- July 13, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Dan Houston had a lot of work to do before he could ever sit down to paint.

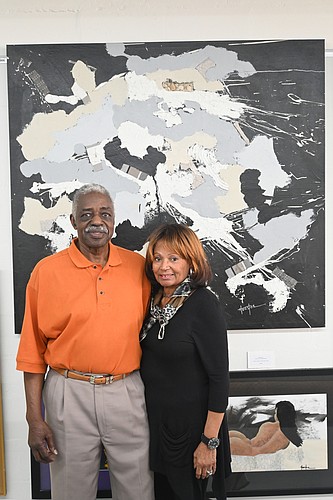

Houston, who runs the newly placed Architectural Wall Decor Art Gallery on Fruitville Road, came into his new space with an artist’s vision and the practicality of a contractor.

He didn’t just want his space to be an antiseptic gallery. He wanted it to be an artist’s studio and a welcoming environment for any potential customers who walked in off the street. So he spent time building it to his own specifications using his own hands.

“My former career, I was a building contractor,” says Houston, who is now an abstract expressionist painter in addition to running his own gallery space. “It took two weeks for us to build all this out and for me to paint the walls and the floors. All that stuff."

Houston, in this case, is being modest. He’s lived many lives prior to becoming an artist. Sure, decades ago, he studied art at multiple schools in Manhattan. But then life got in the way, and he spent decades raising a family and working in other fields.

Houston worked in the meatpacking industry, and he briefly had a foray in advertising. He wound up going to business school and marketing art, running his own gallery but publishing other artists. He got into the construction business, which helped put his children through college. And then, once his kids had completed school, he returned to his first love.

“I hadn’t had a paintbrush in my hand in 20 years, other than a paintbrush to paint houses,” he says. “I took a bedroom in our house, took the carpet out and got an art table and materials, canvases and easels. I didn’t know where I was going to start or what I was going to do, but I just knew that I wanted to do it. As soon as I started painting, what came out was abstraction. I had never had any training or inkling to do abstract. I was trained classically in art school.”

Houston, when he first started out in 2005 or 2006, said he unintentionally was channeling famous artists he had seen, such as Jackson Pollock. But the more he worked, the more his own style emerged.

Over time, he built up a wealth of material, but something in his life was still missing.

And it turns out that the element he was looking for was living in Sarasota.

Houston had met Judith Turrentine decades ago when living in Houston, and they had dated and really connected with each other. But then they fell out of each other’s lives, and Houston discovered a few years ago that they had a friend in common.

He reached out to Turrentine, and the chemistry they had then was still clearly palpable.

“She was was living here,” he says. “We agreed that I would come visit. I came down for 10 days, and she made a hell of an impression. I went back home and made arrangements to start selling my house. I was going to move to Sarasota. I had kids and grandkids all living in Houston. I had to break it to them that Daddy is leaving town. And that was difficult.”

He moved a few years ago, bringing with him his backlog of work.

And Turrentine — who now goes by Turrentine-Houston after their recent marriage in December — began looking for his first space. They found a place on 10th Street but ultimately found it didn’t have enough foot traffic to function as a gallery.

“He had just come here,” says Turrentine-Houston. “I was running around looking for studio space. I was so enamored with that street and those garage doors. There were other businesses there, but I knew nothing about the art world. I wasn’t dealing with walkup traffic or people passing by. It had a space of 400 square feet that we thought he’d use as a studio.”

And he did; Houston estimates that he painted about 70% of his work in Houston before moving to Sarasota, and he did a fair amount of his work in his 10th Street space.

Now he has an integrated space where he can not just work but show his work in style. As you walk around the gallery, you'll recognize a stunningly wide amount of styles and materials. There is no limiting factor to his compositions; some are inspired by unseen explosions and gaseous eruptions in outer space, and some come from childhood ice fishing days with his dad.

“I’m always emotional,” says Houston. “There’s always something going on in my head or in my life that’s distracting.

"I have to turn a switch off so I can go the place I want to go. But I’m very fortunate that I’m with a woman who doesn’t hamper that, who doesn’t feel she’s missing out on my time and attention. If I can take care of her needs, then I feel the freedom to paint. Besides her, the only other real consideration that I have is my children and my grandchildren.”

Turrentine-Houston, incidentally, had no idea he was an artist when they first met.

But it’s become an all-consuming passion that propels his entire life. Houston says he pretty much constantly works, and he doesn’t know what a piece will look like until it’s completely finished. So if his art is abstract — and if he’s not sure what it will look like until it’s done — how does he know when he’s finished his work on any given piece?

“I know when to stop because I know where I’m heading," he says. "When I get there, I feel it. With everything I do, I’m thinking about the next thing I’m going to do. And the next thing. And when I get to that third next thing, I say, ‘It’s finished.’”

The artist says he generally conceives more than one piece at a time, but he’ll only work on one until it’s finished. Sometimes, he’ll break away to go shop for material for his next piece, but he does that to clear his mind a little from the task he’s already begun.

“I don’t like to work when I’m uptight or pressured or need to have money,” he says. “I paint when I have time. I’ll say, ‘I need two or three days worth of time to work on this.’ It may not be six hours every day, but I need to block out some time. And if I can’t block out some time, then I don’t start until my head and my activities clear up so I can put that type of commitment into a piece.”

The gallery is already open from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday to Saturday, but it has an opening reception scheduled for March 15.

So where did the name of his gallery come from?

Was the artist tempted to put his own name on his space just like he does on his artwork? Not even for one second.

Houston says that when an architect builds a building, they usually only build the structure. Afterwards, interior decorators and artisans put on the finishing touches to make it a home. Houston wants architects to think of him when they finish erecting their buildings.

“When a person buys a home or walks into an empty building and looks around and says, ‘What am I going to put in here besides a couch or a table?’ I want them to think of me,” says Houston.

“Art should make you feel good. You should be able to fall in love with it. When you walk out of your bedroom and at the end of the hallway is my painting, I want there to be a smile on your face. I want you to feel that you and this painting are both in a space that makes you connect. That’s what I want my work to project.”

There’s a natural push and pull for Houston; he wants to keep creating work, and he wants to brighten people’s lives.

Houston says that he wishes he could keep every single painting he’s ever done, but he only has so much wall space at his home and gallery and no inclination to stop painting.

“It’s really hard to sell all of my work because there are pieces that are here that I really don’t want anyone else to have,” he says. “But I don’t have a house big enough and I don’t intend to buy a house big enough to house all the work that I can produce.

"So I have to share it, and I don’t mind sharing it if I believe it’s in a loving environment, a respectful environment where the person who wants to buy it feels good about it. There’s a reward going on there — even if I don’t get paid every week for producing work, I know that when this piece goes to somebody’s house, whoever buys that is going to be happy. That’s good enough for me.”