- January 7, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

On one wall, there’s a scene of a sacred wedding.

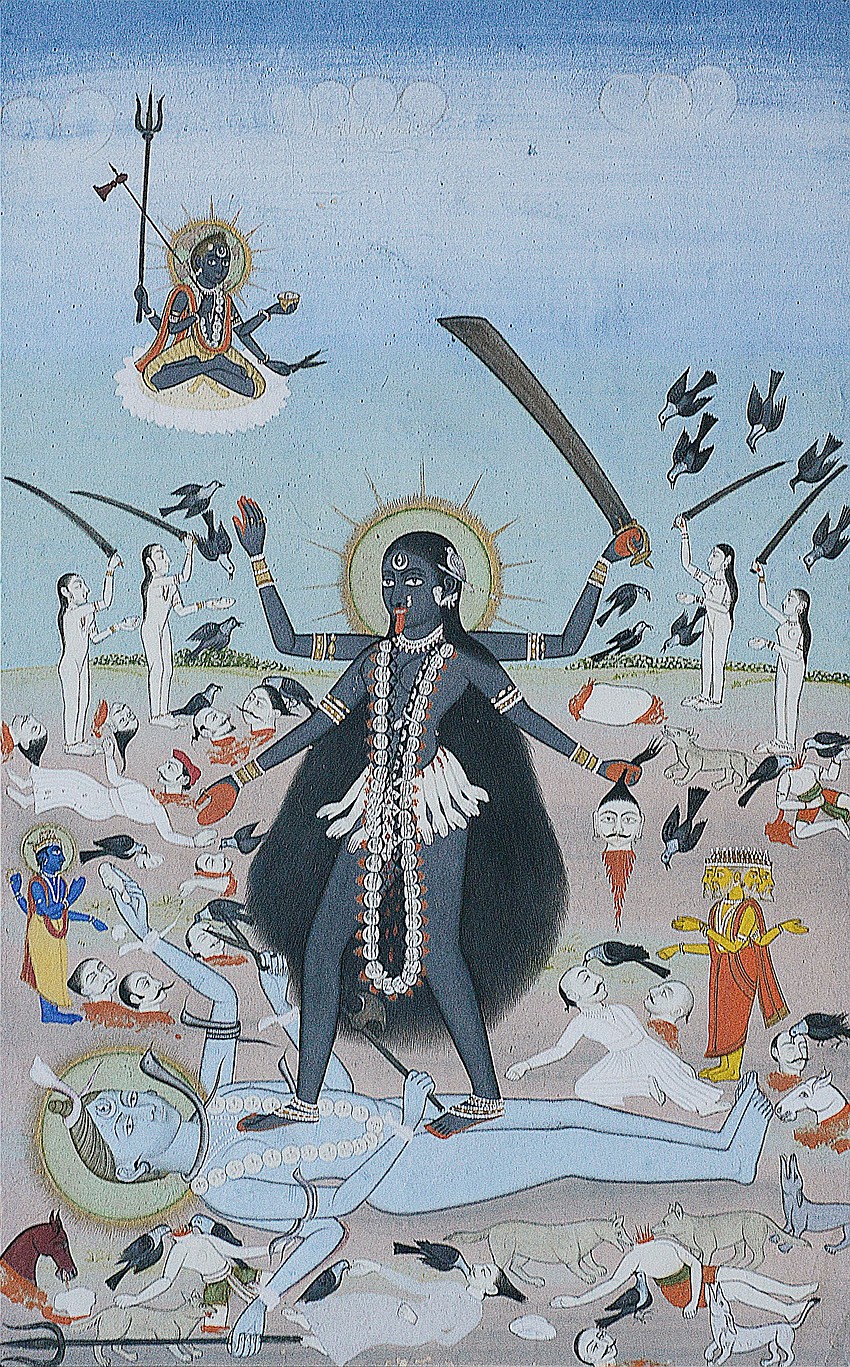

And on the other, there’s a goddess going full Day of Judgement.

The entire human and divine condition is on display at “Gods and Lovers,” the exhibit centered around centuries of Indian painting and sculpture currently housed at The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art.

