- May 17, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Richard Albero stares at his home office computer screen with his arms crossed, leaning back in a black desk chair.

A video is playing on the YES Network, the television broadcasting partner of the New York Yankees. It’s about Albero, and a long walk he took three years ago, when he was 65. Albero watches the video silently. His desk is covered with photos of his three kids, a crucifix and an outdated Yankees magazine. To his left, a bronzed pair of sneakers hangs on the wall. Behind him is a cross-stitched message that reads, “kindness costs nothing.” The rest of the office wall space is dedicated to the Yankees in one form or another — player statues, pictures, trading cards.

The items in Albero’s Lakewood Ranch office paint almost as clear a picture of his accomplishment as the video. On March 2, 2015, Albero, a retired teacher, stepped on home plate at Tropicana Field (home of the Tampa Bay Rays). Eighty-six days and 1,200 miles later, he strode up to home plate at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx.

All of this in the name of raising money for the Wounded Warrior Project.

He walked through Ocala, where a woman passed him in a pickup truck, made a U-turn and stopped in front of him, hopping out and aiming a shotgun at his head for taking a picture of her property. (“It was pretty,” Albero said.) He walked through Jacksonville, where a man with a hidden blade up his sleeve escorted Albero through a run-down part of town, telling him he’d better hurry or there was a chance he’d “get his a** capped.” He walked through endless fields in North Carolina, where weeds came up to his chest and mosquitoes feasted on his flesh.

He walked every day until he reached the Bronx. He’d stop at night and have one of eight “support drivers” take him to a hotel to sleep. But so exact was Albero about walking the entire distance, without cheating a foot, he’d tie bright kerchiefs around trees so he’d know where he left off.

The closest he came to serious injury — or worse — was in a one-way tunnel in Virginia. He was on the phone with Nick Verrastro, a friend of six decades who had volunteered to be one of his support drivers. The tunnel had a curve at the end, and it was daytime, so Albero couldn’t tell if a car was coming. It was so narrow, he had to walk through it sideways, his lower body rubbing against a railing. As he was approaching the curve, he heard the sound of tires rolling across pavement.

Albero said to Verrastro, “Nick, I’m going to die,” and his friend believed him at the time. As the car neared him, he leapt over the railing, his feet landing on the street on the other side. Somehow, the driver missed him, and Albero walked away unscathed.

“Something was guiding me, whatever you want to believe in,” Albero says. “I don’t know if I’ll ever learn about it in this life.”

The walk forced Albero to rotate 12 pairs of shoes, three of which he wore through completely. He’d never wear the same pair on consecutive treks, and to relieve pain he’d soak his feet at night in Epsom salt in his hotel room. Before the adventure began, he watched YouTube videos demonstrating foot massage techniques. These tutorials came in handy. He got a few blisters, but nothing serious.

Incredibly, the trek had no effect on other aspects of his fitness. He started the walk at 187 pounds and finished it at 187 pounds.

He made three T-shirts for the occasion, neon green ones printed with the words “Walking Tampa to the Bronx.” He wore them every day. He’s wearing one in his office as he watches the video, except now the “ing” in “Walking” has been crossed out with red tape and replaced by “ed.” Walked.

He carried with him a phone charger and a pair of headphones, used in the mornings to listen to Van Morrison or other classic rock artists. In the afternoons, he’d chat with radio personalities along the coast in the hopes of bringing in more donations. Occasionally, he would record audio clips on his phone, documenting how he was feeling. That’s more or less how the journey went down. It was a bare bones operation.

When his journey came to an end, Albero raised $56,000 for the Wounded Warrior Project, including a $25,000 contribution from the Yankees. Along the way, he stopped to visit the charity’s Washington, D.C., office to share with them his mission. He met a veteran named Dave, who told him he represented the bottom figure in the Wounded Warrior logo: the one of a figure carrying his brother in arms. That made Albero proud.

This was more than just an item on a bucket list. There was a purpose behind it, and to Albero the purpose was everything.

No one compares to Babe Ruth.

That’s Albero’s viewpoint anyway. Of all his Yankees gear, items involving “The Bambino” outweigh everything else. Albero has newspapers from the day Ruth died. He has approximately 50 T-shirts related to “The Sultan of Swat” and a cookie jar on his kitchen island in the shape of Ruth. “He has the face of an angel,” he says of Ruth.

He also loves the legend’s penchant for hot dogs and beer, and the way he treated the kids who lionized him, never acting “above” them, Albero says.

Albero loves other Yankees players, of course (Mickey Mantle), and dislikes a few, too (Reggie Jackson). His passion for the team extended to his nephew, Gary Albero, who worked as an insurance broker in New Jersey and was almost as big of a Yankees fan as his uncle. The pair often went to games together, and when they did, they always stopped by Stan’s, a popular bar in the Bronx to have a beer.

Those were special times, Albero says. The pair was so close Albero made Gary the godfather of his son, Dante. Albero remembers Gary used to lift Dante onto his shoulders every time he’d visit; Dante couldn’t get enough of it.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Albero, a New Jersey native, was working as a math teacher at Briarcliff High in Westchester County, New York. He remembers he walked through the library and noticed all the televisions tuned into the same coverage: multiple plane crashes, crumbling buildings, and so many deaths.

