- June 15, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

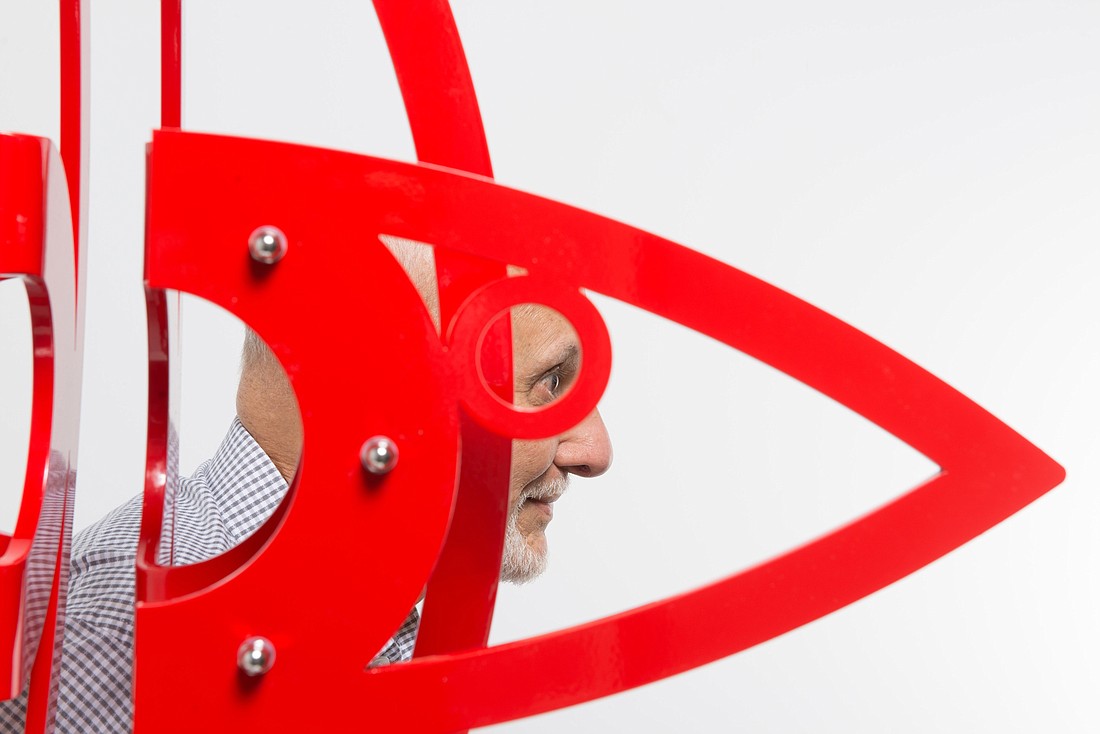

Some people see a mattress on the floor of an art gallery and immediately see a political statement. Others might tilt their head in confusion, furrowing their brows while searching for what must be a hidden message. Abstract artist Jorge Blanco just gets sleepy.

“That doesn’t work for me — I need to feel something,” Blanco says of artwork like this. “When a piece of art needs a lot of explanation, it’s not right to me. Art is about feeling.”

Blanco keeps things simple. His fun, vibrantly colored sculptures aren’t meant to inspire deep contemplation. Instead, his goal is to communicate happiness.

Or, as his website describes it, he creates “soaring testaments to the optimism of everyday life.”

Now, he’s sharing his work with local art lovers at his Alfstad& Contemporary solo exhibit.

Blanco says that, like most kids, he was constantly drawing throughout his childhood. From mindless doodles to meticulous copies of his favorite published comics, Blanco was always creating something.

His family home had no art on the walls, Blanco says. But when he walked into his best friend’s bedroom at the age of 12 and saw an abstract painting for the first time, he was mesmerized.

Immediately, he felt an urge to create abstract art.

As a young adult, Blanco studied industrial design on scholarship at Neumann Institute of Design in Caracas, the capital of Venezuela. He says design was the preferred route to take rather than painting because in Venezuela, painters can’t make a living from art. Design, by contrast, offered him a more lucrative avenue.

