- July 11, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

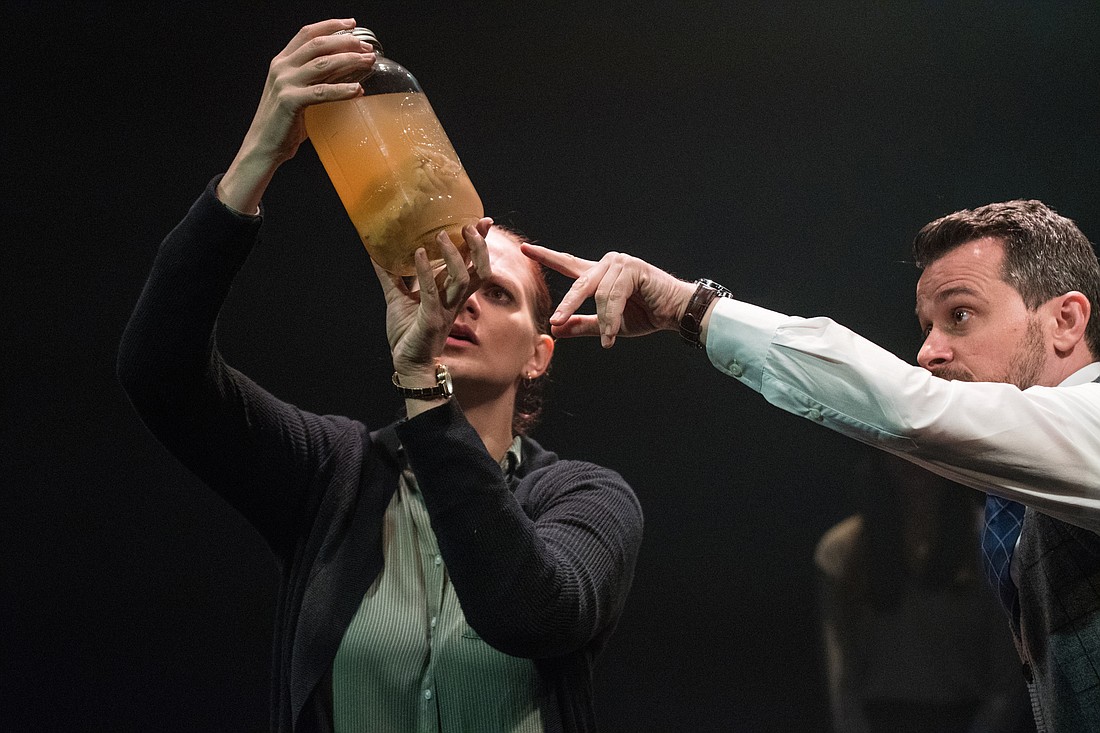

Nick Payne’s “Constellations” explored the implications of the multiverse theory earlier this year at Florida Studio Theatre.

With “Incognito,” the playwright shifts his focus to the universe of the human mind. It’s the latest production at Urbanite Theatre, and it’s been on director Daniel Kelly’s mind. He was happy to share his thoughts.

It’s a web of three interlocking narratives. Each story deals with a different aspect of the brain and human consciousness.

It’s the strange tale of the man responsible for Einstein’s missing brain.

Dr. Thomas Harvey. He was the Princeton pathologist in charge of Einstein’s autopsy. He took the opportunity to acquire Einstein’s brain. In Dr. Harvey’s defense, he felt he was within his legal rights. Einstein wanted his body to be cremated. He’d stipulated that in his will, but didn’t specifically mention his brain or eyes.

In Dr. Harvey’s defense, he felt he was within his legal rights. Einstein wanted his body to be cremated. He’d stipulated that in his will, but didn’t specifically mention his brain or eyes. (Marty: Actually another scientist took his eyes. Keeps them in a safe depository box. Seriously, the more you read about this stuff the weirder it gets.)

The human mind is the next great scientific frontier. Dr. Harvey wanted to be a pioneer. Einstein had mapped the laws of the cosmos. His goal was to map out the human brain in the same way.

No. Dr. Harvey was a pathologist, not a neuroscientist. He wasn’t really qualified, but he saw himself as a gatekeeper.

It’s part of the playwright’s investigation of our sense of self. Einstein’s brain defined Dr. Harvey’s identity. Without the brain, he was nobody.

