- July 5, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

James Lecesne’s “The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey” is now illuminating Florida Studio Theatre. How to describe it?

A hopeful play about a hate crime?

A comic tour de force about a child murder?

That all sounds like perfect nonsense. But when you see the play, it makes perfect sense.

The title character is a 12-year-old boy. As the play opens, Leonard’s gone missing at a small town on the New Jersey shore. His mother-of-the-moment (a hairdresser who’s taken him in) pins a detective and makes him start a search. In the course of his investigation, the detective talks to various townspeople. Those interviews reveal the kid’s character.

Who is Leonard Pelkey?

For starters, he’s precocious, flamboyant, theatrical and openly gay. He plays Ariel in “The Tempest” and insists on fairy wings. Along with a college-level vocabulary, he’s an expert in cocktail dresses, mascara and costume design — and inventively glues a stack of amputated flip-flop soles to a pair of Converse All-Stars to create his own customized, rainbow-colored platform sneakers.

In Jersey, that kind of thing can be hazardous to your health. “Be yourself, but not too much” is the standard advice he gets.

But Leonard won’t back down and pays a sickening price for it. He finally turns up dead. And the search for a missing child becomes a whodunit.

That may sound like a large-cast production. But it’s really a one-person show.

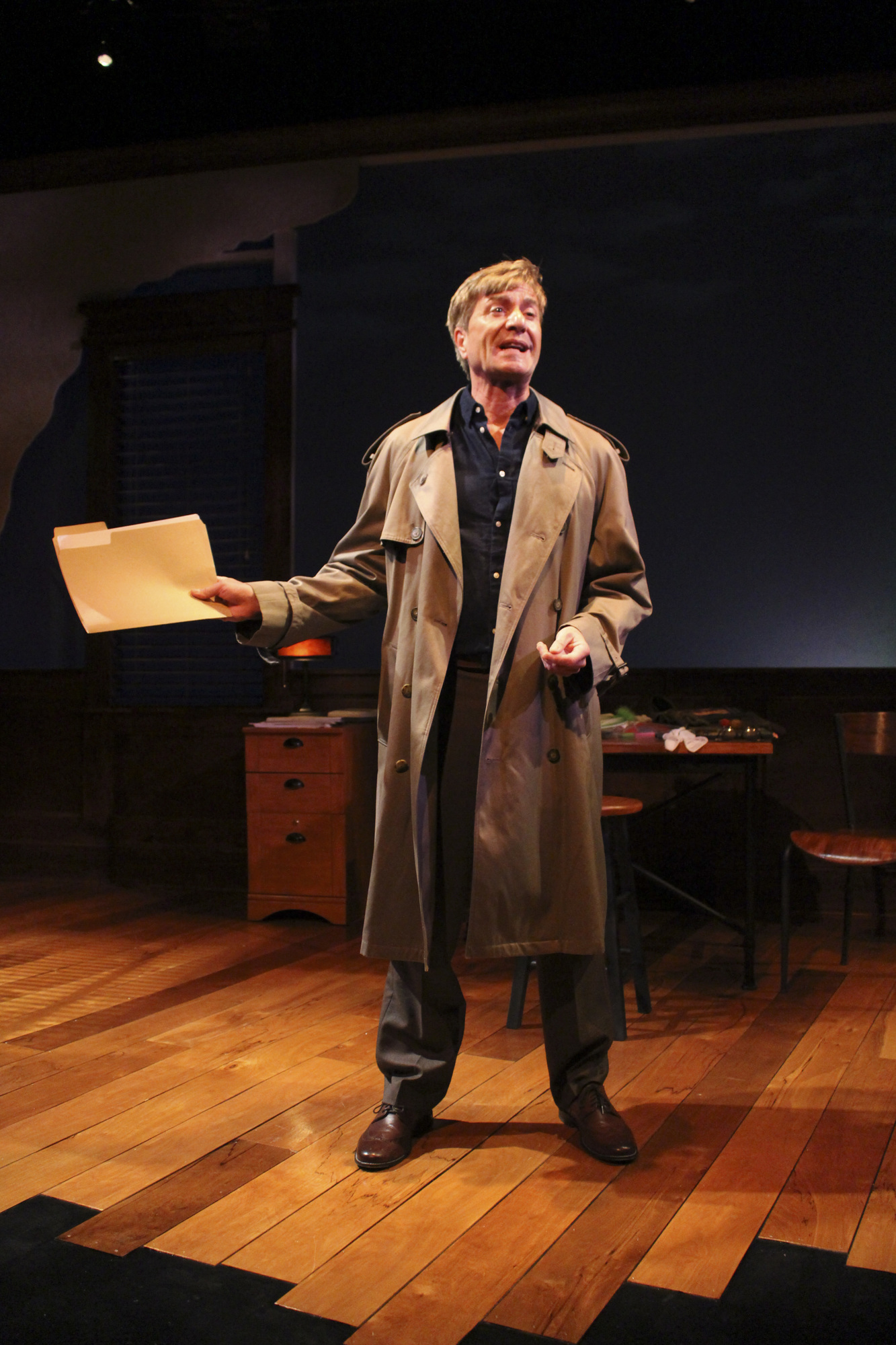

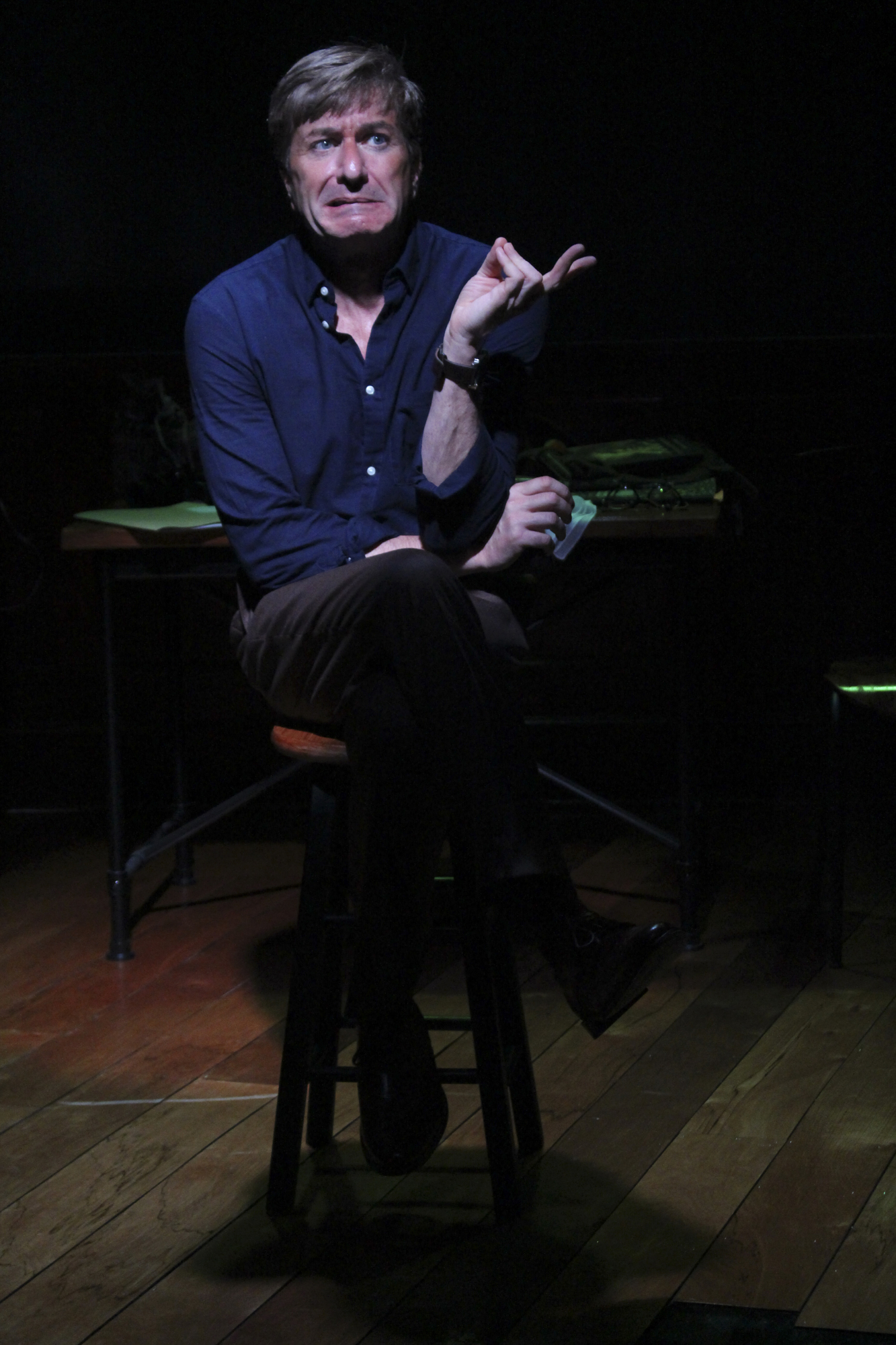

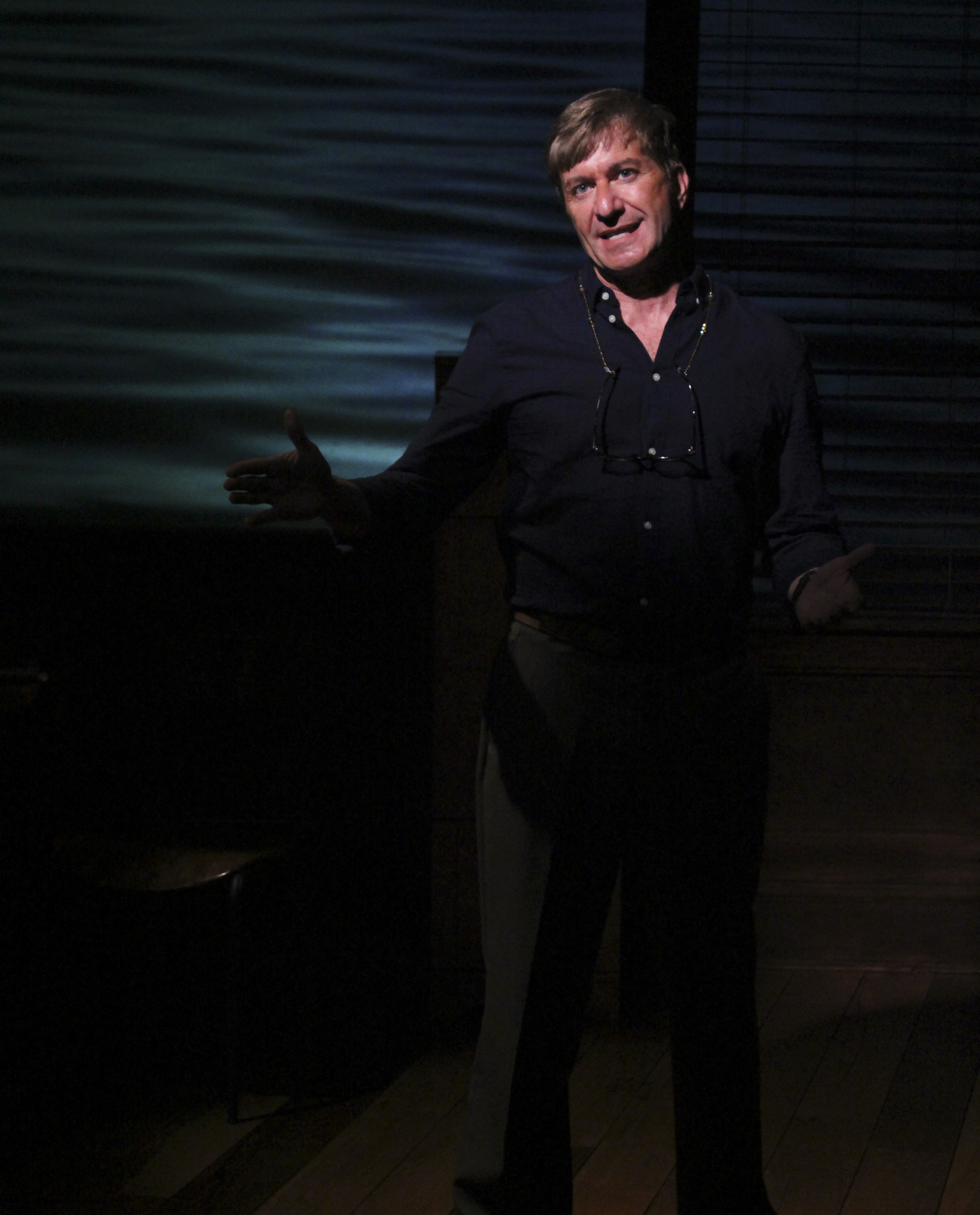

Jeffrey Plunkett morphs and mutates into nearly a dozen characters, both male and female. These include a hard-boiled detective, a shy teenaged girl, her in-your-face, beauty-stylist mother, the elitist British proprietor of a performing arts school for kids, a guilt-ridden German clockmaker, a mob-wife turned mob-widow and a snot-nosed, adolescent punk. Plunkett summons them all with rapid-fire shifts in body language and voice characterization. It’s a performance worthy of the late Robin Williams.

Strangely, Leonard is the only character you never see. He’s the central character. But you only hear about him through the words of others.

While the story is tragic, the tone isn’t. Director Kate Alexander honors the playwright’s intent and avoids a heavy-handed approach. Lecesne’s script is surprisingly comic—except for the few moments when it’s just not funny. Thanks to Alexander’s light touch, those gut-punch moments hit home.

The narrative unfolds in your mind’s eye and Stephen Dunham’s set — a battered, low-rent, utterly unromantic Jersey police station. He’s sliced away most of the back wall to reveal a rear-projection screen — replete with evocative Magritte-style images of blue sky and the props of Leonard’s brief life. (Excellent work by Mike Wood)

Adrienne Webber’s nondescript cop costume empowers Punkett’s chameleon-like changes.

Usually, what you see isn’t what you get. You’re thinking about the boy who wasn’t there. And what his loss means to the community, where Leonard’s absence is only starting to sink in.

People try to fill the empty space with chatter. Minimize it, downplay it and get on with their lives.

But denial is a flimsy strategy. The horror of Leonard’s death won’t be minimized. The memory of his life won’t go away.

As Joni Mitchell reminds us: “You don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.”

Now he’s gone.

And now they know.