- December 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Editor’s note: This is the first of two installments examining the affordable housing situation in Sarasota and Manatee counties. This week, we present the problem. Next week, we examine solutions.

After taking some time to assess her financial situation, Haley Hines arrived at a conclusion: Her best option for saving money while living in Sarasota was to move into her van.

Rather than getting an apartment near her job at a Lakewood Ranch fitness studio, the 20-year-old spent six months dedicating her income to food, transportation, insurance and student loan payments. The one-bedroom apartments she saw cost more than $1,300 a month. Housing, she decided, was a luxury.

“I’m a person; I have bills,” Hines said. “To be able to build up financially, to be able to save money, you have to drastically cut costs somewhere, and rent was just what made the most sense. It was what was doable because I need a car. I need food. A house is optional.”

A shortage of affordable housing has become a pressing issue in Sarasota — for residents like Hines searching for a place to live, for businesses working to hire and retain employees, and for officials searching for solutions to a complex challenge.

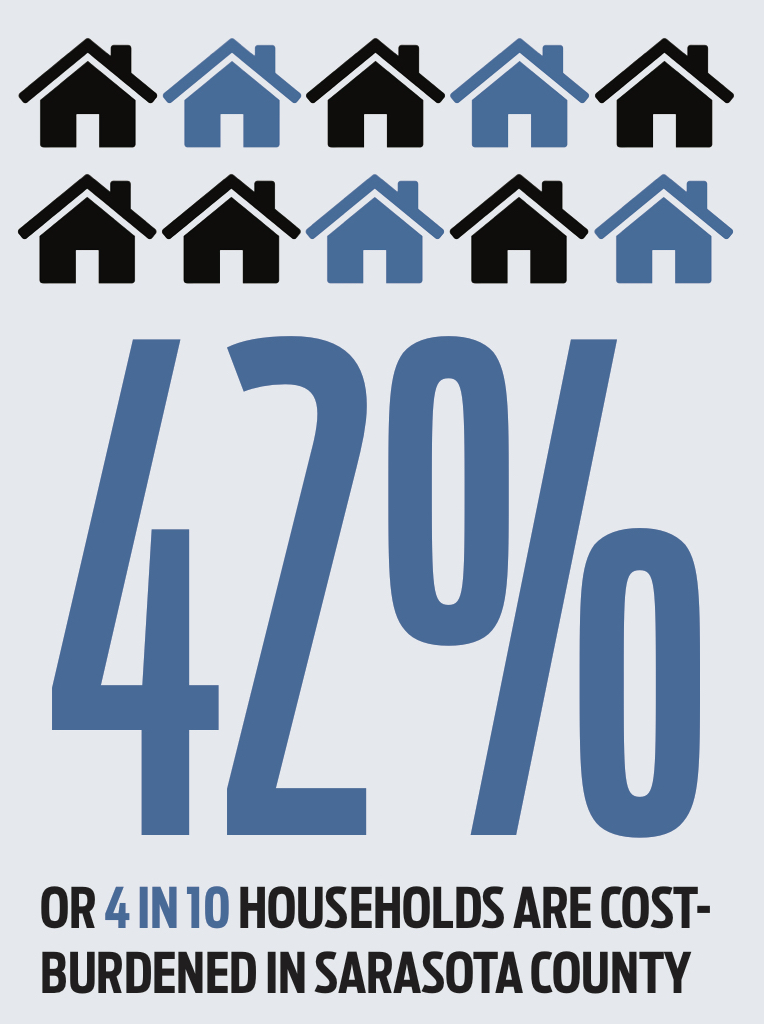

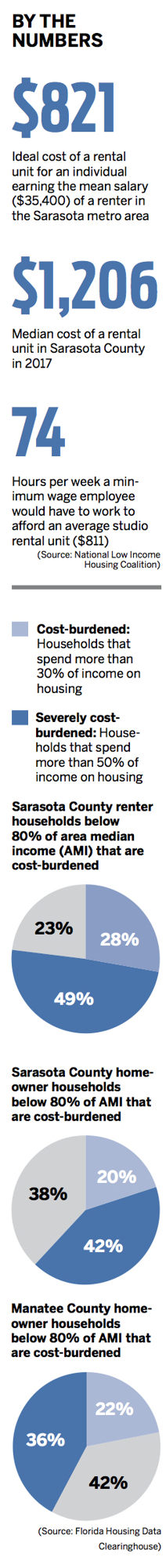

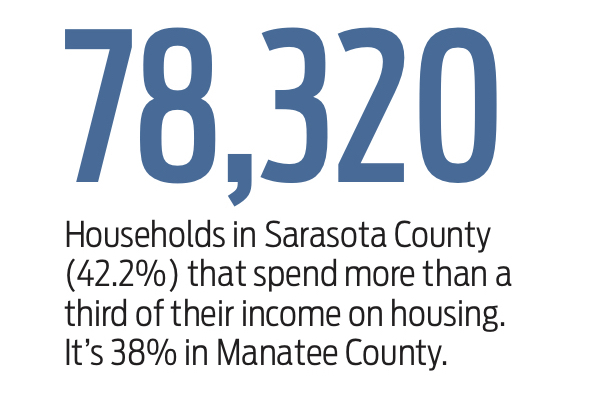

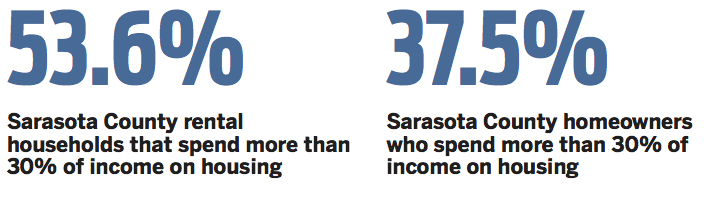

According to a 2016 estimate, the most recent data available from the Florida Housing Data Clearinghouse, 42.2% of all Sarasota County households are dealing with an unaffordable living situation.

In the past year, elected leaders in Sarasota County and the city of Sarasota have heard presentations from advisory committees and external experts on housing. They’ve passed new laws designed to encourage the production of more affordable units.