The sculptures, some carved in stone and some cast in metal, were collected by the Ringlings in the 1920s. But the paintings are mostly on loan; only one comes from the Ringling’s permanent collection, and 16 come from a loan from a private collection in south Florida. Each of the paintings are small format artworks — also known as miniatures — and they were meant to be held in the hands of people either individually or as part of a book.

“Most of the time, they were collected in portfolios. And they were loose or bound,” says Rhiannon Paget, the Ringling Museum’s curator of Asian art.

“They were designed for someone to sit down for an intimate viewing with one person or a group of people to pass them around and enjoy them in that kind of situation. Not the way we have them framed on the wall.”

You may notice that the paintings come from a variety of locales across the Indian subcontinent, and they were all created at points in between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Some have raised surfaces, and others have wallpaper type borders around them, but they all depict famous cultural tales.

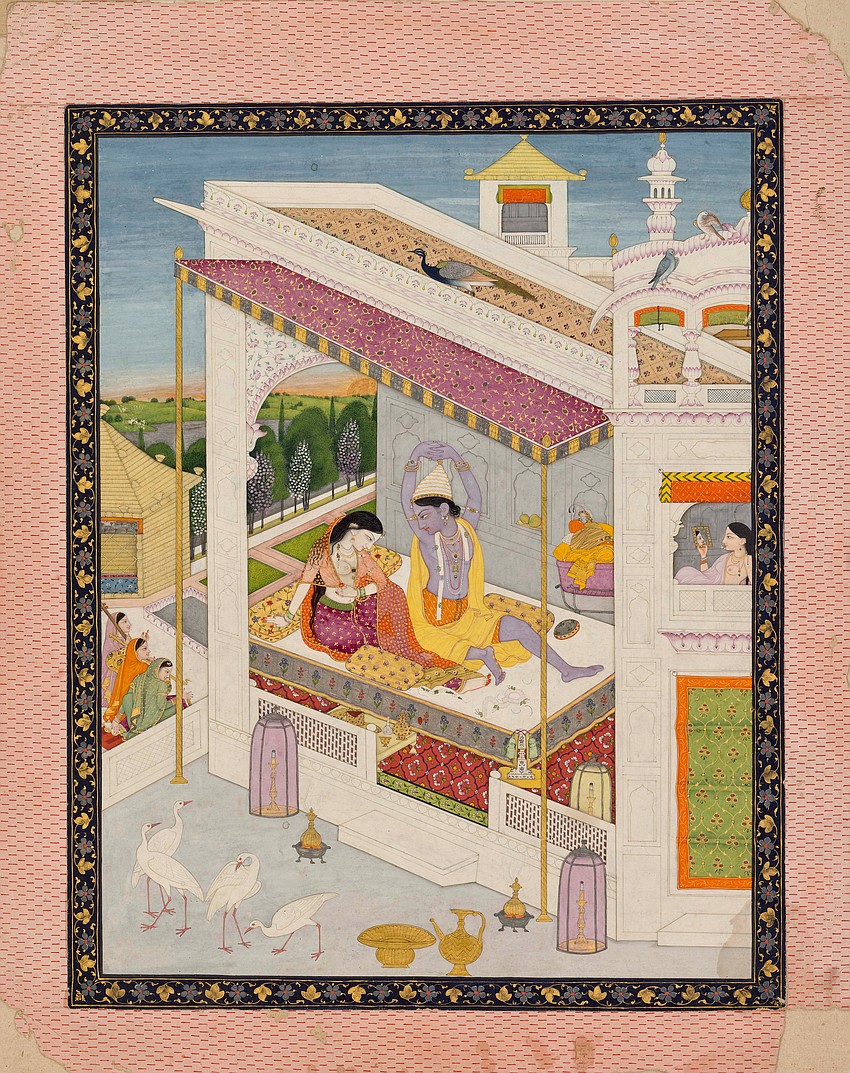

One series of paintings depicts the Ramayana, an epic written in Sanskrit that brings Rama on an arduous journey from exile all the way to his eventual return and coronation as King. Another series depicts the romance of Radha and Krishna; you see the lovers in repose after a night of passion, and in another painting, you see Krishna standing up to be married.