Not all of it. There are portions of it around the world, but the majority is still missing. The legal battle for the fragments is ongoing.

It’s also based on a real individual, Henry Molaison. Medical textbooks referred to him only by his initials — “HM.” He’s the most studied man in science. He suffered from terrible seizures. At about the age of 27, he volunteered for an operation that removed portions of his hippocampus.

Yes, from today’s perspective. This was back in the 1950s, when altering the brain to deal with mental issues was really in vogue. The whole field of neurosurgery was exploding. The scientific understanding behind it was still primitive. I should add that it was elective surgery. Henry had a sense of the risk he was taking. He was willing to take that risk to relieve his terrible seizures.

He went under the knife right after his honeymoon. After the surgery, his seizures decreased. His intelligence and speaking ability were fine. But he’d lost the ability to create any new memories. If you spoke to him, he’d reintroduce himself every 30 seconds.

Yes. He’s very similar, aside from the fact he wasn’t trying to solve a murder. He was an agreeable individual, and easy to work with —the perfect subject to study. For brain science, he represented an incredible opportunity. His tragedy ultimately helped people.

It’s completely fictional—and it revolves around Martha, a present-day clinical neuropsychologist. She’s just adopted a new patient—a young man who’d been found beneath a bridge. He calls himself “Anthony,” but nobody knows his real name or origin. His real history is unknown—but he’s continually inventing that history. He might ask, “Have I told you about Deborah?” Then he’ll go on and on about “Deborah” in great detail. It’s hyper-specific information—and he’s making it up on the spot. It sounds like truth-telling—but it’s not. Martha theorizes that he is inventing memories and history to cope with some form of brain trauma, but we can’t know for sure. We then follow her struggle with her own identity as she starts to date a young woman after being married for twenty-one years to a man.

No. It’s a process called “confabulation.” Anthony’s suffering from total amnesia. He’s constantly inventing his past, because the human mind can’t function as a blank slate.

Exactly. Confabulation is one response to tragedy or massive physical or emotional trauma. In order to cope, the brain starts creating false memories. The brain is basically saying, “I can’t handle this”—and creating an alternate history that it can cope with, emotionally.

Payne is fascinated by the way the brain puts the flood of sensory data together to create the story of experience. He structured the play to echo that process. It’s really fractured from scene to scene. It’s challenging to follow, and he wrote it that way intentionally.

I have to walk a fine line. I try to give people a fighting chance to figure out the storyline. I make it clear — but not too clear. That demands a clear understanding on my part.

I did my homework! I had to isolate each single character, from scene to scene. Then I looked at how they and moved through time and related to each other. It’s a deductive process of isolating every character and scene. I know that this scene informs that scene. If Character A is lying, that colors my interpretation of Character B’s actions in the related scene. To keep it clear in my mind, I drew lines between various characters to clarify the connections … and I wound up with something resembling a detective’s evidence chart.

It’s a mess! But piecing it all together is fun.

That varies. Four actors play a total of 20 characters speaking six different accents and dialects, appearing in 31 different scenes. Each actor takes a different approach to their characters. Some work outside-in: Their posture and other physical choices inform them. Others work inside-out: They start from a sense of the characters’ thoughts and backstories. With either approach, there’s a lot of accent work—and keeping the accents distinct is a challenge. Fortunately we’ve been able to work with a terrific dialect coach, Kris Danford.

Right. From a directorial standpoint, it’s tough. The actors have to create 20 unique, distinct characters. I have to make sure the audience can tell them apart without descending into total farce where actors are grabbing hats or ties to telegraph their different roles. Yes, it can be difficult to follow. As I said, from the playwright’s viewpoint, that difficulty is essential to the story.

Choosing one version of the story I’m telling, and that’s a collaborative effort, informed by the decisions of the actors. There are many possible choices. But for the sake of sanity, I have to choose the version I find most compelling. Another director might make a vastly different choice. But I can’t direct multiple versions of the play; I can only do one. Ultimately, each audience member has to make their own choices and piece the story together for themselves.

My take is that Payne is in awe of the mysteries of the human brain. It’s as if he’s saying, “Look at what this three-pound piece of flesh is doing!” The brain is a storytelling machine. We’re only picking up small bits of information. Somehow, the brain fills in blanks and creates our awareness of space and time. How it accomplishes this is still largely unknown. The playwright isn’t trying to solve that mystery. Payne celebrates the mystery, and I think that’s the point.