- July 4, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

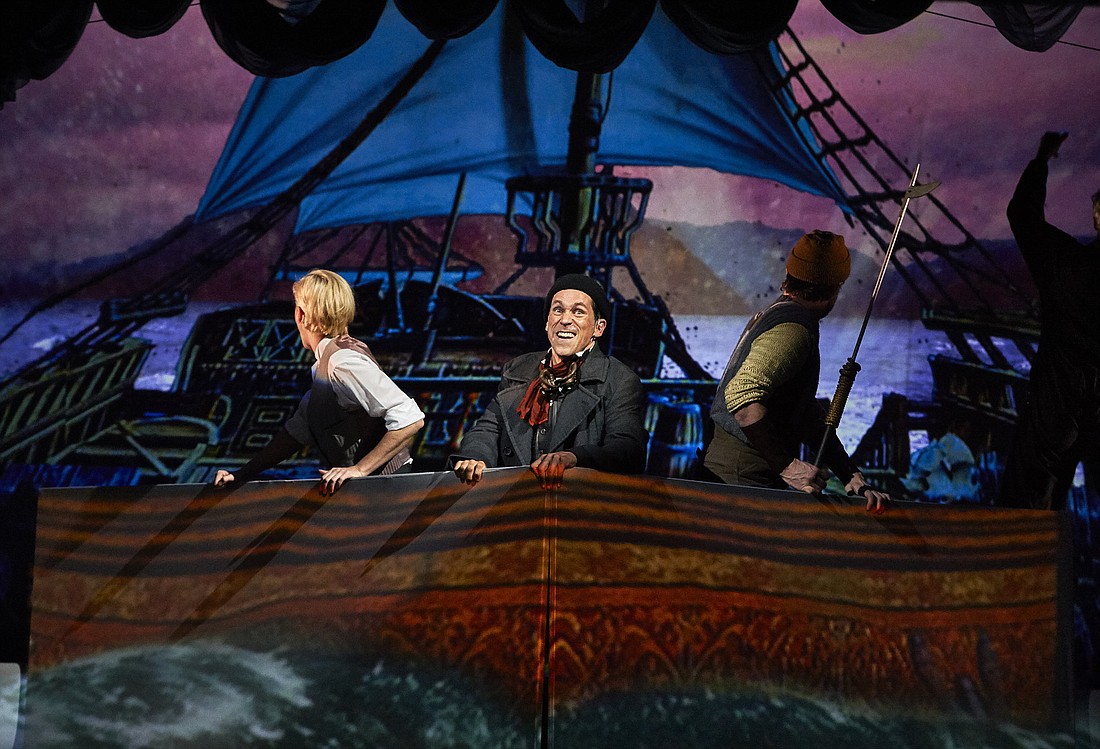

Some books lose their relevance almost from the moment they’re published. Jules Verne’s 1870 novel, “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” is one rare exception. His vivid accounts of the destruction of the life aquatic seem fit for the latest issue of Scientific American. His imagination was sprawling and prophetic, and until recently, I figured it would take director James Cameron, an army of film talent and an “Avatar”-sized budget to do the novel justice. But in 2015, Craig Francis and Rick Miller brought Captain Nemo to life with an immersive stage adaptation with dazzling high-tech props, projections, puppetry and toys. The interactive voyage continues through July 1, at Asolo Rep, directed by co-creator, Miller. He and Francis share their insights on this journey of the mind and senses.

Are both of you fans of Jules Verne’s original novel?

Francis: We’re both fans! Jules Verne does a wonderful job of combining science-fiction with adventure stories in his novels, which is why they’ve remained classics.

Pardon the understatement, but Jules Verne was amazingly ahead of his time. What are your feelings about the author?

Miller: I love speculative fiction, using the power of storytelling to take what’s around today and project it into the future. Jules Verne does this better than anyone, and he ignited my imagination as a boy.

Francis: It’s not so much his foresight that got me when I re-read the novel, it’s how timely it was: transatlantic communications; Charles Darwin; trying to reach the South Pole — these were ripped from the headlines in the 1860s. Jules Verne was the Michael Crichton of his time.

It’s a little-known fact that Captain Nemo (aka Prince Dakkar) was an eco-warrior, not a mad scientist, in Verne’s original novel. What are your feelings about the character?

