- April 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

“The fundamental (but recently forgotten) core mission of cities is to accelerate the upward social and economic mobility of its inhabitants.” –Joel Kotkin, Chapman University

Planners should maximize the extent to which people can plan their own lives.” –M. Nolan Gray, Author, “Arbitrary Lines”

Longboat Key residents — be they full or part time — are not likely to think or worry much about it, but the most pressing economic issue squeezing this region like a mean vice is the high cost of housing.

The adverse effects of this are being felt in everyday living throughout the region, and, as other regions have shown, they will only worsen in years to come. That is, unless policymakers and the public have the courage and goodwill for dramatic changes.

Surely, you have experienced the effects of high housing costs — and not just the price you paid for your home or condo. Here is one: You call your doctor for an appointment, and the automated answering voice apologizes and says the doctor’s office is short-staffed. That is the situation virtually everywhere.

At the same time, we hear story after story how the cost of housing has scared off job recruits from moving here. Business owners tell us how they hired candidates, only to lose them once the candidate tried to find affordable housing.

Talk to every business owner in this region, and she or he will tell you hiring skilled people is the number one challenge.

That critical shortage of skilled labor is a result of the shortage of affordable housing for the middle and starter classes of workers.

This imbalance certainly isn’t new. It has been a slow, tightening squeeze for two decades. But in the wake of the pandemic, the labor shortage and rising cost of housing have become especially acute.

They are especially exacerbated in destination resort-retirement communities similar to Greater Sarasota-Bradenton.

But these conditions are not just affecting Sarasota. Here is the reality: Florida is no longer an inexpensive place to live.

Just the opposite.

