- January 22, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

At the age of 23, Dragos Alexandru thought he was headed to the United States within months.

He was not, at least not yet. Although he had talked to the U.S. Embassy about immigrating, it would be four years of waiting for him to leave his home country of Romania; his government did not want him or anyone else to leave. The years in between were filled with harassment from the Romanian government and stress about when (or if) the country would let him leave. It got so bad that Alexandru attempted to defect via an oil ship headed for Houston; he was caught and arrested but ultimately let go with a warning.

When he finally arrived in America at the age of 27, Alexandru said, he realized all the hassle had been worth it.

Alexandru, now 65, was not just anyone in his home country. He had represented Romania in the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics as a rower. It was during his travels as a rower to places like Italy, he said, that he began to realize just how restrictive the communist Romanian government was. It controlled the news you consumed, the food you ate and the place you worked. One week, Alexandru remembers, in an attempt to save on gas, the Romanian government allowed only half of its drivers to use their cars, the ones with license plates starting with even numbers. The next week, only cars with odd license plates were allowed to be on the road.

"It's all one way," Alexandru said. "It's 'follow or else,' and the 'else' is putting you in jail."

When many Eastern Bloc countries announced they would not partake in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics in support of Russia, Alexandru feared Romania would follow suit. He found himself with a choice to make: He could stay and make an attempt at qualifying for the 1988 games, or he could put his rowing career aside and leave, starting anew. He opted for the latter, and he wanted to go to the U.S., even though he knew no one there. He had heard enough stories of achieving the "American dream" that he believed he could make a life here, and that was enough.

"I had no real expectations (for the U.S.)," Alexandru said. "What I did know, for sure, was that it could not be worse than where I was. That's the bottom line. It could only go up."

So he left, or at least prepared to leave. Four years later, he found himself on a train to Rome, where he spent two weeks with other Romanians immigrating to the U.S. in a type of adjustment period, learning about U.S. customs from an English-speaking teacher. He brought little with him other than clothes. After two weeks, Alexandru flew from Rome to Manhattan, New York, where the U.S. had an organization waiting for him, helping him transition. He was given two week's worth of money and a place to stay. He had that amount of time to find a job and a more permanent residence, which he did via a Romanian connection he made in the city.

When Alexandru arrived in Manhattan, he was shocked by many things, but none more so than the choices he found in the bread aisle of his local supermarket. In Romania, people simply buy bread; there is but one kind. In Manhattan, staring at the bread aisle, Alexandru felt overwhelmed. He bought a soft white bread, not knowing that he had to toast it to unlock its full potential. He ate his bread mushy for a while until he figured out the secret. Other things that confused Alexandru at first: coin-operated laundromats and greeting people with handshakes as opposed to kisses on the cheek.

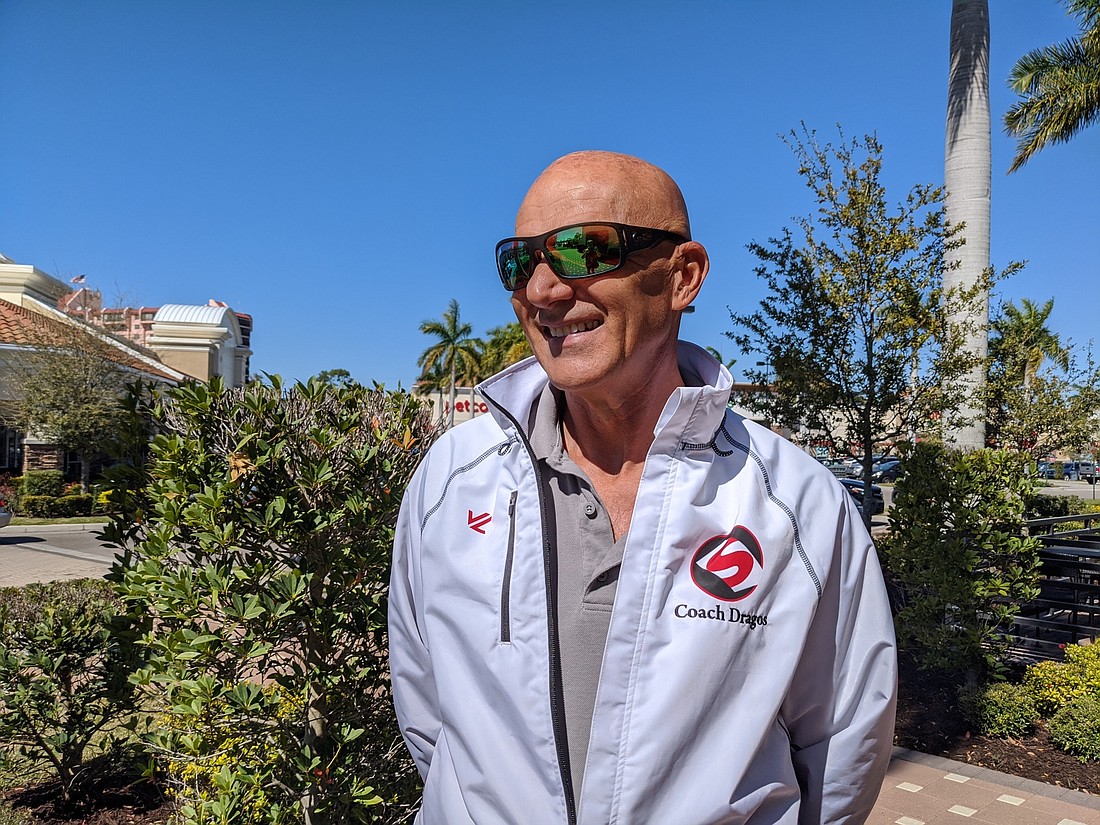

Despite these cultural differences, Alexandru thrived in America. He decided to take classes at Grumman Data Systems Institute and was able to find a job in his field of IT work. He stayed in New York until 2002 when, in the wake of 9/11, he and his family moved to Sarasota. Once here, Alexandru stayed in IT but also became a rowing coach with Sarasota Scullers. He stayed with the program until 2012. He is now the head coach of Sarasota County Rowing Club and assisted in the development of Nathan Benderson Park as a top rowing destination.

Alexandru experienced a personal tragedy in 2007 when his son, George, died in a car accident at the age of 23. Alexandru said his son's death is the only thing he would change about his time in America. In every other aspect, his experience has been more than he ever dreamed.

"You use your brain, and you work hard and you can make it," Alexandru said. "It's not perfect, but no place is perfect. All the good here cannot be pushed out by the bad. Living here is an advantage. Take it."

It is the extent of America's freedom of choice, Alexandru said, that separates it from all other countries, even other well-developed nations. In Europe, he said, people can't sit and talk after finishing their drinks at a cafe on a weekday morning. They will be questioned and told to leave by the staff. In America, you can relax. If you want to move to another state, you don't have to get approval from the government first, you just do it. You can travel any time you want. You can go swim in the bay or visit a gun range.

These are things many Americans take for granted. After growing up in Romania, Alexandru never will — not even mushy white bread.