- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

“For the strength of the pack is the wolf, and the strength of the wolf is the pack.”

It’s both “The Law of the Jungle” (a poem in “The Jungle Book” by Rudyard Kipling) and adapted as the “Law of the Pack” taught to every child who becomes a Cub Scout. It also turns out to be a great metaphor for the performing arts.

“We’re all stronger together,” says Asolo Repertory Theatre’s “Jungle Book” Co-Creator and Co-Director Craig Francis. “That works for Scouts but it also works for theater companies — we’re trying to create one magical experience for people who come to see theater.”

Francis and Rick Miller, co-creators of last year’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea,” are back with Asolo Repertory Theatre this summer for the world premiere of “Jungle Book.”

This adaptation of Kipling’s beloved classic uses a cast of four and a unique multimedia approach to set design that modernizes the tale, Francis says.

And though the actors must play several characters, they wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I think you’re able to develop deeper relationships because there’s only three other people you’re in constant contact with,” actor Anita Majumdar says. “With a small cast there’s a real sense of connection and trust that develops.”

It takes work to find actors who gel onstage, but even more importantly, strong actors who could wear a variety of hats (or masks and hooded animal jumpsuits, rather).

“It was important for us to find good chemistry — there’s no weak link,” Francis says. “With a cast of this size, there can’t be Joe at the end of the chorus line who never kicks on time.”

Actor Matt Lacas, who more often performs in large-scale musicals, says the smaller cast holds him accountable. If he messes up, he knows he’ll be caught.

Cast member Anita Majumdar is quick to agree, but adds that this sense of accountability is more of an internal struggle. She calls the cast radically forgiving, so even though she fears one misstep will have a negative domino effect for everyone, the other three move on without giving mistakes another thought.

Along with the challenge of limited scene partners is the use of several props and multimedia requiring its own choreography. It’s a delicate dance, juggling several props and more than three roles without any real down time.

“As soon as that curtain is up, it’s 65 minutes of go, go, go, go,” says Lacas.

Majumdar agrees. This isn’t the type of show where you can check Facebook during the scenes you’re not in, she says.

“We use a lot of the tricks in the theater bag,” Lacas says. “Like, we turn into a car in one moment and it’s just so simple and so magical at the same time because of two props.”

The projection work in particular presents a challenge that isn’t visible to the audience. Majumdar says the rear projector is so large, she has to choreograph her own movements to stay out of its way when getting on and offstage.

“In order not to be seen and to make our next entrance, we’re constantly ducking underneath,” she says. “I have a dance background so I have to treat it like dance … It’s really just a full rotation. I’m onstage and I ended up here and now I exit, and it has to be seamlessly treated as part of the performance.”

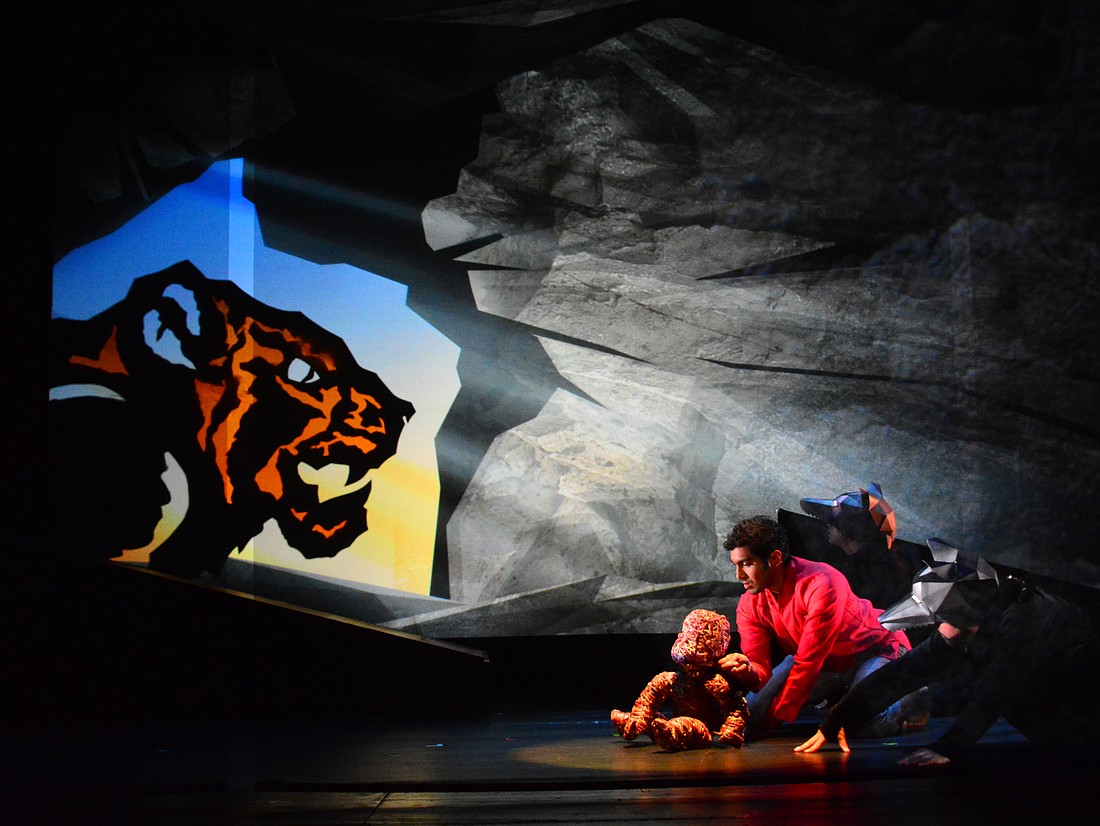

It’s this continuous motion that seems to be a theme of “Jungle Book,” during which actors are either onstage performing or backstage getting the appropriate mask, preparing a shadow play apparatus or interacting with another form of media.

Francis says he, Miller and Scenic, Prop and Costume Designers Astrid Janson and Melanie McNeill chose not to include a single leaf or other jungle-related 3D object in the show’s aesthetic because using multimedia makes it more immersive. Instead, they rely on Multimedia Designer Irina Litvinenko’s use of engaging video and interactive technology such as projections, silhouettes and animations to set the scene.

“We want people to feel that they’re seeing something different and getting a window through this character Mowgli into another world — and maybe looking at their own world a little differently when they come out,” Francis says.

The effect is a contemporary take on an old story that makes it more relevant to modern audiences of all ages, Majumdar says.

“It pulls it toward 2018,” she says. “It’s not something to forget about — it actually implicates us and our relationship to the environment and how we’re fast-tracking to becoming the Everglades again. And that’s not just for Florida, that’s a global story.”

It’s this environmental call to action that made the idea of modernizing “Jungle Book” intriguing, Francis says. But they’re also staying true to the book by telling the story through both the animals Mowgli interacts with in the jungle and the humans he lives with in the town.

“They’ll see the pieces they know and love treated in a completely different way, and then they’ll see more of the story that they’ve never seen before,” Francis says. “We want to give people that essence of what they love and then show them more.”

The co-creators also added their own lyrics and poems, and gave Mowgli a sister, Maya, because they felt the story needed another strong female character — especially because most Victorian-era writing features few female characters.

“All of the female characters in this show cannot only save themselves, they can kick butt,” Francis says. “And that’s important.”

When all these moving parts are put together, they ask the audience a big question.

“How do we coexist in one environment together?” Majumdar says. “Our relationships to animals is in this constant state of resistance and the play advocates for finding a way to work together.”