- April 11, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

When golf course architect Richard Mandell first toured the Bobby Jones Golf Club complex while preparing to bid on its restoration, he was accompanied by his son, Thomas, who was in seventh grade at the time.

To put into perspective how much time has passed since that first visit, as earthmovers now excavate, haul and push dirt around to reshape Sarasota’s municipal golf facility to its original Donald Ross layout, Thomas is now a college freshman.

“I’m waiting for my five-year pin (from the city),” Mandell joked during a recent visit to the project, one of three he has underway in Florida.

Much has happened since the Pinehurst, North Carolina-based Mandell was tapped to restore the course associated with two of the game’s most iconic names — Jones, the player, and Ross, the renowned architect — attached to it.

As the scope of the project changed multiple times over the ensuing five-plus years, the frequent changes resulting in a series of delays, the club operated as normal until it was closed at the onset of COVID-19. Although golf enjoyed a renaissance throughout the pandemic, the decision was made to keep Bobby Jones closed until it was renovated.

Meanwhile, maintenance operations ceased and the 45-hole property became overgrown.

Back in 2016 when talk of renovating the club began, it had already entered into the death spiral that afflicted many golf courses in the 2010s — declining revenue leading to reduced capital investment resulting in deteriorating conditions prompting reduced play causing declining revenue, and so on.

“When I first visited in 2016, what I saw were declining conditions based solely on a lack of capital being put back into the golf course,” Mandell said. “That is typical of courses that haven't been renovated in 30 years or more. At that time, the newest holes were 29 years old and tired. Yet there were other holes out there that hadn't been touched for a lot longer than that.

“What I saw were lots of drainage issues, outdated golf course features and poor turf conditions.”

Built on a floodplain between Fruitville Road and 17th Street, drainage has always been an issue at Bobby Jones. Water management in 1925, when Donald Ross designed the original 18 holes, was at best guesswork to the extent it was considered at all. Future expansions that added 18 more holes incorporating the original front and back nines into the American and British courses only exacerbated the frequent flooding and persistent wet conditions.

The final iteration of the restoration plan brought Bobby Jones back to the original Donald Ross layout, incorporating modern golf course design, engineering and draining techniques intended to alleviate flooding and waterlogged conditions. Initially scheduled to open this fall, delays in starting work pushed construction into the rainy season causing further delays.

Mandell said he expects to course to open for play in mid-summer 2023, likely followed shortly by the nine-hole short course across Circus Boulevard.

At $12.5 million, the golf portion of the project includes the 18-hole restoration, the adjustable par-3 course, practice facility temporary clubhouse and eventually a new permanent clubhouse and other utility buildings. The golf complex will cover 187 of the 307 acres there, the remainder of the site comprised of a nature park and drainage of canals.

The work is funded by a $20 million city bond, a $3 million Southwest Florida Water Management District grant for wetlands improvement, which requires a 50% local government match; and a $487,500 Florida Department of Environmental Protection grant. Golf revenues are planned to cover course operations and be applied toward the debt service.

