- May 8, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

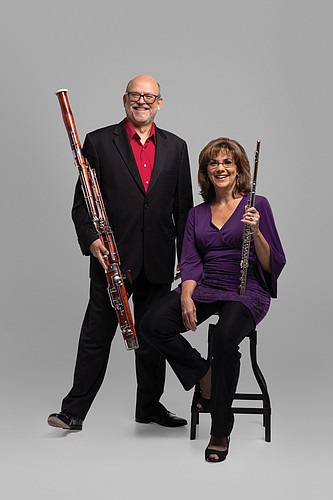

Betsy Traba can still remember the first time she heard her future husband play the bassoon.

The year was 1993, and she had just arrived in Sarasota to join the Florida West Coast Symphony. The orchestra was rehearsing Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, a piece she was quite familiar with, when she heard a texture she had never heard before.

Decades later, she laughs when she hears it described as love at first sound.

“I had heard that solo played many times,” says Betsy. “But he started to play, and his tone was so much richer and so gorgeous. I literally did what you’re never supposed to do in the orchestra: I turned around to look. You’re never supposed to turn around and stare at somebody when they’re playing. But I did. I thought, ‘Wow, who is that bassoon player? He’s really awesome.’ That was what drew me first, listening to him play.”

Weeks earlier, Fernando Traba had had a similar experience. He was part of the committee formed to hire new musicians for the symphony, and he heard Betsy play her flute from behind a screen. Neither musician could imagine how their lives were about to change.

The Trabas are still playing with the Sarasota Orchestra, and they’ve raised two girls who have gone on to become Division I college athletes. Music has given so much to their lives, but more importantly, it helped lead them to their most important relationship.

"I actually think the relationship — two musicians being married — is easier,” says Fernando. “When we goto work, it’s not like we’re talking to each other. We’re part of a team. We have to contribute. The unifying element is we both love music. That’s what brings us together. When we go to work, I don’t think of Betsy as, ‘Oh my gosh, what happened with the washing machine?’ We’re working on a common goal, the music.”

Right now, the Trabas are working on the Be Mine program, a Valentine’s Day themed selection that will have five showings at Holley Hall. But the truth is that their lives and their career journeys have been passionately enhanced by their love for music and each other.

For Fernando, who was born in Mexico City, it’s been a circuitous path to Sarasota.

His father, who had been born in Spain but immigrated to Mexico as a refugee in 1939, taught him how to play the bassoon, and Fernando earned his first professional orchestra position at age 16. But he had to leave Mexico to pursue his dream and get better at the bassoon.

The position he had in Mexico was a dream in itself. The orchestra was subsidized by the government, and Fernando could expect to play there 30 years and retire with a pension. But he knew that if he wanted to improve, he had to leave home and pursue further education.

“I left that amazing job. I would’ve been retired 15 years ago. And I gave all that up because I saw what was possible,” he says of his trajectory in music. “When I think of living in Mexico for the rest of my life, I could not have imagined the amazing life that I’ve had.”

Fernando followed his passion, studying first at the Cleveland Institute of Music and then at Juilliard in New York. He took those course in a second language, and he jokes now that he kind of sounded like Tarzan in his early attempts at speaking English.

But he wouldn’t be denied. Traba’s skill and determination took him first to Portugal and then to Spain, and a few years after that he found himself moving to Sarasota in 1992.

Betsy, meanwhile, had been on a similar odyssey. The principal flutist says she is the product of an excellent public music school program in Ohio, and then she studied at Baldwin Wallace University and at the Manhattan School of Music. At one point, says Betsy, she crossed paths with Fernando but didn’t know it.

“We did discover that he actually came in and subbed in my college orchestra in 1981 or 1982,” she says. “He was on the contrabassoon which is an enormous instrument the size of a coffin. I remember him arriving because he arrived late to a rehearsal, and that was a big no-no. He was a sub, so the conductor grumbled and let him in.”

Betsy, like Fernando, had to move to Europe to pursue her career after college.

She played for three years with the Hofer Symphoniker in Germany before returning to the USA in 1990. Three years later, she would move to Sarasota, a place she has called home ever since.

The Trabas didn’t begin dating right away; they both had relationships but ultimately wound up drawn to each other. And they both say that holding the same career made navigating their relationship a little easier, especially when it came down to managing their time.

“Nobody makes plans for a Saturday night because nobody’s ever free on a Saturday night,” says Betsy. “Friday and Saturday nights are always booked for a nine-month period. If you want to plan a family outing, it almost always has to be on a Monday. That’s our day off.”

“And that’s the day I teach,” adds Fernando.

So how did they make it work when they were trying to raise children? By understanding the importance of division of labor and making sure that they both had time to themselves. Betsy says that they “completely co-parented” and that it took a lot of coordination.

At one point, she says, they really only had time to talk when they were in the car on the way to a rehearsal or a concert. At home, their time was devoted to raising their children but also finding a way to carve out some rehearsal space for their burgeoning career.

“If we’re playing a week’s worth of concerts where he has to play The Rite of Spring — which is one of the most difficult bassoon parts in the repertoire — I know he needs space," says Betsy. "I know he needs time at home with his instrument. He needs time to practice. He needs time to make reeds. Similarly, if we’re playing “Daphnis and Chloe” or “Prelude to Afternoon of a Fawn” — some of the repertoire that’s really hard for a principal flutist — he knows to keep a wide berth. And he doesn’t resent it. We understand the pressures that each other is under.”

Both Traba daughters, Isabel and Mercedes, eschewed the family business. Isabel is a swimmer at the University of Miami, and Mercedes swims for Vanderbilt University. Back when they were learning their strokes, Betsy said the schedule required maximum coordination and cooperation.

“They had practice at 5 a.m. every day before high school,” she says. “We were getting up at 4 a.m. to drive them down to Potter Park. Get home from a concert at 10:30, go to bed at 11:30, get up at 4, drive kid number one to the pool. Fernando would get up at 5 to drive kid number two to the pool and pick up kid number one.’”

Things didn't get any easier at night. Betsy says that the couple required five babysitters at one point because none of them could individually handle the Trabas' chaotic schedule. There were nights when one babysitter had to hand off to another because both Betsy and Fernando were otherwise occupied.

And even at home, they filled different niches.

Betsy took on the task of making sure everybody got their work done and out of the house on time; Fernando became the easygoing father figure, the parent likely to sooth his daughter to sleep by taking her for a late-night bike ride. Fernando handles the cooking, which Betsy says was a requirement for any relationship.

“I wasn’t going to marry anyone unless they liked to cook because I can’t stand it,” she says. “He’s a night owl. I’m not. He’s an introvert. I’m an extrovert. He loves technology. I have a not great relationship with my computer. Mostly, he’s the kind of person who can focus on one thing and become completely immersed in it body and soul. I’m much more constantly have 16 things going on at the same time."

The opposites attract mentality even manifests in how they listen to music.

Fernando is always listening to music; he listens in the car and he listens when he’s in his studio making reeds. It feeds his passion. But for Betsy, she needs some time and space where she can get away from it all.

“When I’m away from work, I just want quiet," says Betsy.

"I don’t want any music around me. If I have the radio on in the car, it’s NPR or it’s the news. If he’s been the last one to drive the car, I turn the car on and there’s immediately an orchestra blaring in my face.”