- January 15, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

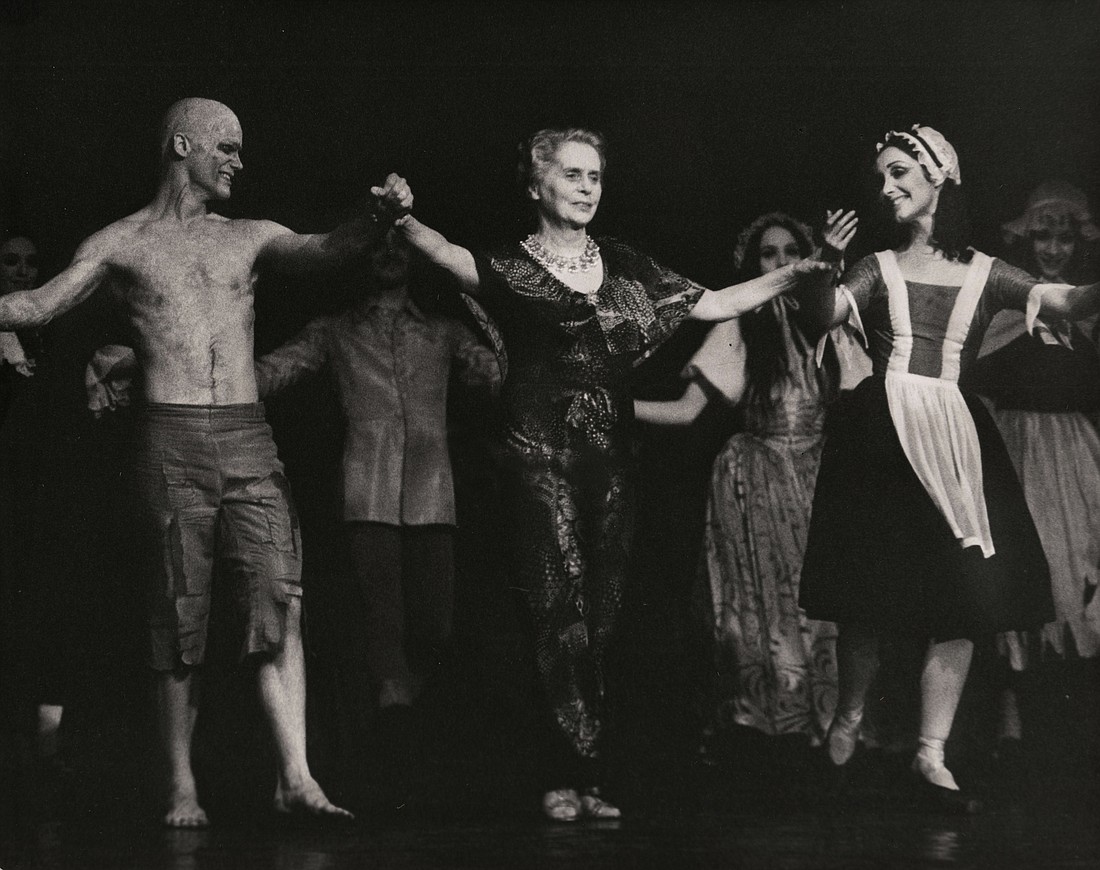

"The Rake’s Progress" isn’t just a ballet for Margaret Barbieri. It’s a time machine connecting her to her illustrious past as a dancer and a talisman for future generations to peek at and see where the roots of their craft began.

For Barbieri, the assistant director of the Sarasota Ballet, there are few programs that are more personal.

Barbieri was directly tutored in the role by its creator, Dame Ninette de Valois, and she also worked closely with Alicia Markova, the first ballerina to play the Betrayed Girl.

“I can’t believe sometimes how long it’s been,” says Barbieri of her decades-long connection to the ballet. “When I look back at the number of years, it suddenly makes me feel very old.”

When Barbieri first met de Valois, she was a graduate student at the Royal Ballet School in London in the 1960's and her mentor had recently retired from being director of the Royal Ballet. De Valois had first choreographed "The Rake’s Progress" in 1935, and decades later, she was still working on the precise gestures used to accentuate the dancers’ movements.

“I always tell the dancers. There was one particular thing, the entrance of the Betrayed Girl,” says Barbieri. “One day, she wanted the hand at the side of the face. The next day, it was at the front. I got so confused. What am I going to do for the performance? And I realized after that it was because I wasn’t doing it well enough so she was trying different things. That’s why she kept changing it day-by-day. She was trying to get the character to look real.”

"The Rake’s Progress," interestingly, is based on a series of paintings by William Hogarth that illustrate the profligate spending and downfall of a man in society. The protagonist is the son of a rich merchant who wastes his family fortune on luxury, prostitution and gambling.

Ultimately, the subject of the paintings — and the star of the ballet — winds up imprisoned and institutionalized in a mental hospital. The ballet has to work up to that, though, and Barbieri said that the show brings the audience on a frantic ride of emotional highs and lows.

