- November 13, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

“Any sailor who says he hasn’t run aground at least once either isn’t a sailor — or is full of crap!”

“Murphy’s Law was invented on a sailboat!”

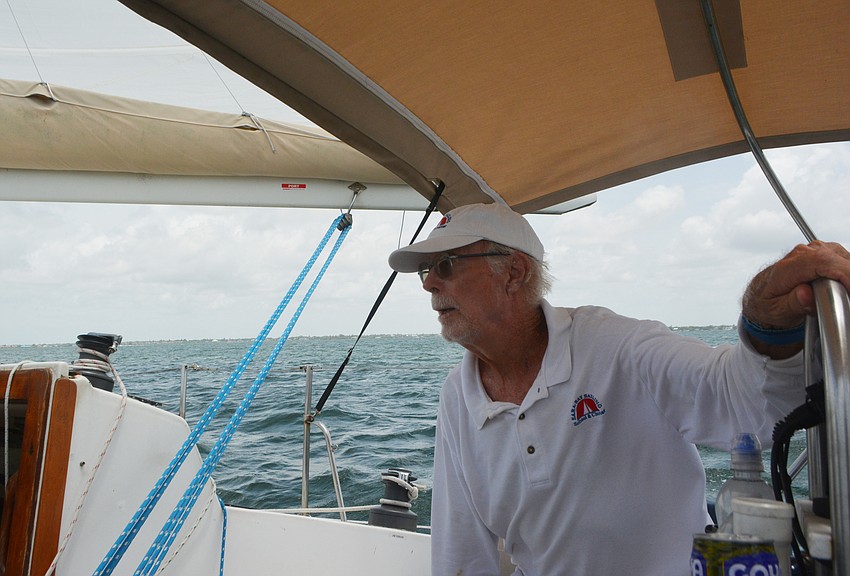

We’ve hardly left the dock for this intro to sailing lesson and already Sara-Bay Sailing School captains Bill Brooker, 76, and Charlie Schmitz, 77, are trading lighthearted pronouncements as we motor out into Sarasota Bay to find the breeze.

The boat is a Nightwind 35. National Sailing Hall of Fame member Bruce Kirby designed it. That probably means something to boat people. For the rest of us? There’s a roomy cockpit for the current crew of two, plus captains. A mast with a furled sail towers some 45 feet above us. Below deck, the cabin is spacious enough to come complete with a head, or bathroom. That one’s easy enough to remember.

But then there’s halyard, tack, lift, luff and bearing. Ropes are lines and lines are sheets. And sheets all have names.

“Learning to sail is like learning a foreign language,” says Schmitz. “But there are no verbs to conjugate!”

Originally from New Jersey, he delivers lines, the comedic kind, with a veteran entertainer’s sense of timing.

Brooker laughs, “Driving a car is more complicated.”

Before we climbed aboard this morning, we spent a few minutes in the school’s office in the Harbour Square building, which is styled like a Mediterranean villa — terracotta shingles, a sun-filled atrium lined with commercial offices. Schmitz showed us the American Sailing Association 101 course textbook. For someone who’s lived a life in landlocked states, the text is dense as calculus.

“You don’t have to memorize the book (before class),” said Schmitz. “What you need to know, I’m going to show you.”

This is a hands-on learning process, the captains explained. And the sooner it starts on the water, the better for students. Brooker knows from experience. He founded the Sara-Bay Sailing School and Charter in 2001, and since then his school has trained more than 5,000 sailors. Some have flown into Sarasota just to take the school's courses.

During COVID, business exploded, and the school saw three times as many students as it normally does. “We couldn’t even keep up with it,” said Brooker.

Over two full days, Sara-Bay Sailing can teach students everything they need to know to pass the ASA 101 course. Passing the 100-question test earns graduates a certification that effectively states they are able to sail in familiar waters and moderate winds. The class is also the first in a series of courses for U.S. sailors who would like to earn an International Proficiency Certificate. An IPC is a requirement to charter a sailboat in most European and Mediterranean waters.

Schmitz has been an instructor at Sara-Bay for seven years and has taught sailing for 15. He has only failed one student in that time. But she was a reluctant student from the get-go, only there at the behest of a significant other, Schmitz explained.