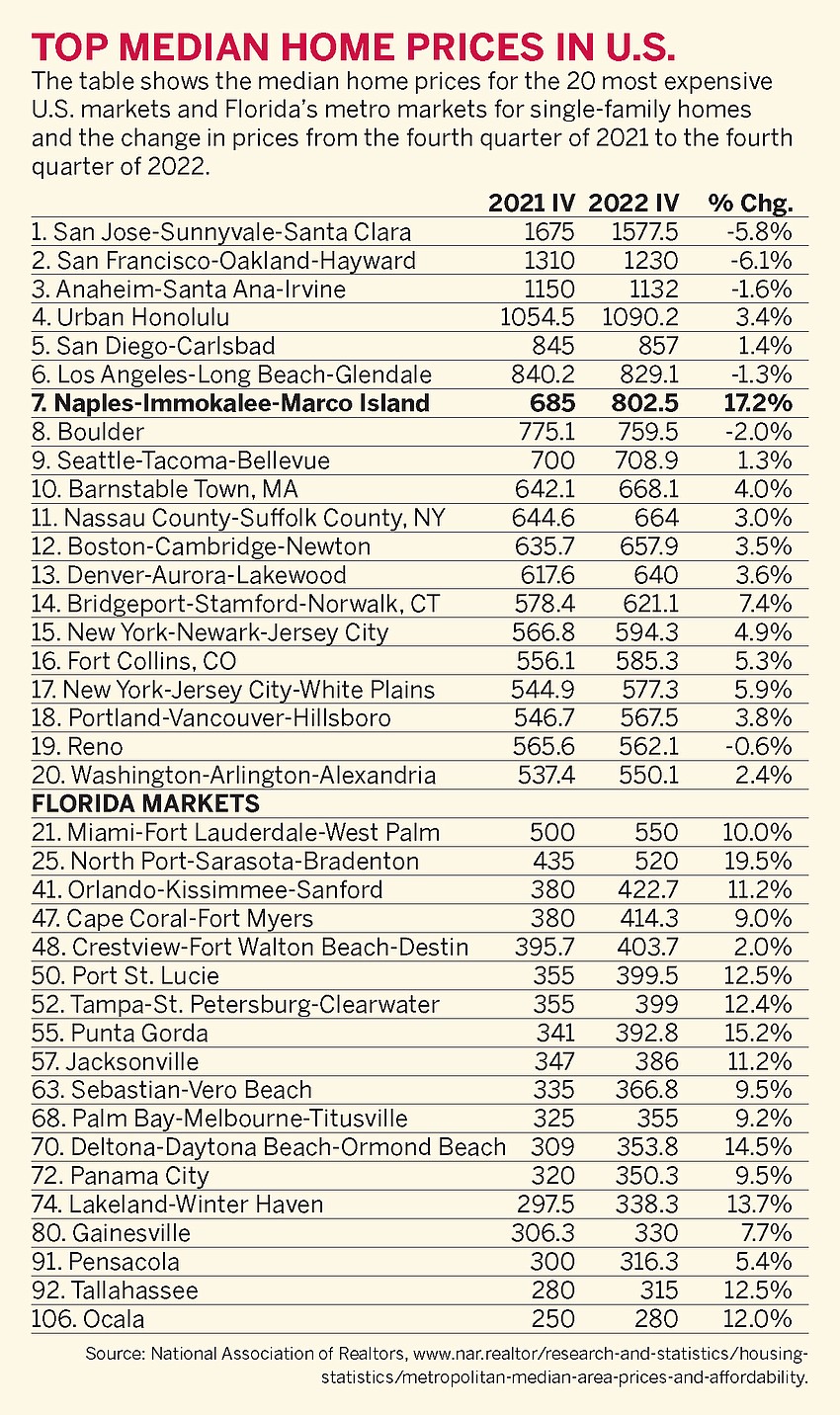

The accompanying table shows Florida has 18 of the 100 most expensive metro markets ranked by median sales prices for single-family homes. That is nearly 20% of the total, and it includes every metro market in Florida, except Ocala, which ranks 106th.

The cause of this is simple economics: Supply and demand. Florida’s population growth — a 50-year phenomenon — has outstripped the growth in supply.

But go a step further. When you look into “why” the supply has not kept up, that’s when the issue becomes more complicated. Multiple forces have restricted the supply.

One of the chief inhibitors is existing residents. Just as the sun rises in the east, throughout Florida, and especially in northern Sarasota County, the minute a developer proposes apartments anywhere or, say, a 100-home development in the suburbs, nearby neighbors show up at commission meetings in opposition.

To an extent, it’s understandable. Few people like their neighborhoods and streets to change (e.g. more people). You can also say it’s an economic benefit for existing residents to restrict supply. Look what that has done to the value of homes on Longboat Key.

Perhaps the biggest inhibitor to supply is at the governmental level. Over the decades, elected officials have adopted encyclopedias of zoning and development ordinances that make it near impossible to build starter homes that would allow a builder to make a profit.

It’s routine for developers to go through multiple public hearings with their lawyers, engineers and architects at their sides, each running the clock on their fees and driving up the cost of housing.

Add to that the myriad impact fees and other regulatory requirements, and the costs keep rising.

Two examples: minimum lot sizes and parking requirements. Allowing smaller lot sizes and fewer parking requirements would reduce land and planning costs dramatically. After Houston lowered minimum lot size requirements, it saw the construction of 25,000 new starter units around the city.

When the California Legislature legalized accessory dwelling units (e.g. garage apartments) in 2016, those units grew from almost none in 2016 to 10,000 in 2021.

These examples show there are multiple paths to incentivizing the development of more affordable housing. In fact, there is a new organization sweeping the country — YIMBY Action (Yes In My Back Yard), a national not-for-profit with local chapters working to change laws and incentives in ways that bring about more affordable housing for working people.

If there is a market ripe for this kind of effort, it is Greater Sarasota and the city of Sarasota in particular. (There is a YIMBY Tampa, YimbyTampa.com.)

Instead of addressing the question of what it can do to make it less costly to develop housing, Sarasota city commissioners are now seriously exploring becoming the developer and owners of below-market rate apartments. This is worse than the city thinking it can operate a golf course.

Suffice it to say, while it’s too late for Longboat Key ever to become a locale for more affordable housing, Longboat residents, and all Sarasota-Manatee residents, for that matter, have a financial and lifestyle stake in the region’s supply of housing.

Surely, everyone’s preference would be to have an economically flourishing region that offers great opportunities “for the upward social and economic mobility of its inhabitants.”