Francis: We try to reclaim that aspect of Captain Nemo, and so does the modern character Jules in our version of the story. Nemo is indeed misanthropic. He left the world because he’s sick of oppression and war, and he’s promised not to set foot on land again. Some of his anger at what humans have done to the earth is justifiable, but as audiences will see, he can take it too far. Nemo’s a mysterious, volatile character, and that’s an edge we play with in the story: What is the line you cross from being an environmentalist to an eco-terrorist?

Miller: Nemo’s one of the most intriguing anti-heroes in 19th-century literature. In our show, we draw a parallel between Nemo and Captain Ahab from Melville’s “Moby Dick,” written 25 years before Verne’s novel. In our interpretation, Nemo thinks he has avoided Ahab’s fate by building his own perfect whale — The Nautilus, his submarine — and flowing freely within nature, not fighting against it.

How does your adaptation shine a light on the issue of the health of the oceans?

Francis: Nemo is out there in his Nautilus submarine, protecting the oceans, but we also acknowledge that in Jules Verne’s time, we thought the ocean was totally limitless, that we could exploit everything from it forever — and we can’t.

Miller: The play doesn’t dwell on eco-issues, but one of our first hooks into the story was that many fish that had been discovered in Verne’s time are now being driven to extinction. We take a modern water issue — the spiraling gyre of plastic in the Pacific — and use it as a parallel with the maelstrom that swallows the Nautilus in the novel.

Do people in First World countries tend to take water for granted?

Francis: Absolutely, and I’ll tell you a secret, Canadians waste more water than anyone on the planet. It’s the same issue, that because we have 20% of the world’s freshwater, we think it’s limitless.

Miller: People also think that because the oceans are so vast that we can throw anything into them, and it just gets washed away — but to where? The plastic in the Pacific is horrifying, but it’s also very distant and almost invisible, so it becomes someone else’s problem. We need to remind ourselves that water is the lifeblood of our planet. What we do to it, we do to ourselves.

Who are some of the influences of your creative staging? I’m assuming steampunk and graphic novels play a role.

Francis: We were influenced by them, for sure, but also by screens, which aren’t found in pure steampunk. Deco Dawson’s brilliant projections, and the sequences created by Irina Litvinenko with our team in Montreal, are colorful, hyper-real and stylized. At times, the visuals can feel like a storybook, a comic, or even a game.

Miller: We were influenced by the connection between stagecraft and shipcraft (rigging, hoisting, etc.), and also inspired by the flat sets used in theater in the 1800s. The sliding in and out of scenic flats suits this story.

Is the play set in the present or the past?

Francis: Both and neither! The play starts in the present, but we are whisked into Jules’s version of the story, which takes place starting in 1868.

Miller: It’s a bit of an alternate reality — Jules is speaking to the audience in the room as the narrator, but he also takes us back in time to meet his hero, Captain Nemo.

Why do mobile phones make an appearance?

Francis: Smartphones are these amazing communication devices we all carry in our pockets, but they’d be unimaginable to Jules Verne. Yet they still fit into the themes of Nemo’s rejection of civilization. We also expand on the story and themes in our Kidoons 20,000 App before, during, and after the show. When audiences pull out their phones at intermission, they can still engage with the story. Jules also accidentally takes his phone into the story with him, and its presence changes the story when Nemo ... well, come see it and find out.

I’m sure this play speaks to young people. What about cynical, jaded adults?

Francis: Actually, one of our hopes is to be a little less cynical. Our cast is amazing; the actors have brought a sense of playfulness and also richness to these characters. At heart, it’s just a really fun adventure story, and I promise you it won’t look like anything else you’ve seen this season.

Miller: Jules starts out as a cynical, jaded adult, unable to complete a Ph.D. thesis about collapsing ocean ecosystems. Where he ends up, and where we want to transport the audience, is a more hopeful place, where meaningful connection and action are possible. Part of that journey is discovering the power of storytelling and playful creativity, which kids naturally have, and adults naturally lose but theater helps them regain.

Have any actual submariners given you any feedback?

Francis: Actually, almost! At a preview, an audience member whose father was on a naval submarine said that the scenes aboard the Nautilus, and the brilliant ambient sound design by Richard Feren for the submarine scenes, actually evoked her childhood experiences.

Miller: For each production we’ve done, we’ve also connected with local scientists, oceanographers and marine biologists, and we’ve done that in Sarasota, too. We’ve partnered with Mote Marine Laboratory, South Florida Museum, Conservation Foundation of the Gulf Coast, and Sarasota and Manatee County libraries and schools to expand our outreach into the community.