- July 9, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

Native Floridians who mourn the loss of “Old Florida” aren’t always being purely sentimental.

The Sunshine State really was filled with magic places back in the day — and our region had plenty of magic, especially on the barrier islands. Our keys were packed with legendary hotels, restaurants, markets and gathering spots.

But legends, by definition, exist in the past. Most of these island delights have been demolished; a few have been repurposed. Either way, they’re gone. And, as Joni Mitchell reminds us, “You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone.”

I know these local legends are history. But here are a few of my favorites.

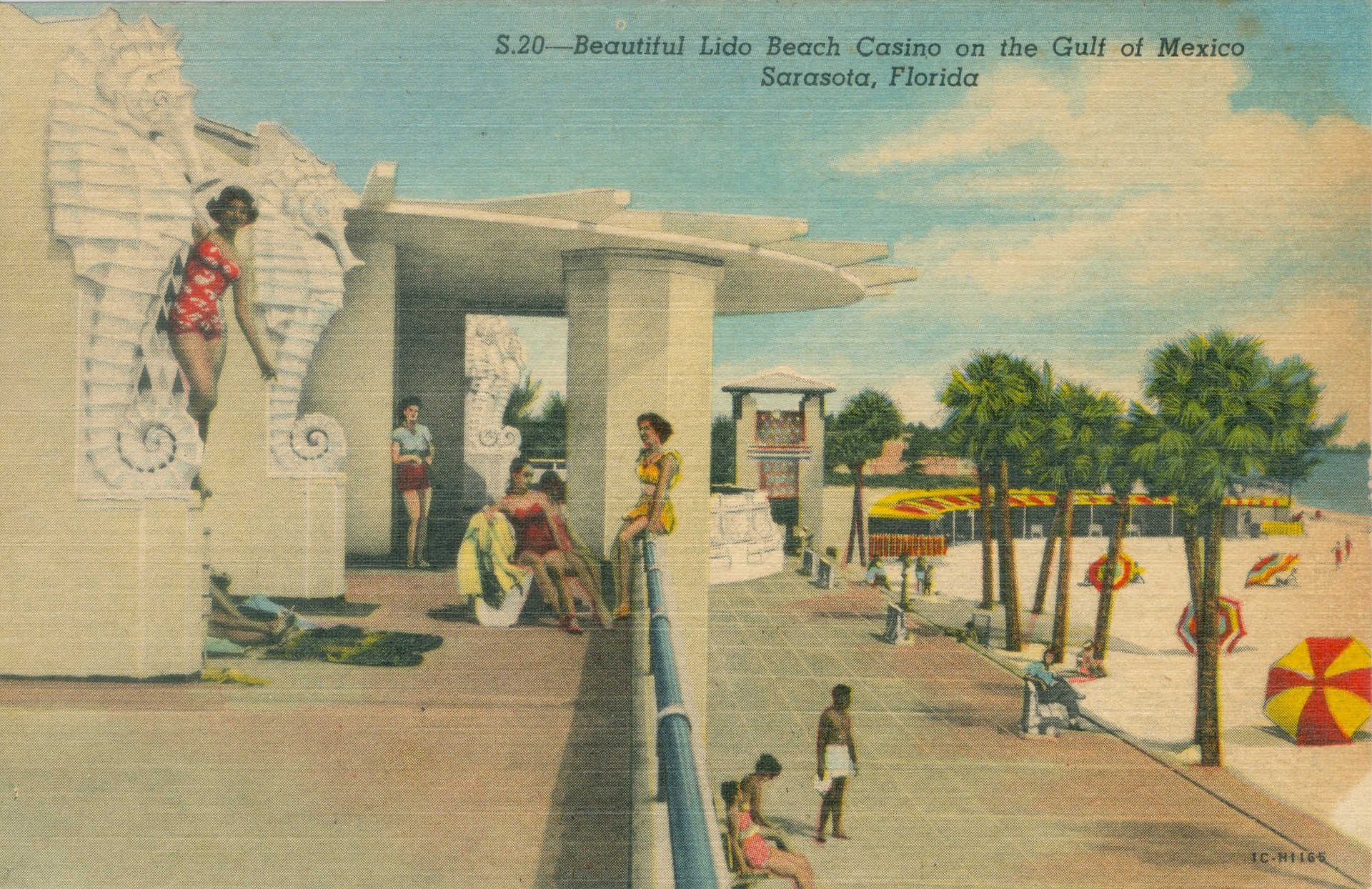

The Lido Casino. The Depression wasn’t always depressing for architectural dreamers. Along with creating jobs for working class heroes, the Works Projects Administration also subsidized playwrights, authors, artists — and architects such as Ralph Twitchell.

