- May 15, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

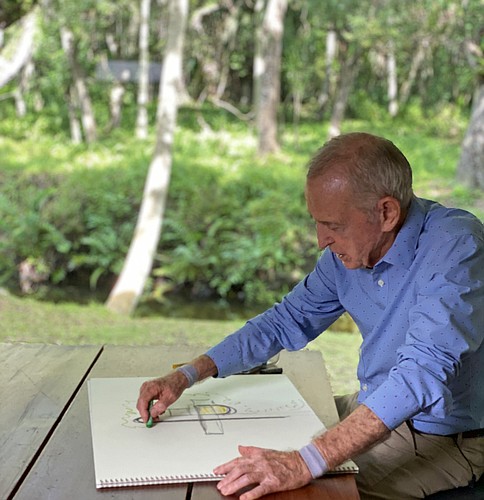

Architects work with a variety of elements. Time is one of them—and Carl Abbott knows it. He was perhaps the youngest Sarasota School architect; he’s now the movement’s de facto elder statesman. St Thomas More Catholic Church, The Putterman House, Pine View, the Summerhouse, and the Dolphin House are just some of Abbott’s iconic structures in our area’s volatile landscape. That’s not counting his demolished legacy—but he accepts that loss philosophically. To create in the material world, that’s the price you have to pay. Abbott’s acutely aware of each building’s connection (and vulnerability) to the constantly changing world around it. He’s equally conscious of the currents of architectural history—and what it takes to pass that history on from one generation to the next. That’s why Abbott is just as passionate about teaching architecture as creating it. And why he’s sharing his insights at SarasotaMOD Weekend 2020. Abbott’s been doing this kind of thing for years for students of all descriptions. I’m one of them. For this architecture school dropout, each talk is always a refresher course. Here are some of Abbott’s latest lessons.

What’s the heart of your architectural process?

The land, of course. It’s right there in the title of my book—“Informed by the Land.”

That’s what I figured. But now that you said it, I can quote you.

Well, for the record, I use the same process for all of my projects, big or small. Whether I’m designing a home, a church, a school, or whatever—the land is always my starting point.

What does that look like in practice?

I begin each project with a direct, first-hand experience of the land. I’ll go the site and meet the clients. Then I’ll study the physical environment. What are the potential views? How would the building relate to the land? After that, I’ll investigate what the clients want, how they would relate to the land, their patterns of life, and what their daily experience would be in a future building.

The last part is the work of the imagination. But you start with the thing itself: the land. You need to see it with your own eyes before you start imagining.

Yes. After studying the reality, I go back to the abstractions of the human realm. I’ll study the land on county maps, Google Earth, aerial photography … and so on. Then, I’ll explore the limits of the building code. How high can we legally go? What would the view look like? I’ll often rent a cherry picker to know precisely.

Some artists make site-specific sculpture. You make site-specific architecture. The land is your canvas.

That’s true. But it’s not a blank canvas. I’m trying to hit a moving target.

How so?

The land changes. Nature is not a static reality. Each site constantly changes over the course of a year or a day. As an architect, you have to consider the different angles of sunlight in winter and summer, how the breezes change—a multitude of different factors.

Time, in other words. You don’t just think about space. You think about space-time. You’re “informed by the land” over weeks and months and years.

I try to be. I think about movements in time and space. This approach informs the way I design buildings. It’s not original by any means. Frank Lloyd Wright knew these principles—his “organic architecture” was all about that. The ancients also knew them—you can see it in traditional Maya and Egyptian architecture.

OK. Just to play Philistine’s advocate … My house is air-conditioned and the pool is heated. It’s sunny in June and cloudy in November. Why should I care?

I’ll tell you. People often think about architecture in utilitarian terms. “Form follows function,” and so forth. What is the building for? What will people do with it? Well, functionally speaking, a building might be a machine for living, or a workplace, a place to sleep, or what have you.

George Carlin called it “a place for your stuff.”

Perfectly valid. But people often overlook one essential function. Architecture also has an experiential dimension. Great architecture connects you to the world. It opens the doors of perception.