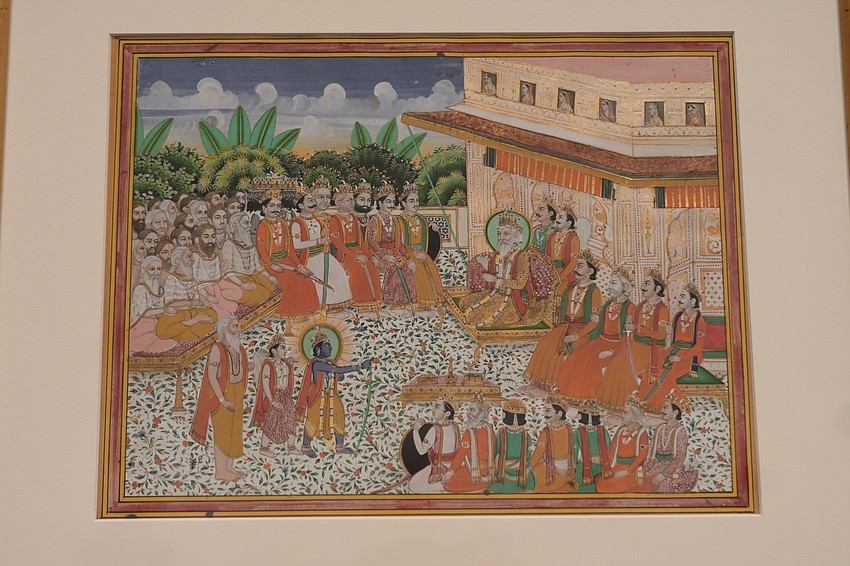

A third painting, made with opaque pigments and gold on paper, shows Krishna being received by Raja Bhismaka of Vidarbha.

This painting, believed to be made in Rajasthan at some point between 1860 and 1880, tells the story of Krishna’s betrothal to Rukmini.

“He has a lovely daughter he wants to get married,” says Paget of the Raja in the painting. “He holds a ceremony in which he invites all these eligible suitors, and the idea is he's going to choose the most worthy one. Krishna shows up, and of course he’s going to be the one but his enemies intervene and put an end to him marrying the beautiful daughter. They sort of secretly scheme to get this other guy to marry her. But she's seen him already. It's too late.”

Collectively, the paintings and sculptures tell the story of melding cultures and religions, and the style of art in the exhibit shows how the ideas and arts spread throughout India over centuries.

Paget says that the Mughal Empire, which ruled over northern India from the 16th through the 18th centuries, played a major role in diffusing artistic techniques and methods. The brought in painters from Asia, they trained local artisans and they funded ateliers for art to be created.

Eventually, those artisans brought their newfound skills to different cities.

The paintings in this collection, says Paget, would all have belonged to wealthy families. They would’ve been prized possessions, which explains why they’ve remained intact and vivid all the way to this day.

“If you think of the climate in India, it's high humidity and cold winters, especially in the north. So pretty brutal,” says Paget. “Some of the paintings do show condition issues like they lose flakes of paint and that kind of thing.

"But these were precious objects. They were cared for.”

There’s more than just romantic epics and tales of weddings at the exhibit.

