- November 15, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

He shall make the final decision.

In James Palmer's world of labor relations arbitration, words mean everything. As he puts it, when a contract is drawn, those writing the words had a reason for doing so, or they would have selected different words.

"There is special significance to the word 'shall,'" said Palmer, who lives in Country Club East. "It doesn't mean maybe. It means it will happen."

When either management or employees twist shalls into maybes, such conflict can eventually be decided by an arbitrator, such as Palmer, who is the principal for ADR Neutrals, LLC, and the principal consultant for the Center for Creative Employee Relations, LLC.

"You have to know a little about word usage," Palmer said of understanding the terms of any contract. "You have to know about the construction of sentences. Then you apply a set of factors to the language of an agreement. You try to ask, 'Why did you do what you did?' Then you can only make a decision on the facts as presented. How impacted were the employee's actions by the language of the agreements?"

It all might seem simple in nature, but it isn't. Palmer's ability to understand labor relations contracts has been crafted over a lifetime of human resources and labor relations work, and it has set him apart in his industry.

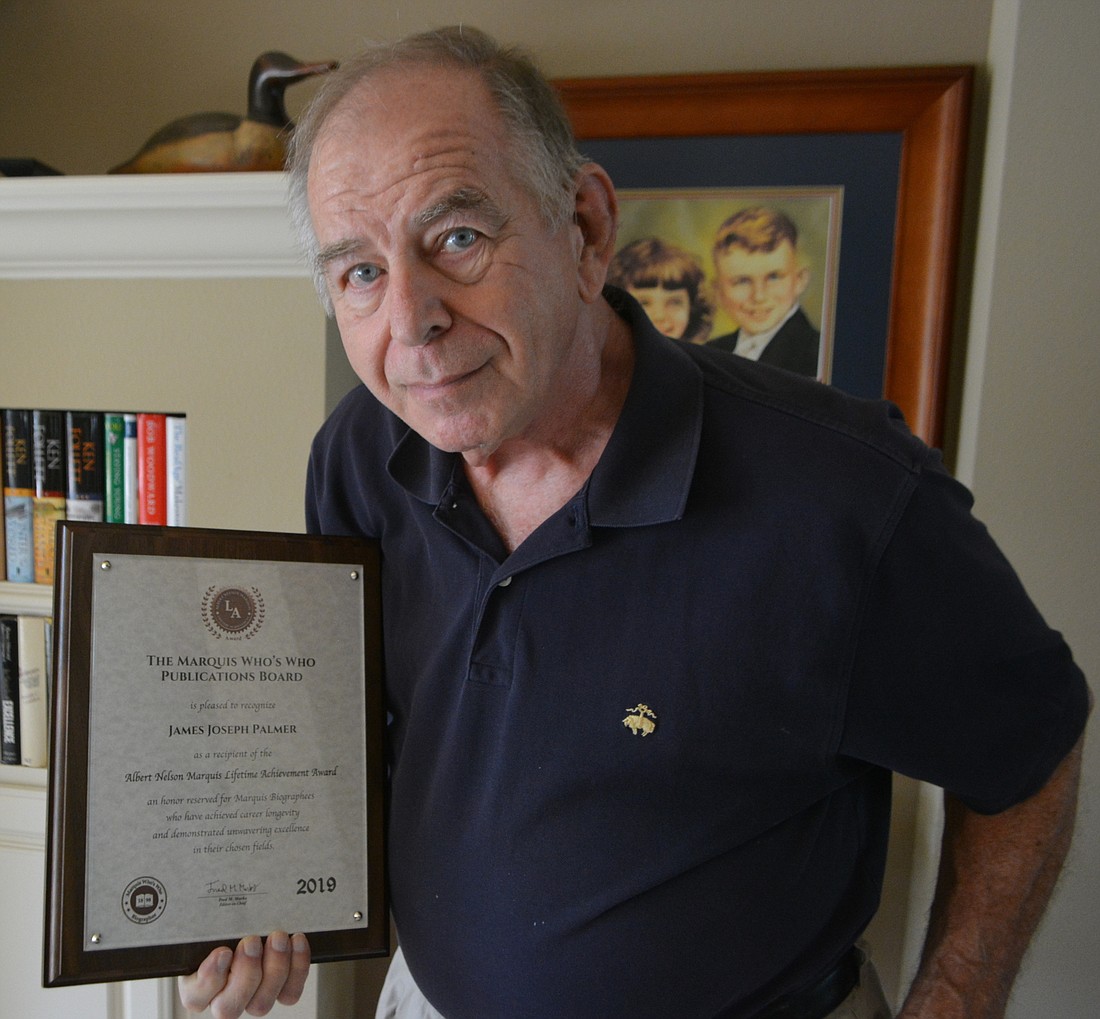

In 2016, Palmer's firm, ADR Neutrals, was selected as the "Best International Labour-Management Relations Firm," by Acquisition International Magazine. In July, Palmer was awarded the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award by Marquis Who's Who.