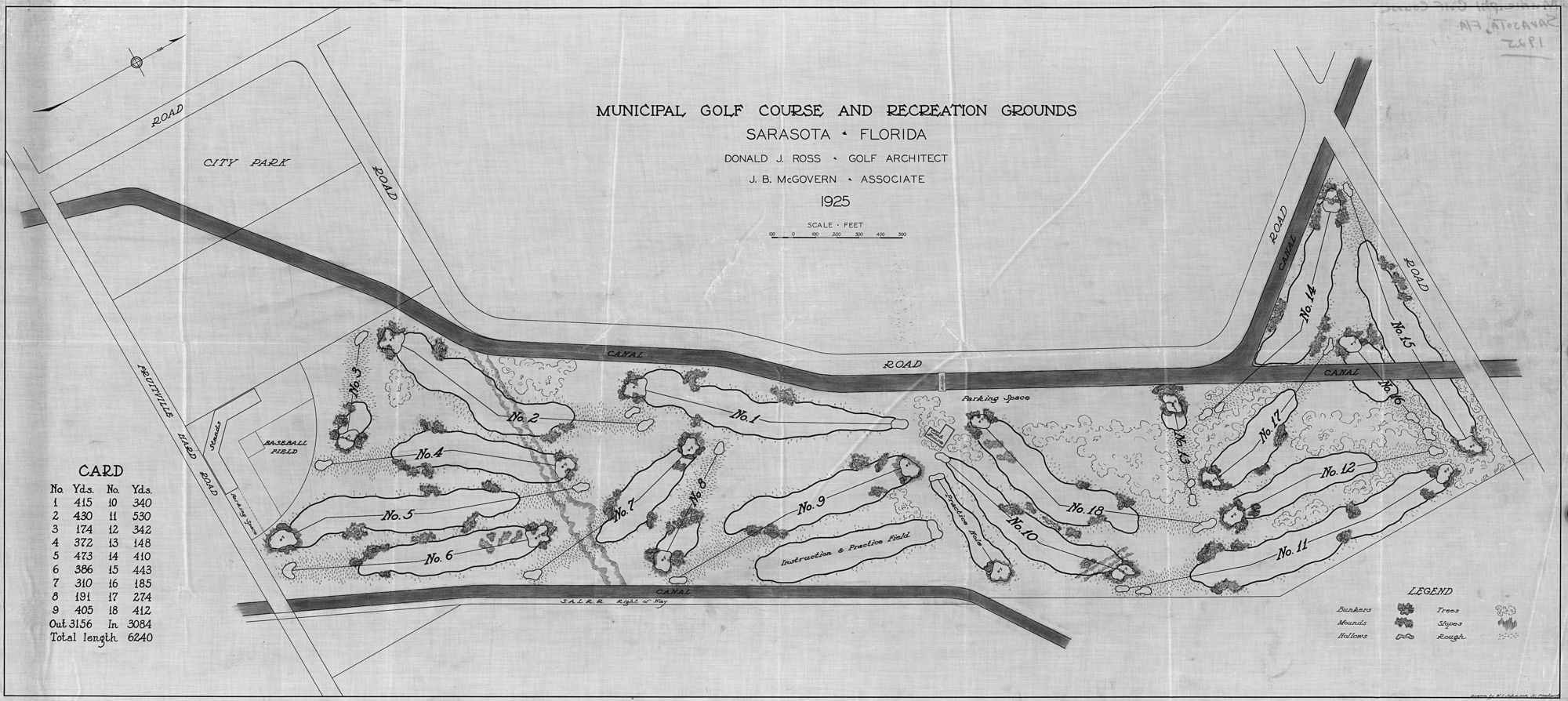

Mandell didn’t have to go far to find the Bobby Jones course layout, which Ross drew in 1925, and the hole-by-hole notes and detail drawings. Just more than two miles from his Pinehurst office is the Tufts Archives, where the drawings are preserved. Mandell is using the sketches to restore the 6,240-yard course as Ross envisioned, but elevations, mounding and shaping will vary from the original in order to facilitate drainage.

“The first step is getting dirt in the right spots and controlling the water and the drainage,” Mandell said. “Then it’s the shaping of the mounds and the construction of the drains.”

