- November 28, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

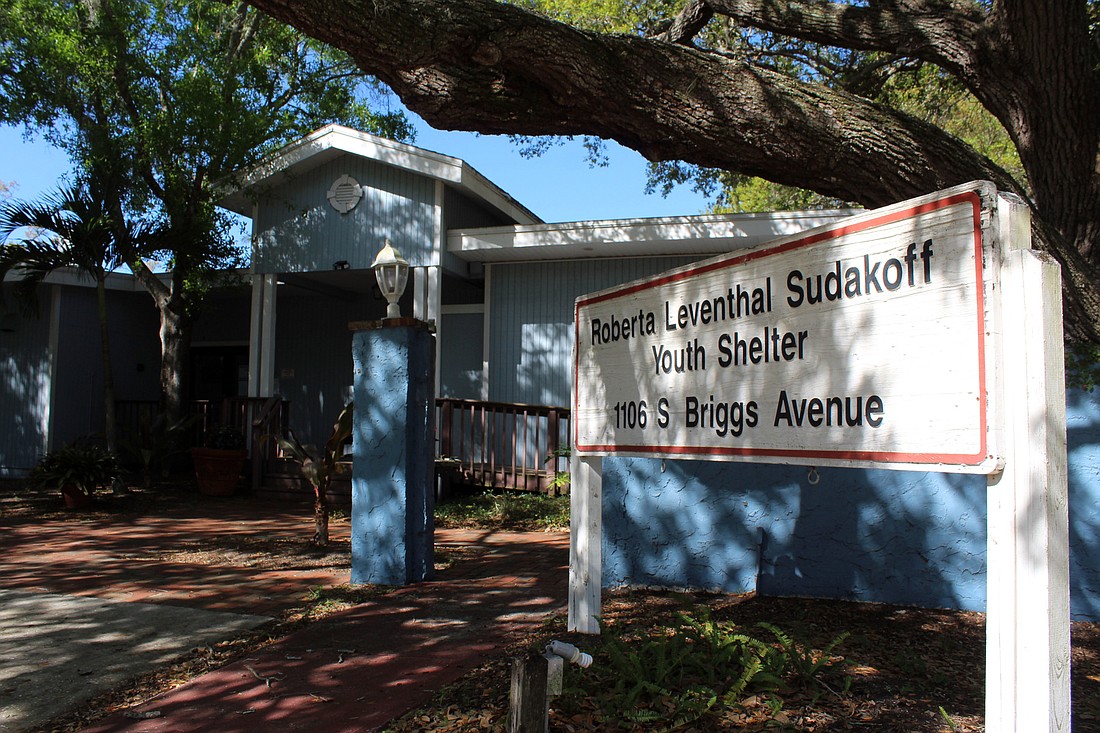

On a breezy Tuesday morning, Aaron Bellamy bounces from room to room in the Roberta Leventhal Sudakoff Youth Shelter.

In one room, he answers phone calls from concerned parents. In another, he coordinates a furniture delivery from the Junior League of Sarasota. As he moves, he asks children how their day is, his eyes crinkling from what’s sure to be a wide smile hidden beneath his mask.

“So now you’ve seen what our day-to-day is like here,” Bellamy said. “It’s hectic.”

Although he’s joking, the frenetic morning is a reflection of the year Safe Children Coalition has had navigating the pandemic.

Brena Slater, the president and CEO, said the organization has had to rethink how it runs many of its programs while facilitating services for an increased number of children.

Although overall cases reported to the state dropped in 2020, the number of children removed from homes in the area SCC serves stayed the same. In March and April 2020, SCC entered 70 children from Sarasota and Manatee counties into its system.

“The number of all these abuse reports dropped, but it wasn’t really happening. There was still abuse,” Slater said. “It wouldn’t be a teacher suspecting there was abuse and reporting it. Unfortunately, it would often be a child at the emergency room that had a severe injury.”

Throughout all of 2020, SCC served about 2,300 foster children, 700 of which were removed from their parents.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that job loss, accumulated stress, school closures and social isolation resulting from COVID-19 has increased the risk for child abuse and neglect.

Because of that increased risk, SCC caseworkers immediately returned to the field to visit high-risk families and children.

One concern for SCC caseworkers is that in using Zoom, people can restrict the camera’s view to certain areas of the home. Caseworkers needed to be in people’s homes to get a full view of a living scenario.

“Our kids have to be seen no matter what,” Slater said. “We didn’t have the luxury of being able to say, ‘We’re closed; we’re going online.’ We had to continue to take care of our children whether they were in our shelter, our group home or their homes.”

Although it’s been difficult adapting to virtual meetings, Slater said, in some ways, it has allowed caseworkers to make a deeper connection with children because they were able to have more contact with them.

“We started calling families more and doing more FaceTime visits,” she said. “We are required to see the children once a month, but case managers began calling multiple times a week, so we found that our number of contacts with families increased dramatically.”

Another positive to come out of COVID-19 is an increased number of licensed foster parents. Licensing has been held online, which removed the barrier of driving to the SCC offices, and more people signed up because they are working from home.

Another issue SCC had to overcome was closed court systems. For about six months, the only court hearings held were for emergencies when a child is removed from a home, which meant foster hearings and delinquency courts were closed.

SCC also saw an increase in children who have mental health needs. Many of those children were placed in the organization’s youth shelter, which put a strain on the capacity of 18 children.

“There’s a lot of days when we have 15 or 16 children in our shelter,” Slater said. “Over the last several months, the need just keeps getting higher and higher.”

SCC leaders hope to expand its shelter services by purchasing a new facility when the lease on its current shelter ends in two years.

The shelter is currently set up with two dorm-style rooms and two single rooms. The trouble with that, Slater said, is when the shelter is servicing more than two children who might be a threat to others or who are on a special safety plan.

“We want every child to feel respect and comfortable when they’re at our shelter,” she said

Director of Philanthropy Jacqueline House said SCC will launch a capital campaign in the coming months to raise money for a land purchase and construction.