- April 19, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Do you think improving and expanding roadways in the Sarasota region will improve things? Or make them worse? Do you think making it easier for more people to travel just causes, well, more people to travel, and soon congestion is just as bad as ever? If so, what is the point of improving Sarasota’s road network?

People often say that improving roads and adding capacity to allow more travel will lead to new and additional traffic and not improve anything. It’s “we can’t build our way out of congestion,” or “don’t build it and they won’t come.” Transportation experts call this the principle of induced demand.

At its worst, “don’t build it and they won’t come” is like stopping school construction to solve classroom overcrowding. At its best, it is an often-observed reality that without road pricing to match supply and demand, sometimes not all of demand to use the roads can be met, which results in congestion. But while it is true in some narrow contexts, it is far more often misused as a one-size-fits-all justification for resisting roadway capacity expansion. Now, when the pandemic has changed travel behavior, some permanently, it’s time to reconsider this old saw.

Let’s imagine we made major improvements to Fruitville Road between the I-75 and downtown, with synchronized signals and real-time active flow management systems as well as redesign and restriping to allow an additional reversible lane to expand capacity in the direction of the rush hour. But after a year or two of less congestion, more people are using the road and congestion comes back. Is that project a failure? Most opponents of road expansions would say yes because it did not solve congestion.

But there are five interpretations of what actually happened, and the truth could be a combination of any or all of them.

Growth is happening. One reason more people might be using a new or improved road is increased population, employment, or activity in the area. From 2010 to 2020 Sarasota County’s population rose from 379,000 to 434,000, a 14.5% increase. There are simply more people trying to travel in the region. Specifically, a better flowing major arterial might trigger development near that road rather than farther north or south, which might reduce sprawl and shorten commutes, but also might draw new congestion to the improved road.

People change travel routes. A new or improved road that provides more reliable or faster travel means some people will change their usual travel routes to take advantage of it. This isn’t new travel; it’s just redistributed thanks to better flow. Indeed, some people may have been using narrow roads or neighborhood roads to avoid congestion but shift to using the improved arterial. This is safer for everyone and means shorter or more reliable trips for those changing their routes.

People change travel times. A better and less-congested road will cause some people to change when they travel. An errand or appointment they might have postponed until mid-day to avoid congestion can now be done earlier or later thanks to the less-congested road. This also isn’t new travel, and it has no effect on total travel but enables individuals and commercial vehicle drivers to travel on their preferred route at a better time. A parent may get home in time to eat with the family, attend a sporting event, or proctor homework. A delivery vehicle may be able to deliver products more quickly. These benefits improve the quality of life for everybody.

People change modes. Less congestion might cause some people to stop using the bus or carpooling and to drive instead, thanks to reduced congestion. This isn’t new travel, but it is new vehicles on the improved road. Sarasota County only about 1% use transit to get to work, but nearly 12% carpool, at least before the pandemic. Based on national data, working from home has likely cut those numbers substantially, and some of that will be permanent. So, there is not a lot of transit travel there to shift to driving alone when roads improve. Moreover, supporting congestion to induce people to use transit or carpool is terribly ineffective and makes people’s lives less convenient. Transit use would have to increase 14 times just to absorb new travel from population growth, when in fact it is barely able to hold on the riders it has.

People travel more. Some fear that reduced congestion due to road improvements will cause some people to travel who otherwise would not have, or to travel farther, perhaps living farther out of town or going farther to shop, than they would with higher congestion. This is indeed added travel, and since this can have some environmental impact, they might argue it is better to leave the roads be and let congestion constrict this potential additional travel. But if improving or adding a road causes people to travel farther to work or shop or enjoy recreation, that means before the road improvement they were settling for something worse, and that they get real benefits from more mobility. This has traditionally been a desirable outcome of better transportation created by new connections or new capacity.

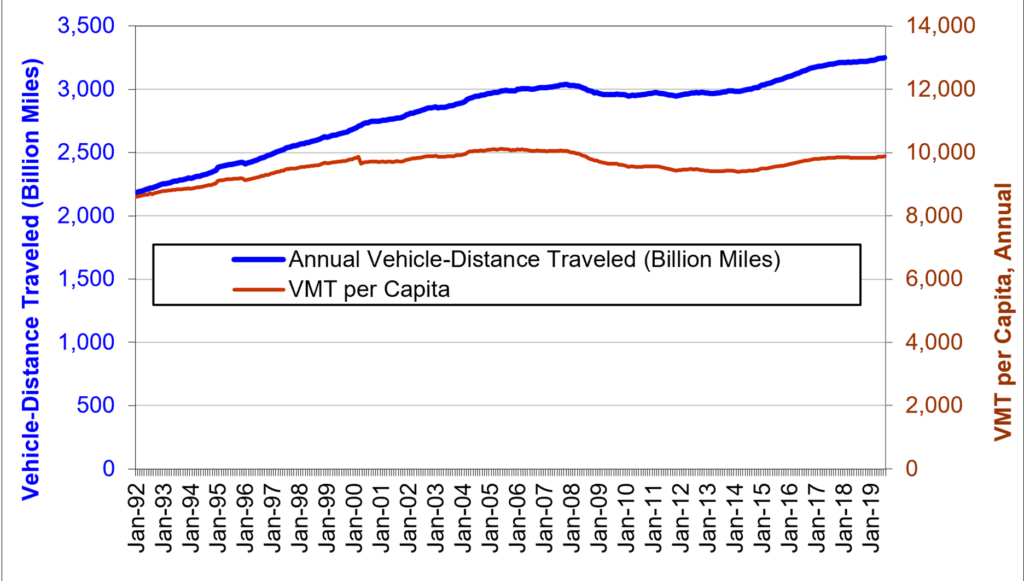

A few other facts about travel to keep in mind. Nationally, we have not tested the hypothesis that we cannot build our way out of congestion, and for decades demand has grown despite roadway capacity per capita shrinking. Arguably, demand is being induced despite a lack of new capacity. However, in recent years vehicle-miles of travel per capita have moderated and not returned to the peak levels of 2004-2007.

At the same time, rising telecommuting instead of work travel is likely to impact traffic inducement. The work-at-home share has grown from 2.3% in 1980 to 5.9% in 2019 and dramatically accelerated with the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in expectations that post-COVID work-at-home shares will be over 10% and increase as the share of information jobs in the economy increases. E-commerce, distance-learning, online business transactions, and telemedicine are also likely to grow, moderating any increases in travel.

Finally, a growing share of roadway travel (almost 30%) is not household-based person travel but commercial and service vehicle travel responding to business, government and household needs. This includes police, fire, ambulance, mail, school buses, delivery vehicles, and the myriad of services we use — from lawn, insect, pool and repair services and service visits such as home health care, real estate agents and decorators. This travel doesn’t reduce when congestion rises, it just becomes more expensive and worse for customers or those calling for emergency services. Road improvements and better mobility help us in many ways besides our own travel.

It is transportation officials’ responsibility to vet and challenge proposed projects based on a full analysis of the impacts. Studying design options to improve transportation outcomes and reduce the effect on neighboring and broader communities is likewise a worthwhile endeavor. Accepting the myth that improving roads just induces more demand and congestion will soon return ignores the much more complicated realities of travel supply and demand, and the many and broad benefits of mobility improvements.

Adrian Moore, Ph.D., is vice president at Reason Foundation and lives in Florida, and Steven Polzin, Ph.D., is a former transportation professor at the University of South Florida.