- April 4, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

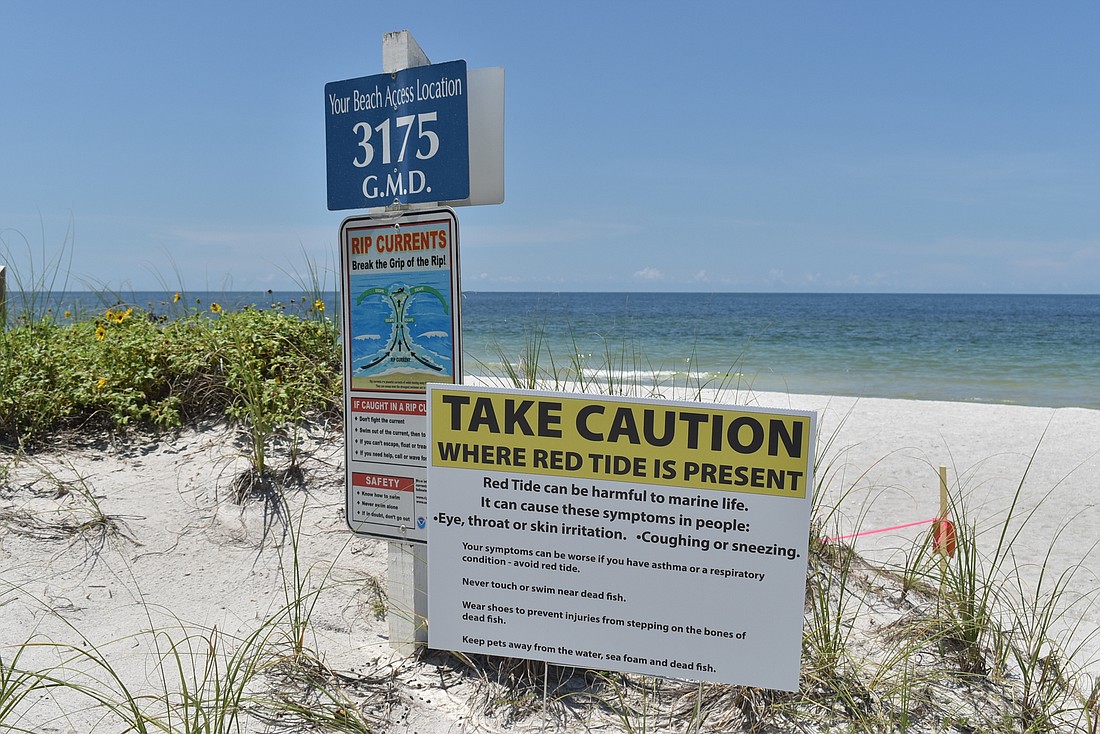

At this point in the 2021 red tide bloom, most Longboat Key residents probably know the basics: it’s an algae bloom, it kills fish and it causes respiratory problems in people. But the days are going by, the stink is hanging around and more fish are washing up on the beaches. Despite the gloomy outlook, there are a few facts we might not have learned if not for red tide. Among them:

Red tide mitigation has included using the byproducts of beer brewing and ozone, but the latest experiments involves spraying clay over the karenia brevis-laden water. Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, in partnership with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission, have 25 projects underway, according to a July 16 article on Mote’s website.

As the current bloom started expanding, Mote scientists along with researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and the University of Central Florida, began deploying clay mitigation. This means that they’re mixing dry clay with seawater to create a slurry that is sprayed over the blooms. As clay sinks, it should take red tide cells with it to the bottom. The karenia brevis will die or be buried on the seafloor.

Longboat Key residents learned in late July that sharks were making a break from the red tide-choked waters they normally swim in and settling in canals. Clearwater Florida Fish and Wildlife Commision research administrator Leanne Flewelling said that some species like sharks and rays avoid the blooms. Unfortunately, they can get stuck there, too.

“Typically, it's not the (dissolved oxygen) issue when we have fish kills and red tides because of the toxins,” Flewelling said. “It doesn't take much toxin to kill the fish ... A lot of species can just try to avoid it. So, we don't usually see mass mortality of sharks or stingrays.”

Some species, like the planktivorous fish on the bottom of the food chain that feed on tiny organisms, can eat it and not be too affected. Flewelling said they’ve seen this in mammal models, too. When a mouse is injected with toxins, it is much more lethal than when they just consume it.

“When they eat it, it's not harmful to them,” Flewelling said. “What kills them is when those toxins are in the water and they’re exposed to it across their gills … which is why planktivorous fish can accumulate enough karenia in their intestines or GI tract to become lethal vectors for dolphins and seabirds.”

Some of the dead fish washing ashore are those that live most of their lives on the bottom of the ocean, like eels and catfish. At night, karenia brevis is more distributed throughout the water column and can be denser at the bottom, Flewelling said.

“Sometimes, you get fish kills of (bottom) species,” Flewelling said. “It’s kind of unusual for people to see all these eels on the beach.”

As a bloom goes on and gets more dense, it starts to effect the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water.

“So when the fish sink to the bottom and they start to decay, when the cells are in enough abundance, they’re also using oxygen and can strip oxygen from the water, and you might get kills from species that you typically see at the bottom,” Flewelling said.

Though blooms have been getting more severe, karenia brevis predates humans. It’s a naturally occurring phenomenon, Flewelling said, and while it can be transported elsewhere, it’s actually unique to the Gulf of Mexico.

“It has shaped the ecosystem,” Flewelling said. “I’ve heard people compare the effect of red tides to wildfires, which serve an ecosystem function, and karenia fills a niche. If it were gone, we don’t know what it would look like, maybe we would have a more toxic species or a different toxic species.”

That’s hard to think about when these exacerbated blooms are occuring, Flewelling said. However, offshore fisheries are still pretty resilient to the blooms.

One aspect of turtle nesting season that becomes a bit more top-of-mind during a red tide bloom is the fact that neither nesting nor hatchling turtles eat a lot close to shore. When hatchlings set off for the big blue world, they have a yolk sac left over from the egg that continues to feed them. Hatchling sea turtles naturally begin swimming as they hit the water and don’t stop until they get to the weed line, which can be a variable distance from shore.

“That’s supposed to be good for three days of swimming, so they have a good chance of getting into waters where they can be normal turtles,” Longboat Key Turtle Watch vice president Cyndi Seamon said. “It’s kind of hopeful. It’s bad out here, but their little brain says, ‘Keep swimming, you have food, keep going.’”

When adult females are nesting, they also don’t eat for a while as they’re migrating. They’ll forage after the eggs are safely in the sand. However, the turtles are still breathing in the air that contains toxins, and Mote has recently had adults come in with red tide.

“Hatchlings have the yolk sac so when they hit the water running, they don’t have to eat anything, and our hope is the red tide is close to shore and they’re past it before they have to consume anything,” Seamon said.