The clientele varies, but is mostly husband and wife teams, sailors needing those certifications, and first-timers. Sara-Bay focuses on adult learners, but has sometimes taught families with children. The age of students has ranged from 8 to 87. Which seems fitting for a school that’s open “24/7/365.25,” as Brooker put it.

The majority of Sara-Bay’s students start from “zero,” said Brooker. Even boat owners.

“You’d be surprised by how many people buy the boat before learning how to sail,” Brooker said.

Brooker has seen most challenges sailing can present, especially in Sarasota’s shallow waters. He started sailing when he was 14 years old. He began sailing around Sarasota in 1975 and became an instructor in 1995.

But even for a student of psychology, teaching sailing can present a unique challenge. Namely, husbands and wives who try to commandeer the lessons.

“It goes both ways,” said Brooker. "But there can be only one instructor on the boat."

“You can’t teach your wife or kids how to sail,” said Schmitz. “When it’s somebody close you take it personal.”

But aside from occasional family friction, “We seldom get grumpy people,” he added.

“Do you know what the most dangerous part of learning to sail is?” Brooker asked. “It’s the drive to the school.”

We’re far enough from shore to shut off the motor. The Key’s big houses, some vast as palaces, no longer interrupt the wind. We raise the mainsail (Brooker does most of the work).

“The three most important things to keep in mind while sailing?” the captains ask.

“What?” the two students reply.

“The wind, the wind, the wind.”

The sail hangs slack, a few ripples of wind snake through it. We’re drifting rather than sailing. At the helm, we get another brief lesson on the points of sail, angles. You can’t sail directly into the wind. You need to be at least 45 degrees off the wind’s direction to go anywhere. We learn to look at the inside of the sail, from which telltales hang in lines of three, thin brightly colored ribbons whose fluttering or streaming signals to us amateurs how we’re doing with our steering (poorly, so far).

With the sail slack, the boat feels sluggish and unwilling at the helm.

But then the sail fills with air. It looks like a white airplane wing. We take turns at the helm. It’s still like driving a bus but inputs lead to faster results. Hold the course, say the captains.

“Hold” makes it sound simple. But every moment requires constant adjustment and delicate inputs on the wheel to keep the boat headed true as it skims through an inconstant bay. Boat wakes, waves, changes in the breeze.

Lift, the principle that keeps pilots aloft, is the key, explains Brooker.

At 7 or 8 knots (8-9 mph) we’re going no faster than a cyclist. But it’s hard to pay attention now. Behind the helm, you look up and study cloth and canvas, as ancient Egyptians and Greeks did before you. Five thousand years — the theory has evolved, but the essence remains the same, along with its simple soundtrack: wind, rigging, water.

“It is aerobic. It is a sport. But the big essence we try to instill in people is that this is fun. (Our goal is) make it fun for people,” says Brooker.

Sara-Bay has taught people starting from zero. Two of them sailed to Australia. It took them years, but not for lack of skill.

“You tell people you’re sailing, they ask where you’re going,” says Brooker. “Sailing? You’re already there.”

The trip ends before we reach the dock. Schmitz turns on the engines to navigate through the buoys that lead back to Sara-Bay Sailing School. It’s easier to steer now, with the motors rumbling beneath us. But we’re no longer “there.” We’re going somewhere and in utilitarian fashion.

Pilots, doctors, lawyers, execs — Brooker mentions this segment of his clientele because they all have something in common. They find something on sailboats that they can’t find on land. Peace.

At least until it’s time to return home. Docking can be anxiety-producing, even for people who know what they’re doing, Brooker says. But the two captains are confident, even with an amateur helmsman at the wheel. Through the corridor of buoys, Brooker and Schmitz give a few simple directions — to mind this channel marker or that one.

“If you’re not bored to death docking, then you’re going too fast,” the captains say.

The two captains laugh, trading short stories of various sailors’ marina mishaps. Brooker and Schmitz take over on the final approach, backing the boat gently into position alongside the school’s dock.

I didn’t dock the boat then. I haven’t docked one before or since. It’s been weeks since I sailed with Sara-Bay, but I haven’t forgotten the advice, delivered with a punchline. It could be weeks, months or even years before I dock a sailboat, but I’ll remember to make sure I’m bored doing it.