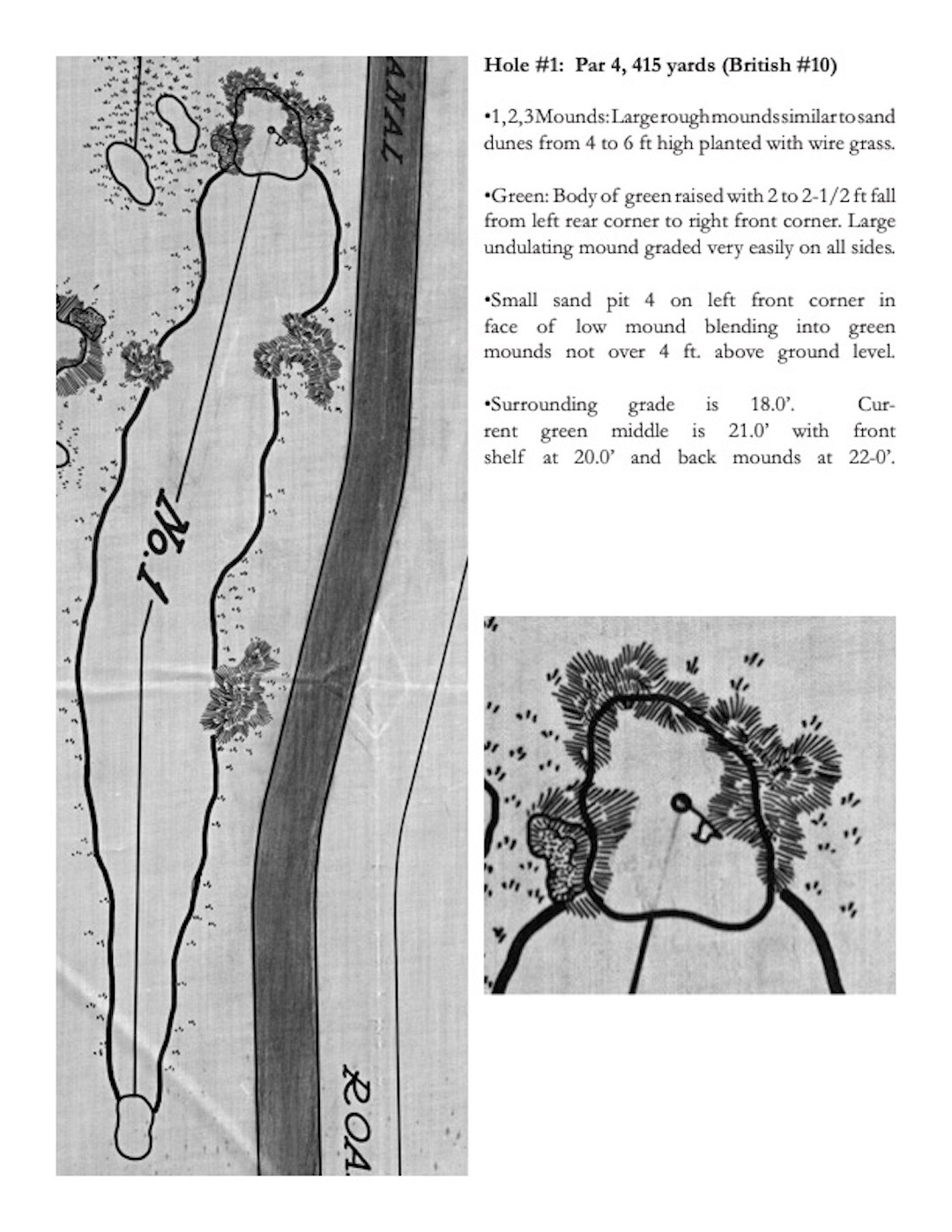

Once rough grading, irrigation and drainage are installed, Mandell and the construction crews turn their attention to arguably the most importing part of this or any golf course, the greens. Here, the Ross sketches are somewhat light on the details.

His notes for the No.1 green, for example, read: ”Body of green raised with 2’ to 2 1/2’ fall from left rear corner to right front corner. Large undulating mound graded very easily on all sides.”

For the par-3 No. 13: “Built-up 3’ at front and 5’ at rear – slight terrace effect. Terrace at left corner 6” below body of green. Terrace effect across front, raise the sides and rear having a slight undulating effect. Long slopes on all sides. Sand pockets 1, 2, 3 on left & right front corner and at rear at edge of canal.”

Mandell mirrored the green shapes and adapted the elevation changes and desired green speeds to the modern game for the recreational golfer. Undulating greens, he said, need not be lightning fast to be fun.

“I will review the slopes every 10 feet both vertically and horizontally to make sure that everything drains properly and they are no pockets and to make sure there are pinnable areas (flat areas where holes can be cut) slope-wise, and make sure there is variety in those slopes,” he said.

Bobby Jones is Mandell’s 11th Donald Ross restoration. He takes personally the task of preserving the legacy of one of the world’s most renowned golf course architects.

“A lot of people aren't aware of Ross, so this is an opportunity to show people why people like me consider him one of the all-time greats,” he said. “I feel almost like I'm a project manager for Ross in this case because I'm trying to implement all the information that we have. Right we only have 26 aerials, which are not that informative, other than it tells us how few trees were out here originally.”

As crews have been removing soil from the nature park area for use at the golf course, they’ve been shaping the wetland as they go.

In addition to drainage from the golf course, the wetland will serve as a natural water purifier as it gradually filters stormwater runoff entering the property from 17th Street and surrounding neighborhoods before it exits at Fruitville Road.

“Within the park, we've created this wetland, and that was always the plan whether it was going to be golf or a park,” Mandell said. “We diverted one of the canals so that we can get the driving range somewhat to the clubhouse, but it also enabled us to divert that water into a pretty expansive wetland. This is where this is a community project in that everyone who's not even a golfer benefits in the sense that his site is a detention for stormwater. Once it comes through the canals and it goes through the wetland and it gets filtered, when it leaves down on Fruitville it's much cleaner. And when it gets to its final destination, Bobby Jones has done its part in cleaning up that water.

“The purpose of a floodplain is to hold water, and it's still going to be that way. The whole front nine was always lower than floodplain, so it’s no surprise as to why it was always wet. Now we're trying to fix that while also providing our service to the city.”

Once areas of the golf course are completed, the fairways, rough, green and green complexes will be sprigged. The grow-in requires six to eight weeks before the course is playable. Areas that can be will be planted this fall, the remainder in the spring. The course will open with a temporary clubhouse and the time frame for a permanent facility remains to be determined.