- June 1, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

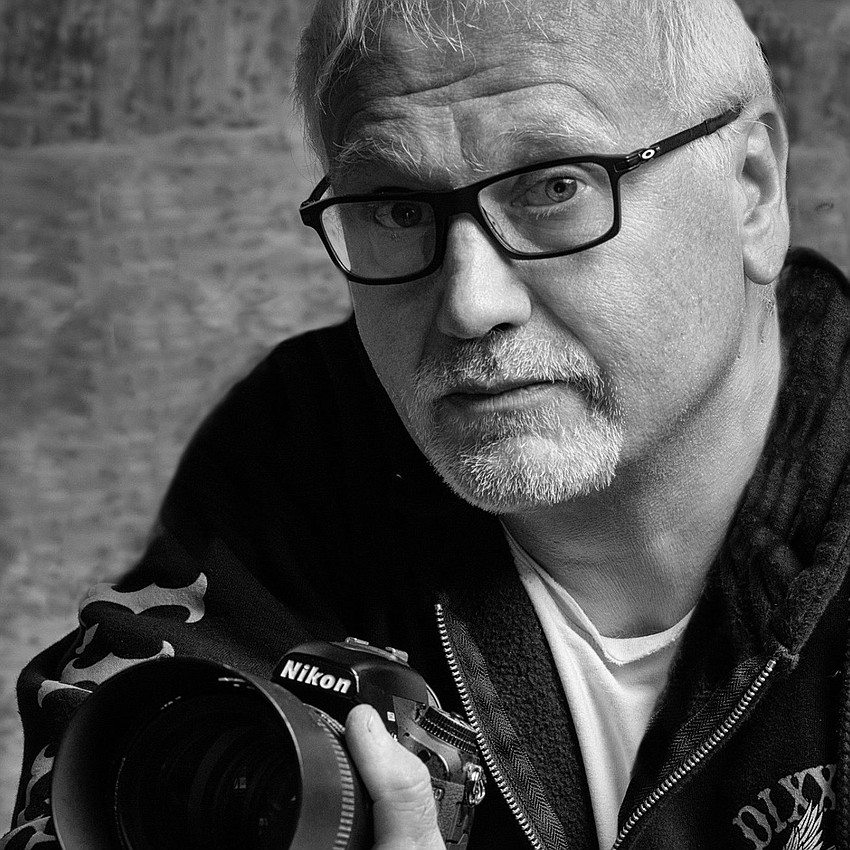

Allan Mestel says his wife describes him as a housebound feral cat.

Without a new project or destination, "I start tearing up the furniture and scratching at the windows,” he joked.

But Mestel is doing serious work, and the places he goes are often dangerous. The former TV commercial director is now a freelance human rights photographer in his spare time.

He was in Minneapolis after George Floyd’s death and during Derek Chauvin’s trial. He flew to Uvalde, Texas, after the May 2022 mass shooting at an elementary school. He’s been on both sides of the border between the United States and Mexico photographing migrants.

And he’s been to Ukraine twice since the Russian invasion in February 2022. Mestel’s photographs have won awards and been featured in the New York Times, on CNN and in an NBC documentary. He recently shared some photographs with the Longboat Observer and sat down to recount his travels along the border and inside the country.

Mestel and his wife Robyne own Beach Fitness in Whitney Plaza. He says he always had a passion for human rights and photography. By 10, he’d already converted his grandmother’s hall closet into a dark room. Photography remained a hobby throughout his life, but it didn’t become a focus until he left the advertising business behind.

In 2014, the couple moved from Toronto, Canada to Bradenton and opened up shop on the north end of Longboat Key. With Robyne spearheading the gym, Mestel opened a photography studio a few doors down. The portrait studio stayed in the plaza for three years, but has since relocated to Florida Boulevard in Bradenton.