Experts say the problem is affecting a broad spectrum of Sarasota residents, from younger individuals early in their careers to seniors living on fixed income. It influences other issues the community is facing, from homelessness to traffic congestion and beyond.

During these conversations, there’s little disputing the notion affordable housing is a legitimate problem — a crisis, some say.

“It’s severe enough to the point where a lot of our waiting lists are closed because there’s so many people on them that we can’t — it’s almost pointless to keep adding people,” said William Russell, president and CEO of the Sarasota Housing Authority.

Even in the wealthiest pockets of Sarasota, the affordable housing shortage has noticeable effects.

Michael Garey, owner of The Lazy Lobster on Longboat Key, said housing is forcing restaurant and retail store owners on Sarasota’s barrier islands to constantly search for employees. It’s not just that service workers can’t find a place to live on Longboat or Lido Key; they’re struggling to find a place they can afford with an acceptable commute to work.

That’s one of the reasons employers, officials and residents say a lack of affordable housing affects the quality of living for more well-off Sarasotans. It’s a common refrain applied to various industries including hospitality, the arts, health care and home maintenance.

“The simple fact is that the lifestyle that we sell to come and live here cannot be supported without the needed workforce,” Garey said. “They simply just cannot afford to find a place to live here.”

One of Garey’s employees, 34-year-old Michelle Waldron, is in the market for a home in the Sarasota area. She and her boyfriend would be first-time homeowners. Although she works two jobs — one as assistant manager at the Longboat Key restaurant — and she’s part of a two-income household, they’re struggling to find a house in their price range, about $275,000.

As a result, their search has expanded to Parrish, 30 miles from where she and her boyfriend both work. It’s not ideal, she said, but the prospect of a more desirable location feels unattainable.

