- July 9, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

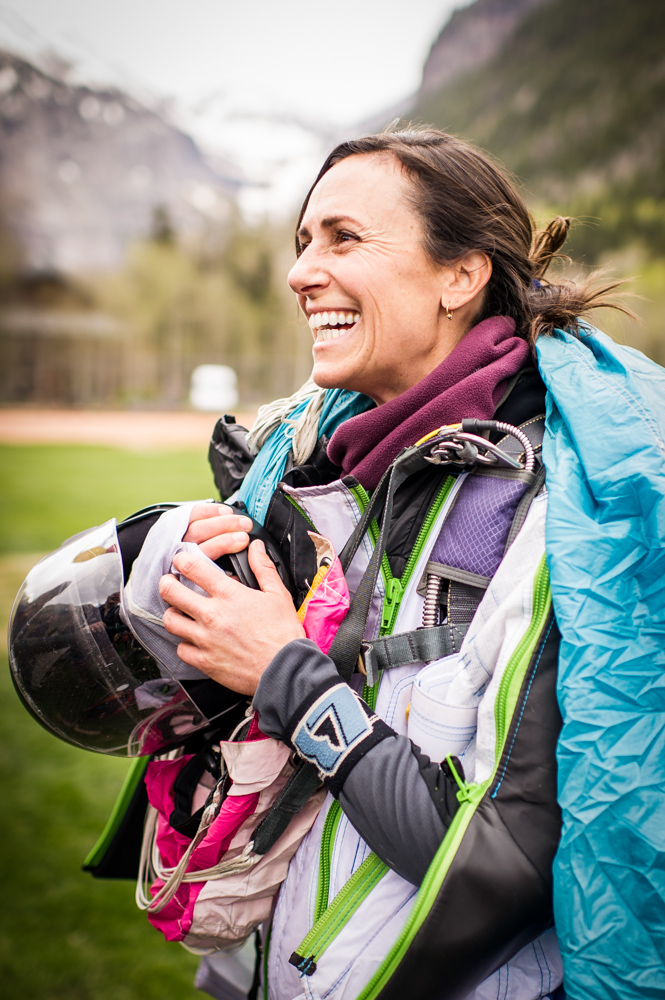

Steph Davis will always push forward.

It was one of the first lessons she learned as a burgeoning rock climber, on the side of Fitzroy mountain range in Patagonia, Argentina, in 1996. She was stuck 3,000 feet in the air, her tent suspended by ropes and battered by the elements: a raging, windy snowstorm that seemed like it would never die. She had already tried to wait out the storm for days at the mountain's base before beginning her climb, in hopes of clear skies, and she was low on food and the fuel used to melt the snow on the mountain into water. Things were dire.

Not wanting to risk her life any further, she turned around. Davis failed to climb any of Fitzroy's seven peaks on that trip. She was, in her own words, demoralized.

But she went back, again and again, until she became the first woman to summit all seven of them.

"The weather didn't get better (on those trips)," Davis, now 49, said. "The mountains didn't get easier. What changed was my mindset. I accepted that going forward might mean going sideways or even backwards for a while, because eventually I would get somewhere. The only thing that really mattered was the simple decision to start."

Davis shared the anecdote at a speaking event hosted by Stifel, a financial services firm, at The Ritz-Carlton, Sarasota, on Feb. 16.

Her talk had little to do with money. It had plenty to do with risk, something that Davis faces each time she starts a new extreme sports challenge. She's succeeded on many of them, often spectacularly so. In addition to her Patagonia feats, Davis was the second woman to free climb Yosemite National Park's El Capitan mountain in a day, and the first woman to free climb the mountain's notorious 3,000-foot Salathé Wall. She also BASE jumps, skydives and flies in a wingsuit in her free time, in case rock climbing wasn't thrilling enough. In 2017, Men's Journal named Davis one of the 25 most adventurous women of the past 25 years.

"It's a lot of balancing going on between them all the time," Davis said of her exploits after the event. "It makes it fun for me and keeps it fresh."

Davis was hooked from the first time she stepped foot on a mountain as a freshman at the University of Maryland, taking a day trip with a guy she randomly met to Carderock Park in Bethesda— a paltry climb compared to what she does now. But the experience was enough to hook her for life.

"It was a whole new world that I had not experienced before," Davis said. "Today, with social media, everybody sees everything all the time, but back then, it was this weird, unknown thing."

She quickly moved on to bigger mountains with higher levels of difficulty, and that's where the need to push forward — both physically and mentally — began. The risk of what Davis does is real. When Davis was stuck on the side of Fitzroy waiting out the snowstorm, she thought about climbers who had died during the attempt, one of whom's frozen body remained close to where she sat; no one was able to retrieve it. In 2013, Davis' second husband, Mario Richard, died during a wingsuit jump in Italy. No matter how much preparation someone has, one slip or absent-minded mistake can turn into tragedy. Moving on from Richard's accident was the hardest thing she's had to do, Davis said.

Still, she persists, because it's all she knows how to do.

"My parents (Virgil Davis and Connie Davis) have struggled with it," Davis said. "It's been 30 years now, so they have slowly gotten used to it, but they still have some concerns. And at the beginning it was, 'This whole thing is dangerous. Where are you going all the time? You're in some foreign country and not getting a good job? What are you going to do?' It was extremely hard for them."

Davis spent many of her early climbing years living out of a hand-me-down Oldsmobile in Moab, Utah, training as much as she could while waiting tables for just enough money to afford food, beverages and a little bit of gear. Earlier, Davis worked as a teaching assistant for a small stipend while getting her master's degree in literature at Colorado State University. At all times she kept her overhead as low as possible, Davis said, and still does.

Thirty years later, Davis has indeed made it work, but she's not one to look back on her accomplishments satisfied, or at all. Davis married her third husband, skydiving instructor Ian Mitchard, in November 2018, and she said Mitchard often encourages her to be happy with what she's done.

Davis, a self-professed perfectionist, is not, usually reflecting on her deeds with little more than a shrug, or pivoting to thoughts about a new challenge that hasn't gone as well as she would like.

"I think having an analytic and evaluation-based approach is important for safety, success and achievement," Davis said. "But it also can be hard to get excited about yourself. There's more humility than there is self-congratulation."

Eventually, the push forward will stop, either by choice or by the forces of nature. Davis said she knows that one day, she will no longer have the skill she once did, and that fact may increase the risk to a point where it no longer makes sense to continue. But she's been saying variations on "This won't last" for 30 years. It's now 2023, and she's still going. Davis said she feels as capable as she ever has.

Until that changes, saying "enough" won't even enter her mind.

"I hear people say, 'Oh, I'm injured, and it's because I'm getting older,'" Davis said. "But you got injured 30 years ago, too. That's part of being an athlete. Why does it (being older) mean you can't get better? It doesn't make any sense.

"We get into this mentality and I don't think it's the right way to look at it. Maybe, physically, we can continue to take care of ourselves and improve. It seems like that so far, for me."