- November 23, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

At first glance, the photo isn’t alarming. The image of two men standing on a dirt ledge above a woman with her arms outstretched isn’t quite out of the ordinary — we’re used to seeing men depicted above, or subtly dominating, women in popular imagery.

But when viewers look again, they might notice the woman’s arms are reaching up so she can climb up toward the men, one of which is holding a rope that appears to be pulling her up. Or dragging her.

The visual in question is one of many digital prints by conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas now on display at The Ringling’s Keith D. and Linda L. Monda Gallery of Contemporary Art. It’s an image that was originally part of a Drummond sweaters advertisement, which featured a paragraph starting with: “Men are better than women! Indoors, women are useful — even pleasant. On a mountain, they’re something of a drag.”

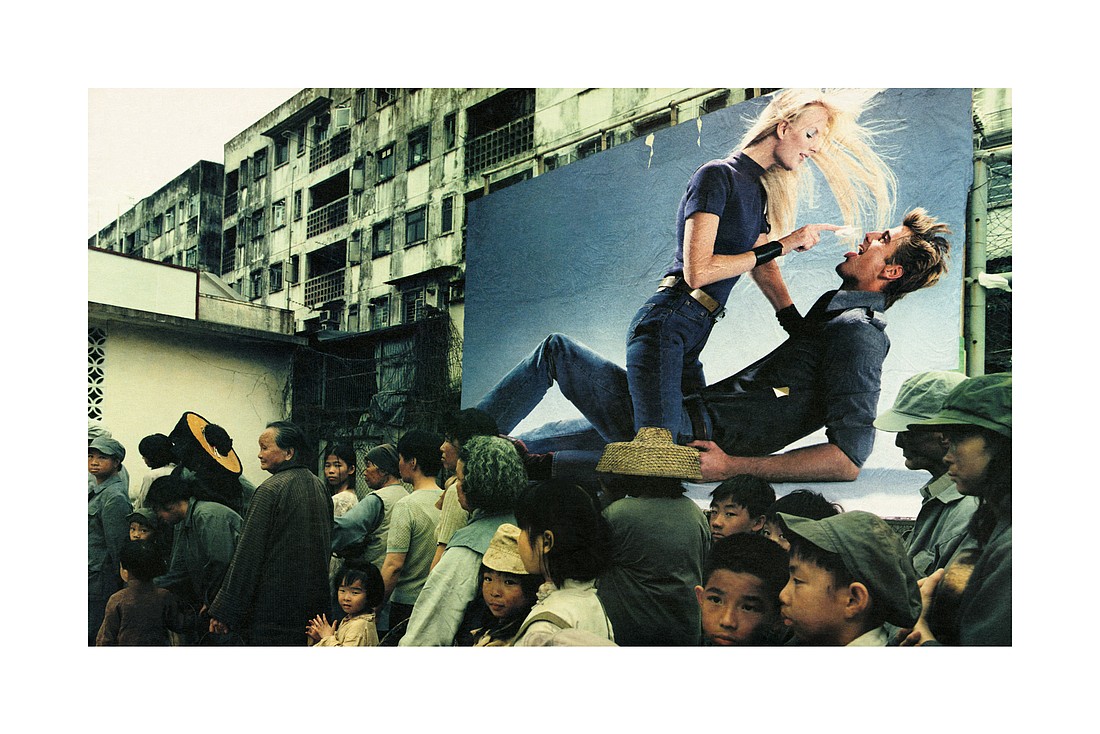

By removing the text from advertisements, the exhibit, “Hank Willis Thomas: Branded/Unbranded” examines how marginalized people have been represented by imagery in advertising and what that says about the prejudices ingrained in modern culture.

“They’re selling stereotypes,” Christopher Jones, curator of the exhibit, says of the ads on display. “But our perceptions of ourselves change.”

Thomas’ work is informed by his own experience.

When Thomas was around 5 years old, he became fully aware of his racial identity as an African-American. It was around the same time that he began paying attention to advertisements.

“For me, that’s the moment you start to recognize yourself as part of a larger world,” Thomas says. “You start to learn social codes.”

In the early 2000s, he started piecing together the puzzle of branding in relation to personal identity and realizing the influence that marketing tools have on shaping individual identities.

