- May 8, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

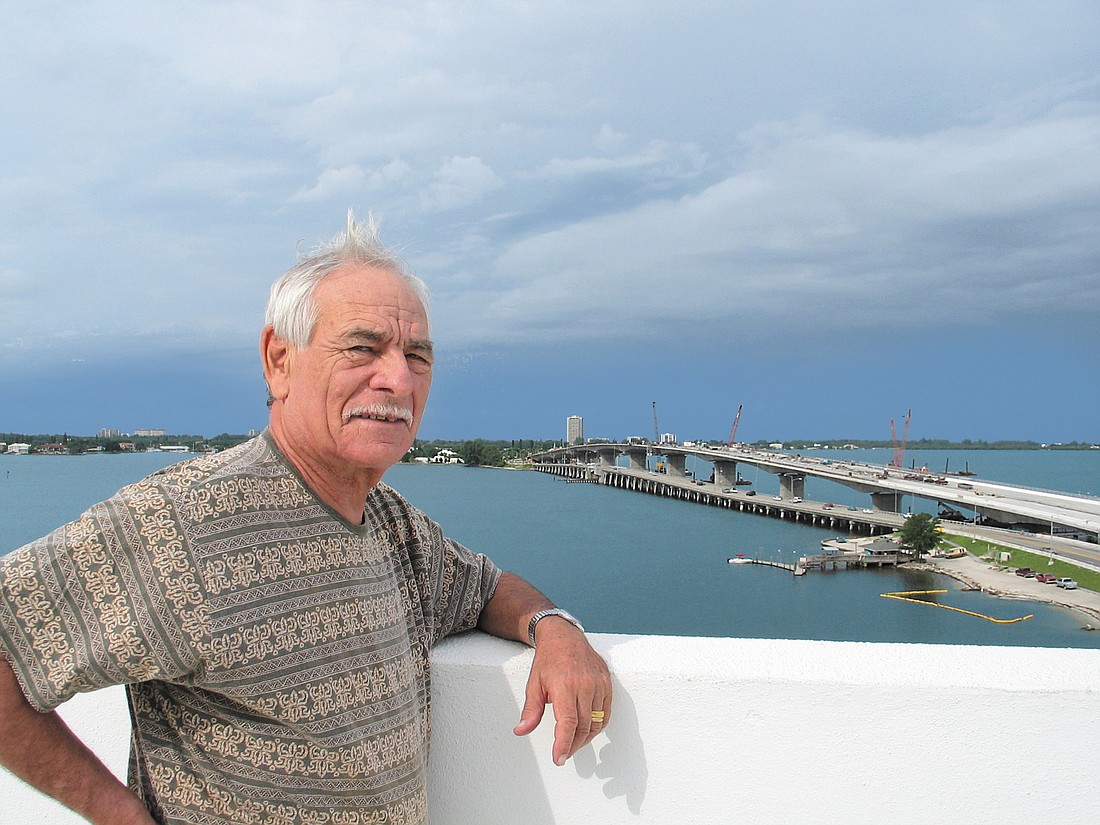

Gil Waters’ devotion to the causes he believed in helped build the John Ringling Causeway, spurred a crucial decade of growth in Sarasota and laid the foundations for a billion-dollar company.

Waters played a variety of roles within the community: reporter, business leader, city commissioner, developer, activist, philanthropist. No matter what he was doing, one thing never changed — his unwavering passion. That passion helped make Waters a key figure within Sarasota for more than six decades.

“Everything he did was due to helping the community,” said his wife, Elisabeth Waters. “When he saw something somebody needed, that was his drive.”

Gil Waters died Thursday. He was 90.

Waters grew up in Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York. A Yale graduate and Navy veteran, Waters spent his early years in Sarasota as a reporter for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune and at the head of his own public relations firm.

A 1957 meeting with local construction leaders steered Waters toward a new career path. In 1959, he helped found FCCI Insurance. Today, the company holds $2 billion in assets and employs more than 800 people. Until his departure in 1985, Waters pushed FCCI to pursue continued growth in the workers’ compensation insurance field.

Waters’ involvement in the business community also took on a civic bent. In 1958, he served as a member of the Volunteer Architects Downtown Improvement Committee, a group that recommended a series of projects designed to enhance downtown Sarasota.

In the early 1960s, he won a spot on the City Commission, which enabled him to implement some of those recommendations. That included the construction of the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall, the expansion of Fruitville Road and Ringling Boulevard to four lanes and the relocation of City Hall from the bayfront to First Street. Waters later described this period as “Sarasota’s decade of progress.”

In the '90s, Waters honed in on another major project he believed would benefit Sarasota: The construction of a fixed-span bridge connecting downtown to the barrier islands.

Today, the Ringling Bridge is an iconic piece of Sarasota architecture. But when Waters began his campaign, it was a divisive proposal with more detractors than supporters. When Waters solicited feedback on the idea via a newspaper ad, about 90% of the responses were negative.

That didn’t deter him. Waters had a notoriously blunt approach to communications. He was direct — which was occasionally a detriment to fostering a cordial working relationship with others, his friends and colleagues said. But by stating plainly what he genuinely felt, he also won supporters.

“He was effective because he worked with facts,” said Marty Rappaport, Waters’ co-chairman on the Good Bridge 2000 committee. “He did whatever it took to get the job done. He wasn’t bashful.”

His approach paid off. In 2003, Waters appeared at an opening ceremony for the Ringling Bridge, standing alongside city officials who had once opposed his vision. He wasn’t proud because he got what he wanted. He was proud because he thought the community got what it deserved.

“To this day, people come up to all of us and say we were right and the bridge is a success,” Waters said in a 2013 interview. “We, and the community, have been vindicated by our effort to get the right bridge in the right place.”

In 1994, Waters met his second wife, Elisabeth. Waters’ straightforward nature elicited different reactions from different people. For Elisabeth Waters, it was one of his most appealing attributes.

“He was a guy that never could tell a lie,” she said. “I think that really was the reason why I fell in love with him. He was the most bright guy I’ve ever met. I’ve never met a smarter guy than him.”

The couple was married in 1998. They traveled frequently, visiting every continent but Antarctica. At home, the two became active philanthropists and were fixtures at almost every gala benefiting the area's not-for-profit cultural, educational and social service organizations.

No matter what they did, or where they were, they remained by each other’s side.

“We were only married for 20 years, but we spent 48 hours with each other every day,” Elisabeth Waters said. “We loved to be together, to spend time together.”

Details regarding a celebration of life for Gil Waters are forthcoming. Until the end, his wife said he remained devoted to the things about which he felt passionately. A plan to build a pedestrian walkway connecting downtown to the bayfront was one of the final projects he advocated for, certain it would make Sarasota a better place.

Elisabeth Waters hopes it will still one day be built, a final piece of an expansive legacy.

“He would not give up,” Waters said. “If he thought something was right, he would do anything to get it going.”