It commissioned him to design the Lido Casino in 1938. Twitchell’s Art Deco palace became a reality in 1940 and an instant hit with locals and tourists.

And why not? The casino sported a junior Olympic-sized pool with a high-diving board, curvy cabanas, bulging balconies, massive seahorse sculptures and glass block windows. (Thanks to a clever tilt, the glass lozenges looked like diamonds.) The casino’s interior was a trippy maze of mysterious stairways, boutiques, restaurants and a ballroom that closed in the 1960s.

As a kid, I pressed my nose to the diamond glass and wondered what the music used to sound like. As a teen, I drove to the casino with my friends one Saturday in 1969 — and saw a pile of debris where it used to stand. No more seahorses; no more glass diamonds; no more fantasy; no more Lido Casino. After a decade of demolition by neglect, the city of Sarasota had secretly smashed it the night before. So it goes.

Historical photos are all that’s left now. They’re great but fall short of the reality. Imagine a beach casino in the Land of Oz. The Lido Casino looked a lot like that.

The Summerhouse Restaurant was a glorious glass house set in a tropical garden. Architect Carl Abbott’s structure blurred the boundary between nature and humanity with floor-to-ceiling glass. Those transparent walls revealed a jungle worthy of a Rousseau painting — a subtropical Eden of gold trees, jacarandas, magnolias, oaks and palms.

On this project, Abbott was both the architect and the landscape architect. He echoed nature’s living forms with the restaurant’s organic form.

Abbott’s 1975 design had a geometric logic, but it wasn’t predictable. Despite its glass skin, the Summerhouse didn’t seem like a lifeless, crystalline entity. It was more like a life form that had taken root and grown on the site.

As with every living thing, its shape seemed both inevitable and surprising. A floating stairway led to the Tree Top Lounge on the balcony — and a bird’s-eye view of palm fronds reaching for the sky. Like leaves on a tree, the building’s wings flowed from the same pattern without exactly repeating it.

Great architecture aside, the Summerhouse became the go-to spot for swanky nights out and al fresco brunches in the gardens. In 2007, the developers of the Summer Cove condominiums bought both site and structure. Instead of tearing it down, the new owners turned the former restaurant into a private clubhouse. They still work hard to create community access and honor Abbott’s architectural legacy.

His masterpiece isn’t a restaurant anymore. But I’m glad it’s still here.

The Siesta Key Fish Market didn’t try to be pretty.

It was, in its essence, a rickety shack that Lonnie Blount opened as a fish market in 1932. There used to be thousands of fish markets just like it on Florida’s islands and shorelines. This one was a bustling gathering spot where folks from all backgrounds came to buy flopping fresh fish and share fish tales. (Legend has it that Eleanor Roosevelt was one of its customers.)

Blunt sold it in the ’50s, and it continued to thrive under the new owners. By the time Guy Asbury purchased it in 1993, the times were changing. Price tags for waterfront homes shot through the stratosphere on the key, and eventually, the city changed the zoning to residential only. SKFM was nestled on a secluded bayou at the north of Siesta Key — a sweet spot for developers, who built a new neighborhood in the blink of an eye.

By the mid-1990s, Asbury’s little shop of fishes was surrounded by upscale residences. True to form, his new neighbors didn’t want to live next to a fish market, despite its landmark status. When their barrage of complaints didn’t kill SKFM, they shifted to legal attacks and bombarded the market with constant injunctions, court orders, and citations for code and noise violations. For Asbury, it was the death of a thousand cuts. He didn’t give in. But his operating license had been grandfathered in.

In 1999, the city of Sarasota refused to renew it — and that’s how this story ends.