One of his former adversaries, Willie Thorpe, was asked if he thought Palmer would be pulling down such honors as an arbitrator.

"Heck yeah," said Thorpe, who is still an official for the International Union of Electrical, Technical, Salaried, Machine and Furniture Workers in Dayton, Ohio, years after facing off against Palmer. "He knows the language, and he stays in the boundaries of what the contract says. If you want someone who has been there, who knows the intent of a contract, you are going to call him."

When it comes to having been there, Thorpe knows Palmer has the experience. It was the beginning of the 1980s when Palmer was dispatched to Dayton, Ohio by Chrysler, which was in the process of either selling, closing or making competitive their parts plants. In many cases, those parts could be made cheaper overseas.

Even though he was paid by Chrysler, Palmer earned the respect of Thorpe, who represented the union. It might also be noted that Thorpe had the reputation of being a tough guy, one who actually had wrestled a bear ... a real bear.

But even today, it was obvious why the two got along. Sitting at his Country Club East home, Palmer was the picture of an executive ... well-spoken, organized, intelligent, calm. Yet, as he told stories of his labor relations negotiations he would sprinkle in a few profanities, showing he could be just one of the guys at an automotive plant.

And, of course, there was his straightforward and honest approach, which he learned growing up in the schools of Detroit in which he was taught by nuns.

"When I first met Jim, I liked him," Thorpe said. "When he said something, you could count on it because it was set in concrete. He was dependable and honest, and his word meant something. You knew where he was coming from."

Palmer didn't go into Dayton, where the plant had been in operation since the 1930s, with the intention of shutting it down. He knew he had Thorpe's respect, and he decided to introduce a new concept of "shared destiny."

"We had to have a decent relationship with the people in those plants," Palmer said. "And the union guys were very trusting of me. They believed my job, first and foremost, was not to close plants. So we introduced a system where you would share with employees a portion of the profits."

"For example, typically housekeeping at a plant was picking up screws and washers in a goodly number that had ended up on the floor. We started seeing employees walking along with a magnet on a string. They were recapturing all that was lost. It caused people to think about those screws and washers on the floor."

Palmer was able to negotiate a wage freeze, plus the gain sharing, and they signed an unheard of 12 1/2-year labor agreement. The plant still is in operation, although now owned by the German company, MAHLE GmbH.

"We got people working together ... it was a mind changer," Palmer said of his work in Dayton. "I used to call it, 'What's in it for me?'"

His career with Chrysler started in 1968 and he retired from Chrysler in 2001. At times, it wasn't so easy.

"'I'm not sure I could count the number of people I've discharged," he said. "I remember one day (at a Detroit plant) I went through the ritual. In those days, they still allowed smoking in offices. I kept an ash tray on the corner of my desk. This employee says to me, 'Are we through?' He grabs the ash tray and smashes it into my head. If he used the corner of it, he would have killed me."

It was in 1970 when Palmer was switched by Chrysler into labor relations amidst tragic circumstances.

Palmer was assigned to Chrysler's Eldon Avenue Gear and Axle Plant, where an employee on the assembly line, James Johnson Jr., brought an M-1 carbine to the plant and shot three people to death, including two foremen. Reports said Johnson snapped because of terrible conditions at the plant which had led to the deaths of two of his co-workers less than a year before Johnson's rampage.

"The union leadership was relatively aggressive at the time," Palmer said. "The relationship wth labor relations frequently was strained. After Johnson killed those three people, somebody woke up and said maybe we should change the way we conduct our relationships. 'Let's make Jim a labor guy.' Maybe I wasn't as crusty as the other guys, but that was the beginning of what became a labor relations career."

During that career, Thorpe started calling him Doctor Palmer. "I could make complex things relatively simple," Palmer said.

Now he works not-so-simple labor relations cases as an arbitrator along the Interstate 75 corridor from Michigan to Florida. He knows in each of those cases, someone is going away unhappy.

"Somebody has got to make a decision," Palmer said. "The main thing is you need to teach so they don't make the same mistake. It's the only way you improve."