- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Did you know that we just passed the unofficial holiday called “Ditch New Year’s Resolution Day.” Yes indeed; that two-and-one-half weeks into your New Year’s resolutions was Jan. 17.

Once this unofficial holiday was pointed out to me, I became somewhat obsessed with learning more about resolutions and how and when they work.

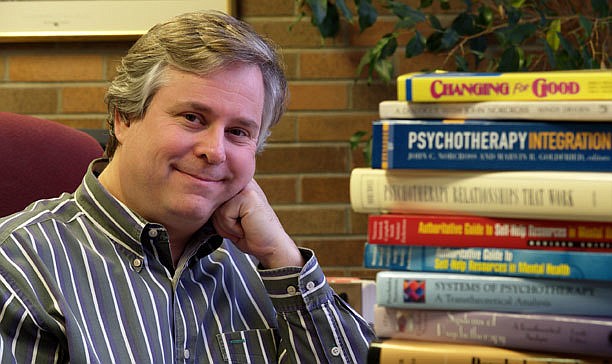

A Google search repeatedly brought up one expert’s name, so I ordered his book, “Changeology: 5 Steps to Realizing Your Goals and Resolutions,” and dove in when it arrived the next day. John Norcross, distinguished professor of psychology at the University of Scranton, has become the guru of change, and his tome is the bible on the subject.

It turns out that Norcross and his associates have done thousands of hours of scientific research on change, unlike most of the self-help books lining book stores shelves or listed on Amazon. In his introduction, he lays out the facts: “More than 75% of people maintain a goal for a week but then they gradually slip back into old behavior. However, research shows that almost all of the people who maintain a new behavior for three months make the change permanent; the probability of relapse after that period is modest.”

Ergo, his first “rule” is that in any resolution or goal, plan for working the changed behavior for at least 90 days.

His second rule is to be all in. As he says, “Bring passionate effort and confidence. Change is not a spectator sport.”

Norcross defines four clusters that characterize types of change to which people aspire. The first is the bad-habit category. We all know what that entails — all the excesses: eating, drinking, texting, whatever. The second is self-improvement. We want to land a more challenging job, learn French, hike the Appalachian Trail. The third cluster revolves around relationships — quarrel less with your teenage daughter, or spend more time with an aging parent. And the last cluster has to do with goals that transcend the former clusters. These are more spiritual: I want to be a better person, or understand what my purpose in life should be.

Incredible to me is his assertion that even though these four clusters cover disparate desires, the chops it takes to attack them are the same.

“The process of change is amazingly similar across diverse goals and problems,” Norcross writes. In the process of researching change, Norcross and his team have learned that people progress through the same stages of change for the 50-plus problems they have identified and studied. The same fundamental strategies work, and although the goals may be different, the journey to the goal is the same.

Trust me, I’m not going to give you anything but a small taste of what changeology is all about. I’m only just in the initial steps myself, but it is stimulating food for thought to ponder the steps.

Contemplation: We all recognize this stage. It’s when we step on the scales and experience that sinking feeling. Or, lay awake at night chastising ourselves — again — for getting into a disagreement with a spouse or friend. Typically, people stay in the contemplation stage for a minimum of two years, writes Norcross. The trick here is to avoid chronic contemplation and make a firm decision to take action.

Preparation: Here is where we begin making intentions and taking small steps toward action. This is where we prepare ourselves for making our New Year’s resolutions, for example. It’s an important step. In a 2013 study, some 60% of Americans in early December said they would make a resolution, but only 40% of them actually did by Jan. 1. However, those who did were 10 times more likely to succeed than those with the same goals who didn’t make a resolution.

Action: This is putting your resolutions or goals into play. You are, as Norcross writes, “walking the walk, probably after months or even years of talking the talk.” Accolades will rain down upon you. “You look fabulous,” or “I’m so proud of you,” etc. etc. However, the HUGE mistake here is that this is not the end of the journey. Anyone who has lost weight and then gained it back will relate to this, as will people who have quit smoking dozens of times, thought they had it licked and lit up “just one for fun.”

Maintenance: This is where the rubber hits the road. It’s all about continuing the change. Stabilizing behavior change and avoiding relapse is what maintenance is all about.

Really?

Anyone who thinks that change is easy is sadly mistaken. But, as a friend once opined when I was frustrated about a change I was attempting to incorporate into my life, “Anything worth doing well is going to be challenging and most likely difficult.”

And forget about perfection. When “resolvers” slip up, they often wind up committing what’s called an “abstinence violation,” Norcross said in an interview in the Wall Street Journal.

“If you stayed on budget for six weeks and then you violated the goal, you might say, ‘I blew it, I’m done,’” he says. That’s the wrong approach. “The way you respond to that first lapse profoundly influences whether you’re likely to get back on the horse.”

The key is to not turn a violation into a catastrophe. Go easy on yourself and don’t view six weeks of changed behavior as a waste. That’s when “they go from a slip to a fall,” he says. Here is the correct approach: If you view that it’s human to mess up and decide to recommit, the results can be astounding.

“Turns out the slippers are more motivated after the slip,” Norcross says. “It was a wake-up call.”

The key is to not give up, even with a slip or two. We get better at achieving our goals with time. “Some people call that optimism. I call it persistence,” Norcross says.

Kristine Nickel is a marketing communications consultant and former marketing and public relations executive. For more than 30 years, she has relieved her stress by writing features for publications across the country.