“It’s ridiculous,” Waldron said. “We have a pretty strong income, and we can’t afford to save money because everything goes toward our living expenses.”

Members of business organizations, including the Greater Sarasota Chamber of Commerce, have listed workforce development as a primary concern, and housing costs are a major driver of their fears. Major regional employers, such as Sarasota Memorial Hospital and the Sarasota and Manatee school districts, have cited housing as an impediment to employee recruitment and retention.

“One of the first things people do is look up, ‘What is it going to cost for me to live there?’ and they realize the housing is relatively unaffordable for someone on, say, a teacher’s salary,” Russell said.

Alex Guardia spends more than an hour daily commuting to and from his job at Braden River Middle School in East Manatee County. His rent is rising at his west Bradenton apartment, which he first leased for about $1,200 a month. The closer to his job he looks, the more expensive his options are.

He’s happy with his job, but the housing situation takes a toll on him sometimes. In addition to the financial challenges, there are physical and mental stressors. When he has work engagements scheduled before and after school, he doesn’t have an opportunity to run home to kill time. He says that it might seem small, but spending 12 hours or more away from his house can be draining.

“It really does tax the body,” Guardia said. “You get home, and you finally get to decompress, and it’s time for bed.”

Planners and other officials point out that the effects of longer commutes aren’t just limited to workers and their employers. Traffic was the No. 2 issue listed in Sarasota County’s 2019 resident survey. Sarasota City Commissioner Hagen Brody said residents might not immediately think of a lack of affordable housing as a primary driver of that traffic, but it’s certainly making matters worse.

In discussing why he thinks Sarasota needs to prioritize the facilitation of more affordable housing, Brody encouraged the public to consider the broader implications of the issue.

“If we don’t do that, we’re going to see increases in traffic congestion from people traveling in from outside of the community day in and day out,” Brody said. “We’re going to lose a lot of opportunities with bright and creative and driven young people that want to start a business here or a restaurant or a coffee shop. Those are the things that make a community.”

Rising housing costs are affecting communities across the country, but there are some factors amplifying the severity of the issue in Sarasota.

Steve Cover, the city of Sarasota’s planning director, said one obvious reason costs are going up is because there’s a market for higher-end housing and money to be made building it. That’s not surprising for a coastal community that has historically emphasized serving the affluent.

“Whenever you have something like this where a city is in such demand, the new development is going to lean toward being more expensive and more luxurious,” Cover said.

Jane Grogg, Sarasota County’s manager of neighborhood services and long-range planning, said seasonality also affects the housing inventory in the area. About 14% of homes in Sarasota County are for seasonal use, compared to 10% statewide and 4% in the U.S.

Local officials also note they’ve dealt with challenges associated with obtaining funding for projects. In particular, since the early ‘90s, the Florida Legislature has reallocated more than $2 billion in money away from an affordable housing trust fund.

But some say policies in Sarasota encouraged the production of more expensive units and made it difficult to build modestly priced homes. That includes Daniel Herriges, a Sarasota resident and employee of the civic planning nonprofit Strong Towns. Herriges is a proponent of a strain of planning philosophy that suggests a prohibition on higher-density multifamily housing serves as an impediment to the creation of affordable housing.

An emphasis on single-family housing, written into the city and county’s zoning code, limits the number of housing units that can be built while making it easiest to build the most expensive type of housing. The areas where multifamily housing is allowed are mostly in the urban core, where land is most expensive. Even there, a lack of affordability mandates and a maximum density of 50 units per acre prior to 2013 led to an emphasis on larger luxury condos.

A shortage of affordable housing is the natural product of those regulations, Herriges said. Those involved in the housing conversation discuss the “missing middle,” a shortage of smaller units, such as townhomes or apartments, priced for those on a moderate income. Herriges said those sorts of buildings were woven into neighborhoods such as Laurel Park prior to 1950, but began to get legislated out of existence after that.