He decided to use art to critique and show the underlying truths of these ads.

“Truth is better than fiction, so rather than making images myself, I used actual ads,” he says.

Visitors to the exhibit are greeted by a large neon sign that reads “It’s Everywhere You Want To Be The Life You Were Meant To Live,” which is a combination of the slogans for Visa and Caesar’s Palace Hotel in Las Vegas.

The pairing of the slogans signal the tone of what’s to come in Thomas’ exhibit.

The exhibit on display is composed of three of Thomas’ series, each examining a different aspect of advertising and identity.

To their left upon entering, visitors will see the first, a series of Photoshopped images that are some of Thomas’ earlier works, part of the “Branded” section of the exhibit. These pieces utilize physical and figurative representations of branding, perhaps the most powerful of which is “Scarred Chest,” a manipulated Nike ad in which the athlete’s chest has been physically branded with Nike logos.

Jones points out that this image is particularly potent because, like many athletic brand ads, the model is African-American, and American slaves were often physically branded as a form of punishment for running away throughout America’s slavery era.

The curator says this image gained attention when it was released in 2004 because of its raw, striking nature that forces viewers to face the fact that African-Americans are often marketed in terms of their stereotypical athletic prowess and general physicality.

Slavery is also alluded to in “Football and Chain,” a Photoshopped image of an African-American football player trying to run with the ball but chained to a down indicator. Jones says Thomas uses references to not only popular brands but popular pastimes such as football to reach more viewers and spread his message through an iconic element of American pop culture.

The remainder of the exhibit focuses on a sampling of works from two of Thomas’ other series. For “Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015,” Thomas created a set of 100 prints spanning the past 100 years that focus on advertising imagery involving white women.

His other series, “Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008” features two advertisements from every year between the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and Barack Obama’s 2008 election as president.

Although the two series focus on different groups, in both, Thomas achieves his effect by removing the original text that appeared on the ads.

When the ad is stripped of its copy, viewers are forced to analyze the image itself — and they would never guess what product it’s meant to sell half the time, Jones says. With a naked image, the subliminal message being sold becomes clear.

For the series on women, that message is a string of perpetuated stereotypes of white women in the U.S.

In the other, guests get a look at many of the most disturbing and fascinating images depicting people of color during a 40-year period, all of which are meant to show how the offensive imagery reaffirms and reinforces stereotypes about African-Americans, Jones says.

“You can see these depictions of who we are according to these corporate agendas, and how that changes over time,” Thomas says.

In both series, the ads reflect how social norms and views evolve over time.

For example, the exhibit on women begins in 1915, at the start of the women’s suffrage movement. Thomas altered one advertising image from each year of this period, and The Ringling has 11 on display (almost one from every decade).

Jones notes this period got particularly interesting around WWII, when women joined the workforce to make up for the lack of men in industry jobs. Women’s role in society changed at this point, yet marketing materials didn’t often reflect that.

“These marketers were thinking about what women want,” he says. “Conversely, they were asking women to reinforce assumptions about themselves.”

This becomes particularly evident in pieces such as the chilling “House rules!,” which was originally an ad for a men’s pants brand that features five men grabbing and laughing at a woman who is only wearing her underwear.

Jones notes that today, this seemingly violent image would immediately register to viewers as assault, but when it came out in 1967, it was perfectly acceptable.

This exhibit doesn’t contain particularly new work of Thomas’, but it’s unique in that the artist lent The Ringling several of his original ads from his personal archive that he used for the appropriated images on display. Thus, visitors will get the chance to see the original text and gain more context for the imagery before or after they see Thomas’ version.

And they’ll be the first to do so, because this is the first time these original ad copies will be on exhibit anywhere.

The ads will be in glass cases in the middle of the room as to not interfere with the works hung on the walls of the gallery, and visitors have the freedom to refer to them in their preferred order.

“We wanted people to have as much of an experience with Hank’s work as possible,” Jones says.

Thomas says it’s critical for consumers to analyze and engage with marketing materials.

“I really hope that guests leave with a more critical eye and a greater capacity to gain agency from brand narratives,” the artist says. “They (the ads) tell them who they are and who they’re supposed to be ... I hope they don’t feel like they need to automatically identify with it.”