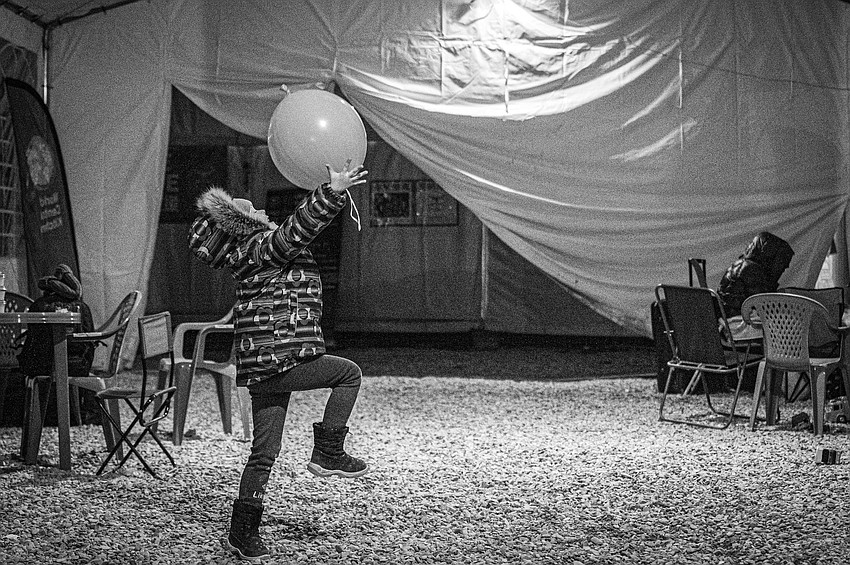

With a supportive wife holding down the fort for their two children, ages 10 and 13, Mestel flew to Krakow, Poland, only three weeks after the initial invasion to photograph the exodus of refugees.

In the style of street photography, those images capture the upheaval and uncertainty. Mestel’s photographs convey the toll of war through eyes and posture versus destruction and crowds.

But even a photo of a traffic jam has a story to tell. One, in particular, captures the kindness of strangers in the worst of times. The cars at a dead stop, the line stretches toward the horizon and around a curve. None of them are public buses or army transport vehicles, the drivers are regular Joe’s from surrounding countries offering their help.

They used their own cars and rented buses, traveling for days to reach the border. At the front of the line, drivers stated what country they were returning to and the Polish military matched them with refugees who had relatives in that country. Passengers fled with one bag or whatever they could carry.

“The Polish army was getting them organized, getting people directly from the border, and almost immediately, they’d get clothed, they’d get fed,” Mestel said. “They’d get resources made available to them as they came across the border, but (the army) kept them moving from the border to other places, so they didn’t develop a backlog.”

Soldiers performed beyond their duties. One young soldier caught Mestel’s eye because he never saw her without a baby. The babies would change, but her arms never stopped rocking. That too is essential work during wartime.

Mestel didn’t cross the border into Ukraine during his first trip. In July, he did. The first and last sounds he heard upon entering and leaving the country were air raid alerts. He heard that sound every day for three weeks, but the visual that most struck him was the blue and yellow Ukrainian flag.

“(The Russians) are doing their best to simply demoralize them. They’ve got all these destroyed buildings, but they’re not being demoralized,” he said. “You see the Ukrainian flag everywhere.”

A few days after photographing a Ukrainian air force monument in the town center of Vinnytsia, the city was destroyed by cruise missiles. Mestel was in Odessa by then, where he says he was only “semi-arrested and interrogated.”

“By the time it was all over, the guy shook my hand,” he said, “But some guy photographing a police station that’s fortified, it could be anyone.”

The fear was that he was photographing a target for a future attack. Outside of a few close calls, Mestel got lucky. Although this time around, there was more destruction than people to photograph. If he saw people on the streets, they weren’t walking. They were hurrying to get back off the streets.

Mestel visited a hospital in Serhiivka, where he met a group of 20-somethings disfigured from shrapnel. They were attending a graduation party when the hotel was struck by a bomb. They were lucky too. Not all their friends survived.

“This is not collateral damage on a military target,” Mestel said. “What you have is the Russians waging an illegal, strategic war on the civilian population of Ukraine, and the Ukrainians are not reciprocating. The Ukrainians are just defending their territory by fighting the invading army.”

Mestel saw homes collapsed and civilian cars riddled by machine gun bullets. He saw “miha” spray painted on buildings where landmines were identified but not yet recovered by minesweepers. Yet the people make him want to return.

“I’d like to go back and use some of my contacts over there to get into some of the hospitals, rehabs and homes and focus on trying to present more human stories about the people who have been affected by this war.”