“Downzoning in the 20th century made it so the ways that we used to build neighborhoods that had a mix of little cottages, bigger homes, triplexes, small apartment buildings that used to be completely normal — we made it illegal,” Herriges said. “Not just in Sarasota but in most American cities.”

Until recently, production of new units had slowed after the 2007 housing crash. According to census estimates, 6,243 new housing units were built in the county between 2010 and 2017 — 2.6% of the 234,414 total units available in Sarasota. By comparison, an average of about 45,500 of those units were built each decade between 1970 and 2010.

“It’s never been a lack of demand that has prevented multifamily housing in Sarasota.” — Donald Paxton

Although the number of new housing structures is trending up toward prerecession rates, the lull after the crash exacerbated an existing affordability challenge. Russell said the production slowdown combined with the foreclosure crisis created a much higher demand for rental units.

Until recently, he said, that demand wasn’t being recognized.

“We had such an acutely low supply of rental housing of any kind,” Russell said. “We didn’t build apartments here for, I think, a good 20 years.”

Affordable housing developer Donald Paxton thinks that in the past, Sarasota officials have erred in limiting the areas where multifamily housing is allowed. He hopes that’s changing.

“Over the last five years, you’ve seen a huge influx of multifamily,” Paxton said. “That’s not just because there’s a demand. It’s never been a lack of demand that has prevented multifamily housing in Sarasota.”

Other builders cited impact fees — imposed by local governments to account for the impact that development has on public resources, such as roads and schools — as an impediment to affordability. City and county officials say they’re limited in their ability to restrict impact fees for new construction, but developer Pat Neal of Neal Communities estimated regulatory-related expenses can cost around $40,000 per home.

Beyond the work the Sarasota Housing Authority has done to build public housing and distribute housing choice vouchers, many efforts to create more affordable housing in Sarasota have not produced the desired results. In 2004, the city created a Downtown Residential Overlay District that authorized higher-density projects in exchange for contributions to an affordable housing fund. Four projects were approved, but only one has contributed money toward it so far, a payment of $252,500 from a developer the city cannot definitively identify today.

In 2014, the city waived an affordable housing payment for The DeSota apartments after the developer reduced the size of some units below 1,250 square feet. Today, available units at The DeSota start at $1,854 per month for one bedroom and $2,901 per month for two bedrooms.

Sarasota County officials also weakened affordability provisions as the region emerged from the 2007 recession, including eliminating an obligation to build as many as 437 affordable homes in Benderson Development’s University Town Center project.

When the commission moved in 2015 to lower the affordable housing obligations of a 600-home development east of Interstate 75, board members defended the decision as a compromise reflecting the needs of developers. Paul Caragiulo, then a county commissioner, suggested affordable housing initiatives should focus on more urban areas and multifamily projects rather than new sprawling communities.

“You’re not going to tackle affordable housing with single-family units,” Caragiulo said.

Dan Lobeck, leader of the group Control Growth Now, was critical of local leaders’ handling of previous affordable housing mandates.

“The problem has been a refusal on the part of the County Commission to be serious about affordable housing,” Lobeck said.

The Blueprint for Workforce Housing, a report the Florida Housing Coalition produced for Sarasota County and the city of Sarasota, said officials had a good knowledge of affordable housing strategies but had generally failed to effectively implement them. The report identified political will as a crucial ingredient for avoiding the failures of the past.

“The key to success will be local, elected leadership committed to ensuring that workforce housing is provided in Sarasota County and the city of Sarasota,” the report states.

Despite the factors contributing to an affordable housing shortage today, Sarasota leaders are optimistic progress is being made. Still, questions remain about whether the changes under consideration are sufficient, as well as concerns about obstacles that could complicate the pursuit of more affordable housing.

David Conway, Pam Eubanks, Jay Heater, Brynn Mechem, Liz Ramos and Sten Spinella contributed reporting.