He then spent several years studying sculpture at Rome’s Academy of Fine Arts, where he was influenced by the classic art surrounding him, but also the terrorism happening in Europe during the 1970s. Thinking back, Blanco laughs and calls this his “black period” because of the depressing and dramatic nature of his work that focused on political ideologies and existentialist absurdity.

These early works were dark-colored and made of harsh materials. He says they had a horror-movie quality that would scare him if he came across one in the middle of the night while stumbling back to the bathroom.

In the late 1980s, something changed. His style did a complete 180. He started using vibrant color palettes and playful geometric designs with the intent of making his viewers smile rather than incite a complicated game of mental gymnastics.

Why? Blanco says he’s no psychologist, but he thinks there were several ingredients that make up the abstract “soup” he’s been cooking ever since.

One pivotal moment was when he met his wife, Elena, who is now in charge of his marketing, promotion, photos, travels, etc.

“The truth is, she is my boss,” Blanco says.

Later, he had his daughter, who helped Blanco see the world as a wide-eyed young person.

Becoming a dad complemented what became two decades of his career spent as the art director for the Museo de los Niños de Caracas, an art, science and technology museum for children.

His theory is, because he had a child and was working at a children’s museum, he was heavily influenced by the playful nature of youth, who tend to gravitate to the colorful and simple-formed.

In 1992, Blanco had his first exhibition in his new style. By 1996, his first public art piece was unveiled in Tokyo.

He was hooked.

Ever since, Blanco’s main goal has been to reach hundreds of thousands of people through public art pieces. He has 24 public sculptures across the U.S. and the world.

“Art is communication,” he says. “And with public art, you can communicate to many people for almost forever.”

That timeless element is the true challenge, however. Blanco says public art takes significantly more detail-oriented planning and time because of added uncontrollable elements such as wind, rain, snow, erosion and vandalism that can deteriorate a piece over time.

But he wouldn’t have it any other way. He thrives on the challenge, which is evident in his most recent accomplishment.

“Bravo” is a public art piece created for a competition for the upcoming roundabout between Orange Avenue and Ringling Boulevard. Amongst 170 entries, Blanco’s was chosen to greet drivers, walkers and bikers all day, every day starting this July.

The idea for the piece came from reflecting on Sarasota’s arts scene.

“My inspiration was the cultural energy of this city,” Blanco says. “We have a ballet, an opera, an orchestra … For the scale of this city, there’s a lot.”

The abstract sculpture has three columns representing the pillars of the local cultural scene, which Blanco believes are music, performing arts and visual arts.

Just like his other public pieces, Blanco knows many people will love it, while many others won’t. But he doesn’t mind. He doesn’t try to appeal to mass audiences.

“You have to do what you feel,” he says.

Blanco loves creating abstract art because of the dramatically different interpretations that people derive from his work.

For example, he used a royal blue color to finish the small-scale sculpture “Peace and Me” on display with 12 other works in his solo show at Alfstad& Contemporary. Many people tell him they think it represents peace or other morals, but he says he painted it blue because he likes blue.

“Frequently people’s interpretations are better than mine,” he says with a playful grin.

Blanco admits to obsessing over perfection, and he finds great power in precisely planned simplicity. But he knows he’ll never be perfect.

“Every piece has a mistake, but it’s a secret — you can only see it with a microscope!”

He takes refuge, however, in his affinity for neat, smooth shapes and surfaces. He doesn’t cut corners. He doesn’t believe in glue or welding, for example, because he thinks they’re too easy and appear sloppy on the finished product.

Instead, he uses bolts, screws and other hardware to assemble his pieces, both by hand and by machine. He compares his assembly method versus welding to home cooking versus warming up a microwaveable meal — he says the added effort creates a better result.

Just as he obsessed over building Lego structures as a kid, Blanco loves designing pieces and figuring out the best way to execute them.

But what’s in it for him?

“It’s a gift to me when people see my pieces and smile,” he says.

Correction: In the print edition of this story that first ran on Wednesday, May 2, the location of Jorge Blanco's hometown was incorrect.