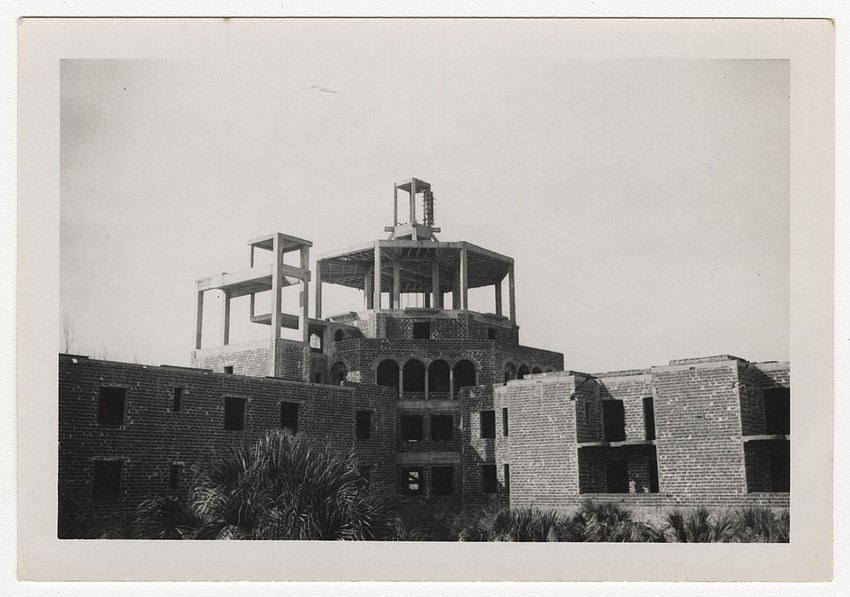

That Other Ritz-Carlton. John Ringling had many success stories as a developer. The Ritz-Carlton on Longboat Key wasn’t one of them.

At the dawn of the Jazz Age, Ringling had envisioned an opulent, 200-room resort hotel for the rich and famous. Work began in the mid-1920s at the fever-pitch height of the Florida land boom. Work stopped when that speculative fever broke. The boom went bust, and Ringling was hemorrhaging money. He sent all his workers home when the grand hotel was only half-done.

What they’d managed to build was an empty shell — crowned by the spidery steel framework of an unfinished cupola. Ringling vowed to finish the job, but thanks to the Great Depression, he never did. He couldn’t afford to complete his grand hotel or even tear it down.

After Ringling’s death, the Ritz’ skeletal structure remained a magnificent ruin for decades. The Arvida Corp. finally bought it — and got rid of it in 1964. The Longboat Key Club now stands on the site of Ringling’s demolished dream.

The Colony Beach & Tennis Resort once seemed like an eternal landmark in the middle of Longboat Key.

Developer Herb Field launched the resort in 1952. In the early years, The Colony’s hotel guests checked into rustic beach cottages. Nothing fancy. But celebrities and jet-setting travelers fell in love with the place. Their love affair extended to Longboat Key — and helped make it a global tourist destination.

Murray “Murf” Klauber purchased the property in 1970 and reinvented it as a four-star tennis resort. In its heyday, the nearly 18-acre resort boasted 237 condominium units, three restaurants, a gourmet market, a tennis boutique and 21 tennis courts — along with a world-acclaimed tennis program led by Nick Bollettieri.

But despite its first-class status, The Colony never put on airs. The Monkey Bar offered incontrovertible proof of its egalitarian ethos. People from all walks of life hung out here, including artists, writers, politicos and celebs. (The actual simians were safely contained in a mural on the bar’s wall.) The Colony was sometimes referred to as Klauber’s private kingdom, and visitors clearly loved his kingdom’s relaxed vibe.

But as time passed, not all of The Colony’s condo owners felt the love. Guests. Owners. How do you keep them both happy? Serving two masters is notoriously difficult.

At The Colony, it ultimately proved to be impossible. In 2010, the resort closed its doors due to legal complications worthy of a Carl Hiaasen novel. Longboat Key got a little more respectable — and a little less fun.

The Buccaneer Inn sounds like a restaurant for pirates. Jolly idea, but nay.

’Twere more like a family restaurant what served up great steak or fishy fare with a side order of romantic pirate hokum. Mom and Dad could carve into their rare rib-eyes and exchange significant looks. Betimes their tots could dig their tiny fists into a sawdust-filled treasure chest — and pull up a glorious booty of chocolate doubloons and plastic ray guns. (As a kid, I had that experience and decided that eating out was fun.)

This Herb Field fellow, remember him from The Colony? Well, he were the restaurateur/developer who created this happy place in 1957. Fun had always been his idea of treasure. Arrr, but a new generation of developers had another definition and took Field’s rollicking restaurant off the map in 2005.

Now all the jolly pirates have been laid away to rest. And so has the Buccaneer Inn.