In that moment, as he stood there with his eyes fixed on what used to be the World Trade Center, Albero was overcome with a sensation he’d never felt before, or since.

“I got this feeling in my stomach,” he says, “and I just knew. I knew Gary was gone.”

Gary didn’t normally go to the World Trade Center for work. But on that day, as Albero would later discover, Gary had a meeting on one of the center’s top floors.

He didn’t make it out.

He was 39, survived by his wife, Aracelis and his 4-year-old son, Michael.

When Albero first conceived of his long walk, back in November 2014, he saw it as an adventure, a bucket-list item that he wanted to do just to prove he could do it.

But then, in service to this mantra, “kindness costs nothing,” Albero, a former Navy officer, decided to turn his walk into a fundraiser for the Wounded Warrior Project, a cause that made perfect sense to his friends and family. When he dedicated it to his late nephew, however, his inner circle was caught by surprise.

“I didn’t realize how deeply it affected him,” Verrastro says. “People our age don’t like to talk about stuff like that. I think the walk was an outgrowth of having to deal with unspeakable grief. It was a moving thing to see, and pretty remarkable.”

Speaking now, Albero is decidedly mellow about the experience, downplaying the bits about “inner growth.” But the audio clips he recorded along his pilgrimage, which had remained private until he shared them last summer with the Del Webb Lakewood Ranch American Veterans and Military Supporters Group, hint at the depth of his catharsis.

In one of the clips, dated “Day 32,” Albero talks about how happy he is to be walking on a sidewalk. “(I’ve) had a couple weak moments,” he speaks into the recorder. “But I’m reaching down for my soul. It’s still there.” The entire thing lasts 59 seconds.

And then there’s this one — an undated clip that lasts all of 16 seconds.

“Gary, I hope you’re up there watching me, man,” Albero says. He sniffles. “I know I got a ways to go, but I’ll be up in New York on Memorial (Day). Keep me safe. I love you.” The clip ends with the sound of a whizzing car.

Albero says he doesn’t feel different now than he did before he walked. He’s not a better person, nor a changed person. Verrastro agrees, even though he adds that his friend is more “sociable” now and more willing to talk about things going on in his life.

Personal transformation was never Albero’s goal. Now he just wants people to hear his story and know they can unlock the good in themselves, too. He says he didn’t realize it at the time, but that was probably his goal all along.

He is writing a book about his experience, titled “Not Just a Walk in the Park.” He expects it to be published sometime next year. Verrastro says he sees it as another entry in Albero’s crazy life. Albero sees it as a prelude to his next adventure. The 68-year-old is feeling the itch to do something big again. Maybe another walk. Maybe something else. However it plays out, it’ll be for a purpose, just like the last one.

He can’t fathom doing it any other way.

It probably won’t end the same way the first walk did, with Albero wearing those now-bronzed shoes, stomping down on home plate at Yankee Stadium, the place where he and Gary spent so many afternoons together.

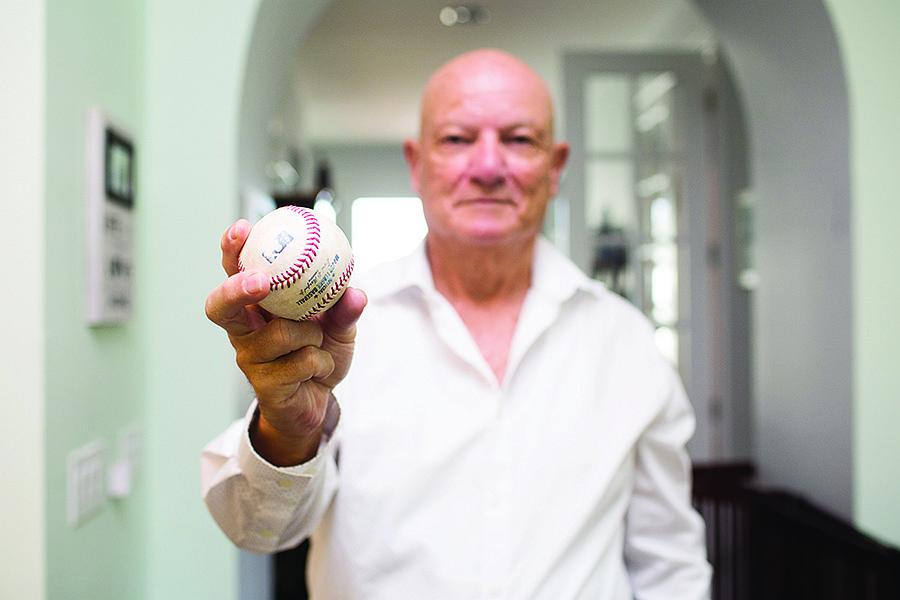

Albero threw out the first pitch at that game, surrounded by his kids. It was a perfect strike. Not even Babe Ruth — people forget he was also a masterful pitcher — could have done better.

After the game, Albero went to the only place that felt appropriate, Stan’s.

He stood on the bar, beer in hand, and toasted to Gary’s memory.

The bar toasted back.