“They truly are wonderful roles,” says Barbieri. “For the Rake, it’s a real challenge both acting wise and physically. By the time you go mad, you’re physically distraught. And then you have the complete contrast, where you have the only girl en pointe, which is The Betrayed Girl.

"She has an innocence to her, a great love for The Rake. She’ll do anything. She gives all her money to try to save him, and then she actually visits him in Bedlam.”

The Rake’s Progress is one of three acts to the Sarasota Ballet’s Love and Betrayal program, which will take place Jan. 28-31, and the two principal dancers — Victoria Hulland and Ricardo Graziano — have both performed in it before. But both Hulland and Graziano are taking on new roles; they performed smaller parts back in 2016, and they’re still learning how to make the performance their own.

“I was pretty young the first time I did it. I think I was 21 maybe,” says Hulland. “That makes it interesting to revisit so many years later. I’ve found that my muscle memory is going back to how I did it when I was 21, and I’m like, ‘No, I can’t do it like that anymore.’

“I need to bring new things to it. I’ve changed. I’ve matured. How can I develop this character even more so? It’s great to rethink everything. It’s good to have that muscle memory because it makes learning everything so much easier, and then you can dive even more deep into it because the choreography is already there. Now you just need to make it more expressive.”

Graziano, who plays The Rake, said he has danced in this ballet twice previously, and like Hulland, he said it wouldn’t be possible to perform this work without Barbieri’s input. The whole character arc, said Graziano, allows him to act as well as dance, and he said that by the time the ballet ends, The Rake has been through an emotional and physical ringer.

“I do love the mad scene,” says Graziano. “That’s definitely my favorite scene when he ends up losing all his money and he ends up in prison and he goes crazy. It’s where I do most of the dancing but there’s just so much acting and it’s so intense. It’s the best music and the best scene in my opinion.

"The other mad people in the madhouse, their choreography is so amazing. The man with the rope and the man with the violin, the guy playing cards. It’s so well choreographed. It’s insane to think that was created that long of a time ago.”

Of course, for Graziano, there isn’t much room to collect his breath.

The scenes at the end are heart-rending, he says, because you’ve been on an emotional journey in 30 or 40 minutes.

“It’s really difficult to tell the story without exaggerating and while still doing the steps,” he says. "You go through a whole costume change really quickly in the wings just before the madhouse.

"So it’s almost like you never stop. You’ve just lost all your money. You go into this prison. And you start slowly getting crazy. You have to build up to it, because when you get to prison you’re not crazy yet. It’s not only going crazy; it’s one of the most emotional scenes in the ballet. Victoria joins the scene as well as the Betrayed Girl. You feel bad for him. You feel bad for her. And there’s this love connection. It’s difficult but it’s very fulfilling.”

Dame Ninette de Valois died in 2001 at the ripe old age of 102, and Barbieri has been proud to teach her work across an ocean from where it originated all those years ago. But in her mind’s eye, she’s still the ingenue trying fervently to win her mentor’s praise.

Barbieri can recall working on another de Valois production, Checkmate, and how far away she seemed from achieving her goals. She wasn’t originally cast in the role she wanted in Checkmate, she said, but one day she was summoned for a meeting with de Valois.

“I thought, ‘Oh my god, what have I done?’” she says. “I go up to the office and Madame says, ‘Now darling, you’re totally all wrong for the Black Queen. You’re a romantic dancer, but you know what? I think it will be so good for you to do the Black Queen. I will rehearse you in it personally. Every day. It’s got to be more sensual. It’s got to be more powerful. Every day.”

Now, here she is, decades later, passing on that same kind of tutelage to her dancers.

“I love the rehearsal process with Maggie,” says Hulland, performing in Rake for the fourth time. “The style of Rake is so important, and I think that’s why it’s so effective. There are so many stylistic ways you have to hold your hands and arms. It’s not so much these big or grand dance moves that you see in the classics. To have Maggie coaching us so we get that hand position just right, besides stage presence, those little hand positions are what makes those paintings come to life and the ballet so effective for the audience.”

Both Hulland and Graziano said that not only had they never danced "The Rake’s Progress" before moving to Sarasota, they had never even seen it before. And according to Barbieri, really nobody in America had seen it until the Sarasota Ballet began performing it.

The classic routine came with Barbieri when she came to Sarasota, and they’ve returned to it a number of times over the years.

Between the Royal Ballet and the traditions born in Sarasota, Barbieri believes "The Rake’s Progress" will continue to thrive for generations to come.

“I think it will survive a long time after us even,” she says. "It’s an important historical work both because of the subject matter and also because it was choreographed by Dame Ninette de Valois, who didn’t choreograph that many ballets.

“I asked her why she didn’t continue to choreograph; she’s done such fabulous work. And she said, ‘As a director, it was my position to stand back and allow the younger choreographers to take over.’ She chose wisely in many ways, because if she had been choreographing everything, all those fantastic choreographers wouldn’t have done their amazing work.”