- July 15, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

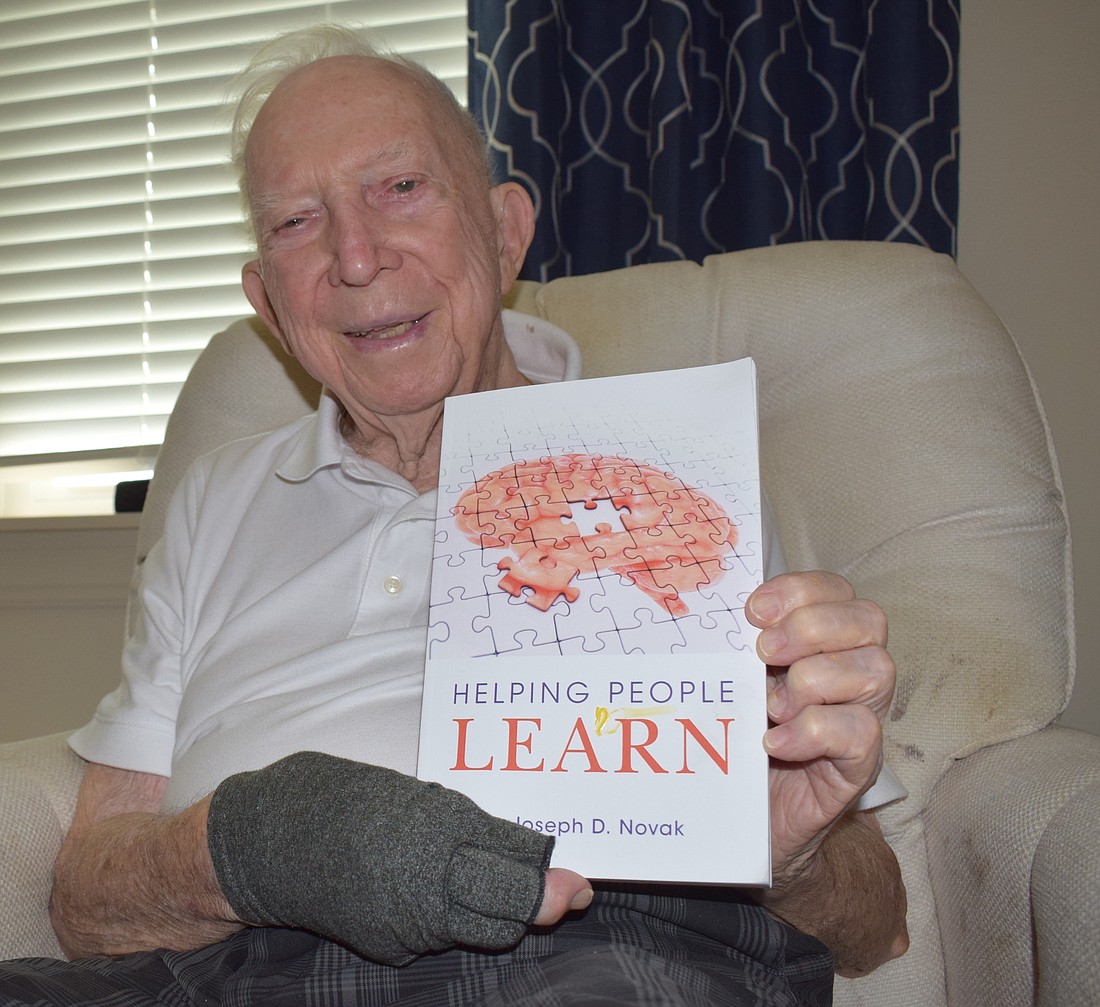

At 91, Joseph Novak sits these days with his easy chair adjacent to one corner of his television in his home at The Sheridan at Lakewood Ranch.

It was a few months ago that his sight had declined to the point where he could no longer do research on the internet. However, he can still make out figures on the television screen, which is right on top of him.

“I can still tell if they are men or women,” he said.