Please expand on that.

I’ve taught a series of college courses over the years. After a few classes, I usually ask my students, “Have you noticed what’s blooming outside?” The answer is always no. They didn’t. I’ll repeat the question a few weeks later. The answer is still no.

And these are architecture students! You’d think they’d notice.

You’d think so. What’s growing outside your window?

Trees. Or one tree. A mango, I think.

What does it look like?

Uh. Rough bark. The leaves are kind of … floppy?

Do you know when it bears fruit?

No.

Now you see what I’m talking about.

I didn’t know there’d be a test.

I’m not trying to single you out, Marty. Most of us are blind to daily natural phenomena. Ephemeral delights like shadows, rainbows, trees and flowers just don’t register. Right now, chorisia trees are blossoming in this part of Florida. The flowers look like cherry blossoms! Jacarandas are as vibrant as fireworks. But most of us don’t notice the beautiful, subtle changes in the outside world.

So … you design your buildings to make people notice. Some architects create air-conditioned Thermos bottles. You don’t. You try to connect people to the beautiful, changing reality outside.

That’s my approach—and it’s not the only valid one. Modern architecture comes in many flavors. My buildings look outward. Others look inward—they’re self-referential. Some architects are informed by computer design. Others think in sculptural terms—Eero Saarinen and Victor Lundy, off the top of my head. Frank Gehry’s work is extremely sculptural—and he starts from crumpled up wads of paper.

Ah. Speaking of which, your architecture has sculptural elements. I understand you also create literal sculptures. There’s an exhibition at Art Center Sarasota, right?

Right. But there’s a line between my architecture and my sculpture. My thinking is different. My sculpture is portable—you can exhibit it anywhere. Move a piece from Point A to Point B and it still works. My buildings wouldn’t work if you moved them to different sites. If such a thing was possible.

As an architect, which buildings give you the most pride?

That question comes up frequently. My answer is: The great buildings I’ve helped to save—which are not all modern. SAF saved both the Paul Rudolph canopy and the exterior of the original Sarasota High School building. That’s something we’re very proud of. We also fought to preserve Rudolph’s Riverview campus—but that’s one battle we didn’t win.

The fight for architectural preservation is never-ending. In Florida, it often seems like a lost cause …

It isn’t, not even in Florida. But we have to change public awareness to win. What does architectural preservation actually mean? There’s often a fundamental misunderstanding—on both sides. It’s not a question of preserving the dead past in amber. It’s not a fight against change. That’s never going to work.

What would work?

Good question—and it’s been on my mind. Broadly speaking, architects should design for change. We’d think in terms of decades—our designs would reflect that. To make that happen, our work should fall into three categories. That’s a concept I’ve been developing …

Please elaborate.

Some iconic, historic buildings would be altered as little as possible. Other structures would constantly change—by design. They’d function as shells for moveable interior elements. Other buildings could be completely temporary—designed for specific uses, then dismantled. I think it’s a workable model—and it’s reality-based. Buildings and use change over time—and that’s never going to change. People adapt them to their own wants and needs. The urban environment around our structures is also in flux—along with the natural landscape. With climate change, that could be catastrophic.

And now we’re back in the time stream.

Yes—and if architects try to fight it, we’ll sink. Preserving our architectural heritage is important. But preserving the thinking behind our great buildings is even more vital. That’s why I’m so committed to teaching. I owe a debt to my teachers and mentors—Paul Rudolph, I.M. Pei, Buckminster Fuller and many others. That’s a key reason I speak at events like SarasotaMOD Weekend, aside from the personal enjoyment and the honor. Having three architectural events revolving around my work is a great, great honor.

That reminds me of a martial arts tradition. A student learns from the teachers of the last generation. That creates a responsibility to teach the next generation. You have to pass your knowledge on.

I believe in that very strongly. And of course you also learn by teaching.

What’s your definition of a great building?

A great building is never dead. A great building has life. They’re almost like children—and I have many beloved children of my own. I know my work will change over the years. But it’s alive. For me, that’s enough.