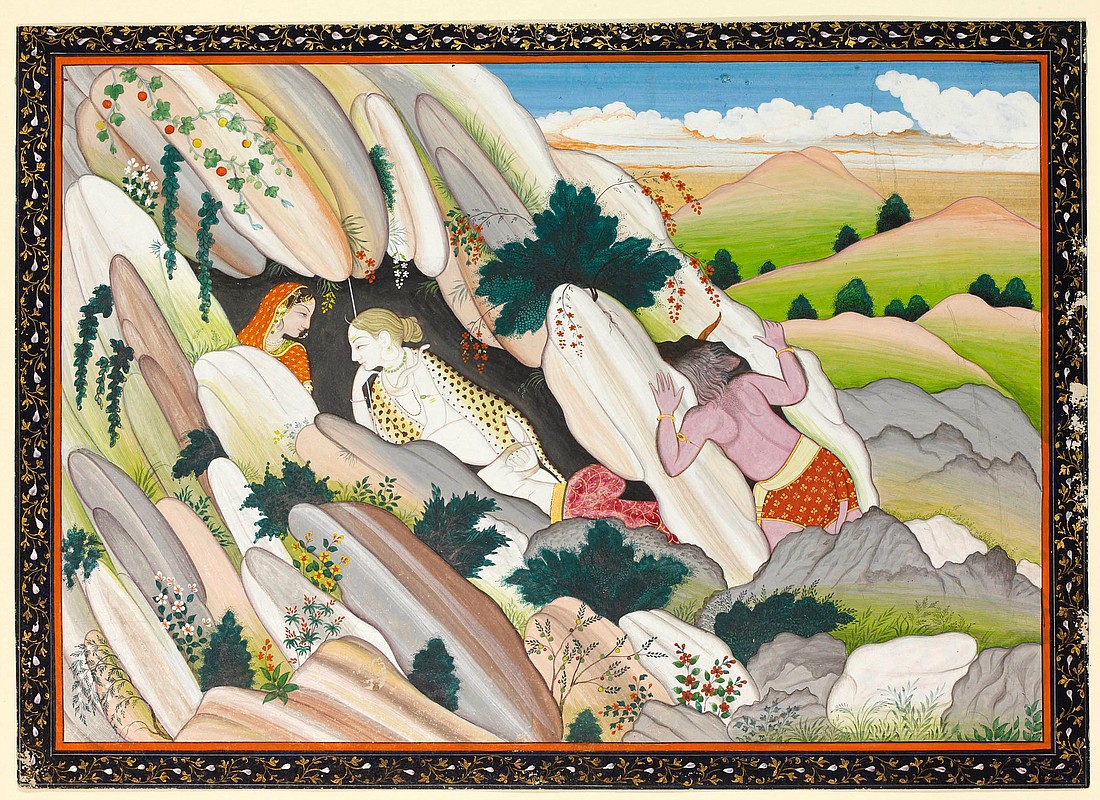

There’s also multiple depictions of the goddess Kali in full destruction mode; in two different paintings, she’s standing on her lover Shiva’s chest, holding a sword in one hand and a severed head in another. In another painting, the one created in Himachal Pradesh between 1830 and 1840, there’s a scene depicting a secluded Shiva and Parvati being spied upon by a jealous demon.

“Shiva and Parvati are hiding out in the mountains,” says Paget, describing the story told in the painting. “This demon, Andhaka, hears that a beautiful woman is hanging out in the mountains with an ugly old sage. His minions tell him, ‘If you want to be the greatest, you need the most beautiful wife. There's this woman in the mountains and she belongs to this old sage. Marry her.’

"So he sends out emissaries to negotiate with Shiva to hand over this beautiful woman and he answers them in riddles and mocks them as they go back to the demon. And the demon is kind of insulted.”

Another series of vividly illustrated paintings shows Indian musicians playing instruments that are now hundreds of years old.

The sculptures included in the exhibit come from a variety of different religions and philosophies; Paget says there are Hindu, Buddhist and Jain sculptures included. One sculpture, made of red sandstone, is believed to have been created in Mathura or Rajasthan all the way back in the 4th or 5th century.

It depicts a figure seated on a lion’s throne, and both its head and its hands have been conspicuously removed from the body.

That’s not really that rare, says Paget; because India was the scene of centuries of religious conflict, much of the sculpture from the region has been irrevocably altered.

“The story of Indian statuary is kind of the story of desecration,” she says. “This has been going on for centuries.

"You've got waves of invasions, different people coming in and taking over an area. They sometimes desecrated things. And also temples fell into disuse because the city kind of changed. And sometimes they would repurpose sculpture that was there.”

Paget says the Ringling has had two prior shows of Indian art in her tenure, and Gods and Lovers will remain on display into the last weeks of May 2023.