound. Although she was relatively sedentary, Glenn Miller and his big band beats would make a connction

“When she hears a song she used to dance to … that gets her going,” McGaha said. “She sits in her wheelchair and she starts moving her feet ... like she is dancing with a partner.”

McGaha has a sense of what music will resonate with patients. Usually with older women, she defaults to the crooners, but trial and error has taught her that guidance is essential when trying to predict how people will react.

She once played Frank Sinatra on a visit with a woman.

Usually it was difficult to determine whether the patient was lucid, but this time McGaha could tell she was alert. In fact, she was visibly agitated.

“Her caregiver comes sprinting in from the back side of the building saying, ‘No! No! Not Frank Sinatra! She used to date him in the 1940s in California,’” McGaha remembered with a laugh.

Situations like that are why McGaha says the Music and Memory program is unique. It requires a caregiver or family member to fill out a questionnaire to give program administrators an idea of what musical era, genre and artist patients like.

McGaha has one patient in the Music and Memory program, but what she has seen in her visits has convinced her of the program’s power and potential.

The patient’s son said she loved Dean Martin because the Rat Packer bought her a drink in New York when she was young.

After an initial visit, McGaha came back with a playlist laden with songs from the King of Cool.

“I didn’t think it was going to be a good day,” McGaha said. “A lot of times she is just there with her head leaned over and her eyes closed. She is certainly not interactive.”

But by the 10th bar of Martin’s “That’s Amore,” McGaha’s patient wasn’t just awake, she was singing.

Sessions typically last between 15 and 20 minutes. The therapy isn’t restorative. There is no cure for late-stage neurological diseases. Yet, for those brief minutes while the music waxes and wanes, patients are transported — every downbeat a memory, every crescendo a reminder of their former self.

“It’s fascinating,” McGaha said. “Somewhere in the recesses of her brain it reaches a time in her life that she connects with still.”

Although the moments are fleeting, McGaha counts herself lucky to be present for them, and she hopes that as awareness of the program grows so will its resources.

For now, Tidewell’s small army of volunteers is using the resources they have to bring hope, one song at a time.

“For me, it’s just a privilege,” McGaha said.