Losing his sight is an incredible loss not only to Novak but also to the world of education. A professor emeritus at Cornell University, Novak is known for his work on human learning, his educational studies, his theories on cognitive psychology in learning and his concept mapping. He has written 41 books on the various education subjects and had more than 150 papers published.

His latest book, “Helping People Learn,” was published by Cambridge University Press on June 30.

Novak sat with his wife, Joan, and pondered his future as an author.

“Helping People Learn” is a summation of more than 60 years of his work as he tried to write in a format “the average person could understand.” But while the work comes natural to him, he needed Sheridan volunteer Dee Humphreys to do much of the typing for him.

Will there be a 42nd book?

“I don’t think so,” he said softly. If another book doesn’t come to fruition, Novak continues to be a human reference book of knowledge when it comes to educational learning topics.

It was back in the late 1950s and early 1960s when Novak started to be bothered by the preponderance of behavioral psychology in learning, or what he calls the “memorize-test-forget kind of education.” His contention was that a cognitive psychology approach was much more beneficial as students learn why things happened instead of just learning that they did happen.

With both science and education degrees, Novak began his teaching career at Kansas State Teachers College in Emporia, Kansas in 1957. But his focus gradually changed to “teaching teachers” as he taught biology and teacher education courses at Purdue University from 1959-1967, and then at Cornell from 1967-1995.

The beginning of his foray into promoting the cognitive psychology approach wasn’t embraced by many of his colleagues.

“Cognitive psychology was considered a far-out view,” he said. “But a lot of the literature at the time didn’t make sense. I thought education could become a science if we would understand how people learn.”

He noted that psychologist B.F. Skinner was the shining start of the 1950s and 1960s with his work on human action being dependent on the consequences of previous actions, and the principals of reinforcement.

“Behavioral learning emphasizes reinforcement,” Novak said. “You repeat things. You know 2 times 2 equals 4, but you don’t understand the concept. You don’t know that (on a ruler) 4 is twice the distance from 2.”

He began writing his books and papers in the 1960s and said he was called an “outcast.”

When he began working at Cornell, he went to the National Science Foundation in the search for funding for his research, but he was rejected.

“My theories were considered a left-field view of learning,” he said. “It was anything but mainstream. The officers of the National Science Foundation were all Ph.D.s, but they didn’t understand what I was talking about. It was so obvious that a 6- or 7-year-old kid would understand, but they didn’t.”

Fortunately for Novak, his ideas started to be accepted in universities around the world. Visiting professors would come to Cornell to learn about his basic concepts that focused not on memorizing information, but to ask why it was happening.

“It is amazing to see how people can get locked into a conceptual view,” Novak said. “You see it in politics. It is hard to see someone else’s view that is so radically different.”

Novak said an example of cognitive psychology learning is when children learn a language through experience, such as living with a relative, as opposed to memorizing words out of a book.

“It stays with them a lifetime,” he said.

When Novak was a child, he learned Slovak in his household in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he lived until he was 23. He and Joan became snowbirds in 1995 after she had open-heart surgery the previous year. They lived half the year in Tarpon Springs and the other half in Ithaca, New York in the Finger Lakes region.

While he was winding down his university career, Novak began to work as a consultant, teaching his concept mapping principals to private companies. The first was in 1993 to Procter and Gamble, which was trying to develop a “wet” toilet paper that could be distributed off a roll.

He met with 18 Proctor and Gamble executives and they explained the problem, that they couldn’t get paper to hold moisture. There was a market for the product in Japan, but they hadn’t been able to deliver.

“We created a concept map in one day,” he said. “They needed chemicals that would retain moisture and they had all these Ph.D.s in the room, but they didn’t have that kind of chemist. We drew a concept map and found they were producing a lot of diapers. They had been working on the project for two years, and two moths later they were marketing it.”

He worked with Procter and Gamble for four years, then branched out, teaching his concept mapping techniques to the Army, Navy and NASA, among others.

Novak moved to the Sheridan in 2019 with help from his son Joe Novak, and his wife Elizabeth, who live in Lakewood Ranch.

His hope is that educators will visit and discuss theories. Any educator who would like to discuss theories can reach him by calling The Sheridan at 313-3213.